“Sir,” wrote James Neelly to Thomas Jefferson on Oct. 18, 1809 from Nashville: “It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis, Governor of Upper Louisiana, who died on the Morning of the 11th Instant, and I am Sorry to Say by Suicide.”

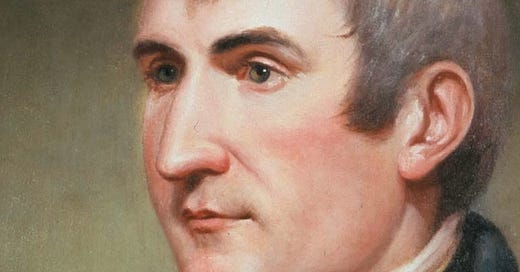

Jefferson was disturbed to hear of Lewis’s death, but he wasn’t surprised. Lewis was a native of Jefferson’s own Albemarle County in Virginia, and after military field service he had been appointed Jefferson’s private secretary. Lewis lived in the White House during Jefferson’s first term and impressed his boss sufficiently that when the president needed an officer to command an expedition to explore the newly purchased Louisiana territory, he selected Lewis.

Jefferson saw talent in Lewis but he also saw turmoil. “He was much afflicted and habitually so with hypochondria,” Jefferson wrote to an army comrade of Lewis. Hypochondria was then a generic term for anxiety disorder. “This was probably increased by the habit into which he had fallen and the painful reflections that would necessarily produce in a mind like his.” Lewis seems to have become dependent on opiates or alcohol. “His loss to the world is a very great one.”

It was especially great, in Jefferson’s view, in that Lewis was on his way from St. Louis to Washington to oversee publication of his journal of the expedition he and William Clark had headed, which had not merely explored the Louisiana territory but pushed all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

James Neelly elaborated on what he had learned of Lewis’s last weeks and days. “I arrived at the Chickasaw Bluffs”—near Memphis—“on or about the 18th of September, where I found the Governor (who had reached there two days before me from St. Louis) in very bad health. It appears that his first intention was to go around by water to the City of Washington; but his thinking a war with England probable, and that his valuable papers might be in danger of falling into the hands of the British, he was thereby induced to change his route.”

Lewis rode overland from the Mississippi to the Natchez Trace, a historic trail from Natchez to Nashville, and followed it toward the latter. He stopped for the night at the home of a man named Grinder, who took in travelers. Grinder was away, and his wife—“discovering the Governor to be deranged,” as Neelly heard from her—gave Lewis the house and slept in an adjacent building. “The woman reports that about three o’clock she heard two pistols fire off in the Governor’s room.” Mrs. Grinder woke the servants, who forced opened the door of Lewis’s room. “He had shot himself in the head with one pistol and a little below the breast with the other.” Lewis was still alive but barely. The loss of blood had made him thirsty. He asked for water and was given some. “He survived but a short time.”

Jefferson accepted the story. So did various other people who knew Lewis. Like Jefferson they had seen evidence of emotional distress. Some knew of financial difficulties Lewis had had with Congress regarding reimbursement for expenses he had incurred as territorial governor. Amid an economic depression brought on by Jefferson’s Embargo Act, which had the aim of compelling the British and the French to stop seizing American merchant ships during the lengthy war between the two European powers, Congress was cutting all expenditures it could. Lewis got shortchanged, leaving him to deal with merchants he had paid out of his own pocket. Congress and his creditors impugned his integrity, increasing his anxiety the more.

But others objected that Lewis wouldn’t have committed suicide, or at least hadn’t. A man who had stood up to Indians, grizzly bears, hunger and exposure en route to the Pacific dying by his own hand? It seemed improbable to many who knew Lewis as a hero. Suicide in those days was often viewed as demonstrating flawed character; members of Lewis’s family rejected the suicide assertion out of loyalty to their kinsman.

The circumstances of Lewis’s death, as related by Mrs. Grinder to James Neelly, seemed odd. Lewis was a soldier trained in the use of weapons; at point blank range he couldn’t kill himself with a single shot?

But if Lewis hadn’t killed himself, someone had murdered him. Who had motive and opportunity? Some pointed a finger at his servant, a free black man named Pernier, who was traveling with him and who was owed back pay by Lewis. Perhaps Pernier killed Lewis and stole the wages owed.

Except that Pernier didn’t act guilty. Nor did he show signs of having come into money. Instead he traveled on to Virginia to try to collect from Jefferson what he was owed by Lewis.

Highwaymen plagued travelers on the Natchez Trace, which included lonely stretches of forest. But no robberies had been reported lately, and no one had seen anyone who looked suspicious near the Grinder place.

One convoluted explanation was that Lewis somehow had discovered that James Wilkinson, a distinguished army general and formerly governor of Louisiana Territory, was secretly a spy for Spain, and that Wilkinson had had him killed. Wilkinson did turn out to be a spy, but no evidence emerged that Lewis knew he was.

The alternative explanations never gained serious traction. But neither did they go away. Those who clung to them seemed devoted to a particular view of great men. Meriwether Lewis had done a glorious thing carrying the American flag to the Pacific. A man who did that couldn’t meet his end in a miserable and nearly botched suicide attempt. Could he?

I don't think he committed suicide based on the way he was shot. He was also determined to get the journals to DC and to get the money paid for expenses. It seems cut and dry as suicide until you start to did deeper. Thanks for the post

Given the treachery of Aaron Burr, including his murder of Alexander Hamilton, it seems plausible that he was involved in a plot with Wilkinson to murder Lewis.