The hardest words

"We lost"

"We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender,” said Winston Churchill in June 1940. Yet still Britain might lose, Churchill secretly told Franklin Roosevelt at the same time, to urge the sending of American ships to prevent a defeat.

Britain did not lose. But if it had lost, Churchill might not have accepted blame. Governments and politicians are adept at shifting blame. Britain lost the war of the American Revolution, but the government that negotiated the peace was a different government than the one that had commenced the war. Russia lost World War I, but Lenin and the Bolsheviks blamed the government of the czar, which they had overthrown. Germany also lost World War I, but Hitler and the Nazis rejected the idea of defeat, instead saying Germany had been betrayed by enemies within, notably Jews.

Losing occurs in many human activities besides war. In every change of a status quo, there are winners and losers. The losers often resist their fate as long as possible. Yet at some point they are compelled to acknowledge defeat. Andrew Carnegie's father was a textile worker in Scotland displaced by machines. He kept looking for work in his old trade but never found it. Finally his wife had to concede defeat for the family and move them all to America, where young Andy made a new start.

Most immigrants had experiences like the Carnegies’. People don't uproot themselves and their families without good reason, such as suffering substantial decline in their fortunes. They struggle to resist the change until they’re forced to acknowledge that the old ways have been lost and won't be returning.

American Indians had similar experiences following contact with whites. As long as the whites were few, they had little effect on the Indian status quo—with the important exception of the havoc wrought by introduced diseases. Even with their reduced numbers, tribes could expect to continue living much as before. But when the white population increased, it exerted pressure on the Indians. Most resisted the white advance for a time. But the pressure grew ever greater.

In 1830 Congress approved the Indian Removal Act, mandating that if eastern tribes wanted to continue to live under their own governments, they would have to relocate to the federal territory across the Mississippi. They would receive land there and assistance with moving. The Indians had to decide whether to accept the offer or fight it.

Most of the eastern tribes accepted, signing treaties and relocating. None were happy about the arrangement, but the accepters concluded that the old ways were lost and that wisdom lay in making the best they could of the new order of things.

