6. Barack Obama

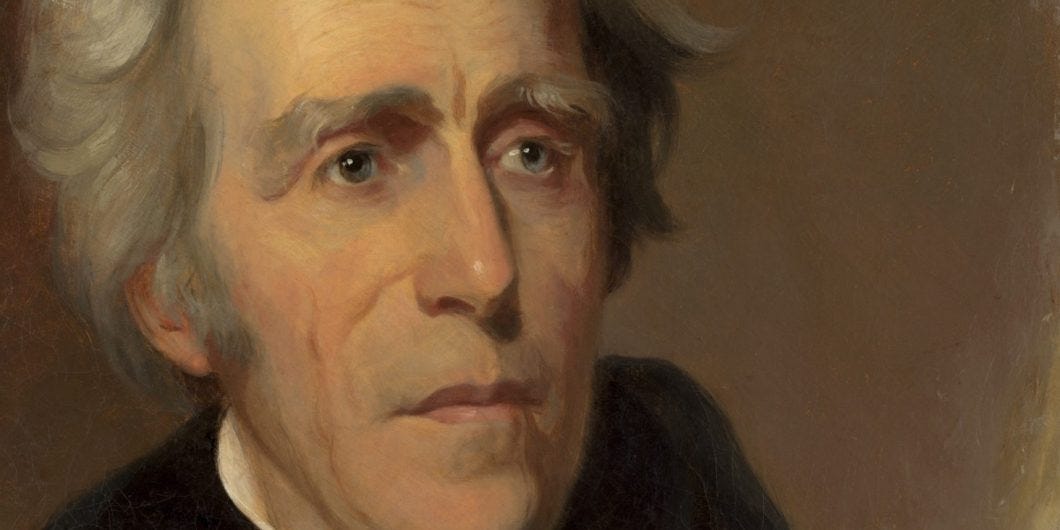

3. Andrew Jackson

After Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828, thousands of his supporters traveled to Washington to celebrate his inauguration. And to ensure his inauguration. They thought he should have been inaugurated four years earlier. His enemies had stolen the presidency from him, they believed. A cabal had conspired against him in the House of Representatives after no candidate won a majority of electors in the four-way race. The Jackson men didn't resist the crooked outcome, not by force at any rate. Instead they had mobilized at once and begun campaigning for the rematch. Having won that contest, they now wanted to make certain the prize wasn't stolen at the last minute.

They were a rough and rowdy group, mostly westerners from the region beyond the mountains. Simply getting to Washington in those days was no small feat. But some were Jackson's soldiers from long marches in the War of 1812, and a winter trip from Tennessee and Kentucky hardly daunted them.

They terrified Washington by their appearance. In the three decades since the national capital had moved to the new city on the Potomac, a genteel society had grown up there. Some of the residents had worked in government offices since the days of John Adams. Many thought of the government as their own. That Jackson had overthrown the son of John Adams, John Quincy Adams, was startling enough. The rumors that he was going to throw them all out of office made them shudder for their own futures.

The bearded, booted rabble who poured into the city appeared the shock troops of revolution. Since Jefferson, the White House had hosted levees for distinguished residents of Washington City and visitors to the capital. Jackson's team had announced a levee to follow his inauguration. The Washingtonians held their breath.

The post-inauguration reception was everything they feared. The barbarians arrived hungry and thirsty. They ate and drank and demanded more. They broke punch bowls and china. They tracked mud on the carpets and wiped their greasy hands on the drapes. When Jackson himself arrived, they surged toward their hero with an energy that caused Old Hickory, who had never retreated before British troops or hostile Indians, to flee for his life. He barely avoided the crush.

Washington was never the same again. Nor was the American presidency. Jackson rode a wave of democracy into the White House. His contemporaries called him “the people's president,” some appreciatively and some derisively. Ever since, the presidency has been the office of the American people. In the beginning, most presidential electors had been chosen by state legislatures, but by Jackson's day, nearly all states had handed that responsibility to the people. Moreover, restrictions on voting had diminished dramatically. By 1828, essentially all white adult males could vote. America had become a democracy.

Jackson was the first poor boy to reach the White House. His predecessors had advantages of wealth, education and connection he lacked. Ordinary Americans loved him because he was one of them. Not all his successors shared his humble origins, but all had to act as though they did. Successful presidents had to display a common touch. If they didn't come by it naturally, they had to fake it.

Jackson's enemies despised him as much as his supporters loved him. A new political party emerged, originally calling themselves Anti-Jacksonians, later Whigs. Their leader, Henry Clay, tried to trap Jackson into either approving a renewal of the charter of the Bank of the United States, which Clay and his moneyed friends favored, or vetoing the renewal and going down to defeat by Clay in 1832.

Jackson understood the spirit of the country in the age of democracy better than Clay did. He vetoed the bank and let Clay be damned. Voters stood by him and resoundingly returned him to office.

Even after he went home to the Hermitage in Tennessee at the end of his second term, he remained the most admired man in America. Mothers and fathers named their baby boys Andrew Jackson Smith, Andrew Jackson Jones, Andrew Jackson Turner. To this day, more geographic features in the United States are named for Andrew Jackson—Jackson County, Jacksonville, Lake Jackson—than for any other individual.

Toward the end of the 20th century, Jackson's popularity faded. Like some other historic figures, he became a victim of his own success. What his contemporaries valued him for, in Jackson's case democracy, their distant descendants took for granted. What those later generations held against Jackson, especially his stern policy toward Indians, was considered a venial sin by his contemporaries, if a sin at all.

Success in the politics of democracy requires popularity in one's own time. No president was ever more popular in his own time than Jackson. He was content to accept this and let posterity be damned.

"What those later generations held against Jackson, especially his stern policy toward Indians . . ." "Stern" is hardly the word I'd use. Today we'd call it ethnic cleansing. A couple of decades ago, I was chatting at a conference with someone from the Cherokee tribe. He said some Indian activists refuse to accept $20 bills because of Old Hickory's portrait on it.

His Presidency sparked an eternal war between the elites and the common people which continues to persist in America to this day.