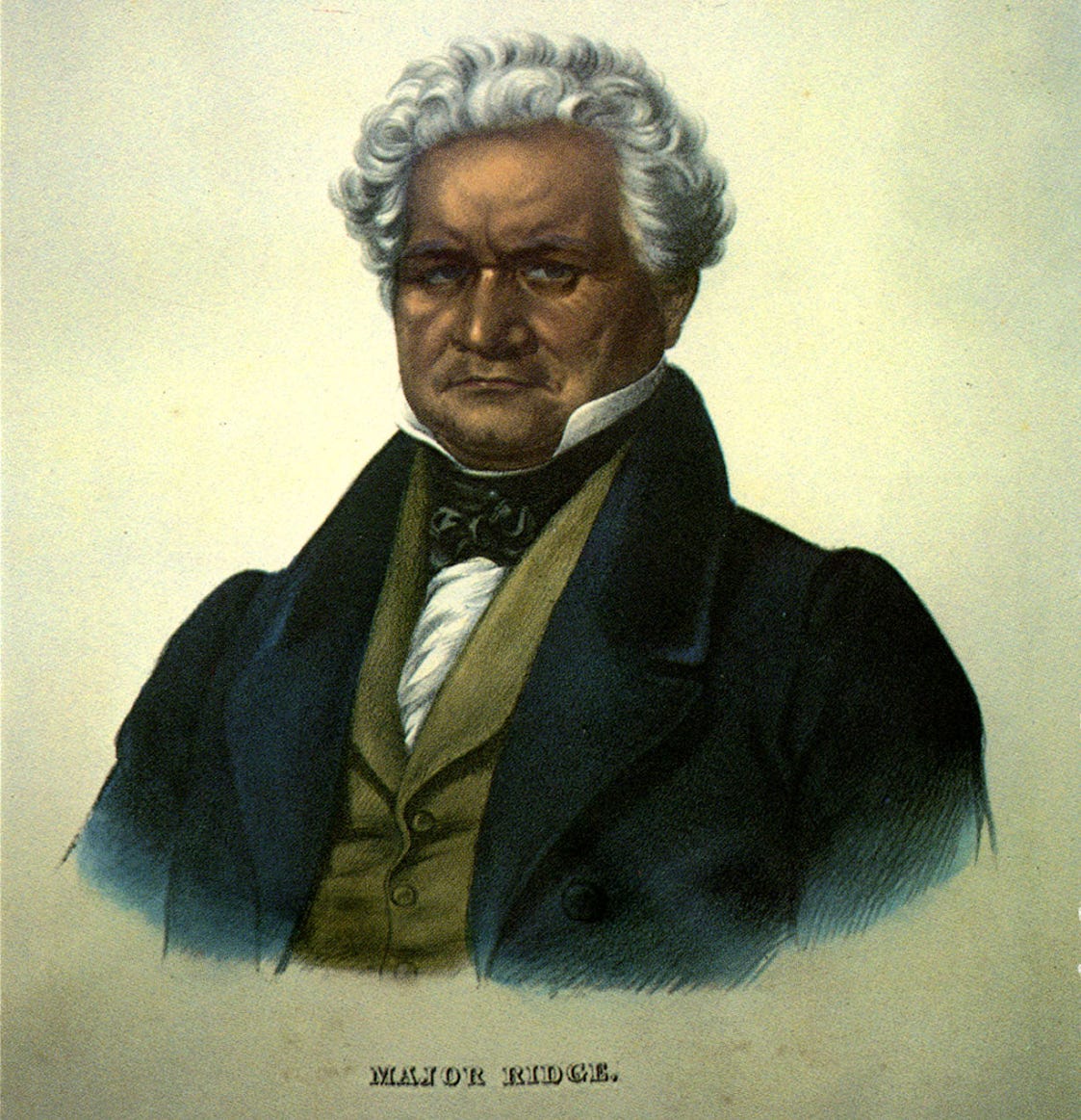

Some of the Cherokees accepted. A chief named Major Ridge and his followers signed a treaty at New Echota, Georgia, exchanging Cherokee lands in Georgia for land in what would become Oklahoma. They also received a promise of a payment of $5 million.

But a larger number of Cherokees, led by John Ross, rejected the New Echota treaty and denounced the Ridge men as traitors.

The Ridge group responded that the Ross men were leading the Cherokees to destruction. One way or another, they said, the white government was going to drive the Cherokees out of Georgia. Better for the Cherokees to leave under their own power than at the points of army bayonets.

The Ridge group left Georgia and arrived safely in Oklahoma. The Ross group stayed in Georgia until the bayonets came. Their forced march west was a disaster. In the rain and snow of winter, the migrants fell ill and died by the thousands. The “trail of tears” became seared in Cherokee consciousness.

The experience triggered a civil war among the Cherokees that lasted decades. Among the first casualties were Ridge and several of his lieutenants, assassinated by elements of the Ross group. The survivors among the Ridge party blamed Ross not only for the murders but for the deaths of the thousands on the trail, sacrificed to Ross's delusional stubbornness.

The question for the Cherokees, as for every tribe, was how long to keep fighting for what turned out to be a losing cause. The holdouts for the old ways elicited admiration for their bravery. But the bravery came at great cost to those they professed to be defending.

When to declare a losing cause lost? This question is at the heart of all kinds of decisions. At what point did the Vietnam war become a lost cause for the United States? What blame should be assigned to those leaders who kept America fighting beyond that point?

The intractable problem is that lost causes are never known to be such until they’re lost. Is a two-state solution between Israel and Palestine a lost cause? Or is it still worth fighting for? Is a Ukraine free of Russian troops a lost cause? How about an independent Taiwan?

We all deal with such questions at the personal level. Is this relationship worth fighting for? Or should I move on? Should I keep fighting for my dream career? Or should I switch to plan B? My cancer keeps coming back after each round of treatment, and the side effects of the treatment get worse and worse. Should I keep fighting, or accept that death is part of every life?

Reinhold Niebuhr, an American theologian, has been credited with a particular formulation of virtues germane to this basic human challenge: “God grant me serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Serenity and courage are praiseworthy traits. But wisdom is the operative one here, and the hardest to come by.

Another thought-provoking post, Bill. With the topic being lost causes, I’m surprised that you didn’t mention the state religion of the Lost Cause that emerged in the former Confederacy after the Civil War