Goodbye, Gutenberg

Don't bother to write

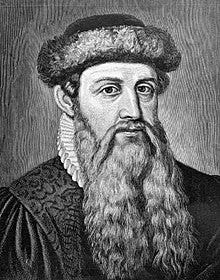

The age of general literacy began when Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in the 15th century. People had been reading and writing for thousands of years, but these readers and writers formed a small, privileged class. Books were expensive, being painstakingly transcribed by hand, and were available only to the wealthy. Before Gutenberg, stories intended for the general public were conveyed orally by poets or in plays. Think Homer and Aeschylus.

The printing press caused the price of books to plummet. For the first time, people of ordinary means could hope to lay hands on a book. This prospect gave them an incentive to learn to read. Popular democracy, which emerged in America and elsewhere in the 19th and 20th centuries, was both a cause and consequence of the spread of literacy. The egalitarianism implicit in democracy created demand for publicly funded schools; as people became educated, they sought additional rights. In 1810 scarcely 10 percent of the adults in the world could read. Two hundred years later that portion was nearly 90 percent.1

Yet by the middle of the 20th century new technologies were reducing the need for literacy. The great storytellers of the 19th century were novelists like Charles Dickens; the great storytellers of the 20th century were movie directors like John Ford and Steven Spielberg. In the 19th century, people got news and entertainment from newspapers and magazines; in the 20th century radio and television stole many of those readers and converted them into listeners and viewers. Meanwhile the telephone obviated much letter-writing.

Additional technologies accelerated the trend. Early computers were instructed by commands typed onto punch cards or on the keyboards of consoles. The Apple Macintosh, introduced in 1984, popularized the use of small images, or icons, as a way of issuing computer commands by the click of a mouse.

For some time before that, organizations catering to the visually impaired had tape-recorded books. Personal computers and smartphones broadened the market for audiobooks. By the early 21st century, there was hardly a book brought out by a major publisher that wasn't available in audio form. In cars, on sidewalks and on airplanes, people listened to books and magazines. And to podcasts, a medium that amounted to radio-on-demand.

The need for literacy continues to diminish. Of the major social media platforms, only Twitter is text-based. Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok are predominantly visual. People continue to send text messages and emails, but even these increasingly employ emojis and the like. Voice-recognition and -transcription software allows people to dictate texts and emails, and phones and computers to read them back orally.

These days a person who can’t read and write can live a fairly normal life. To be sure, it helps to be able to read a menu at a restaurant, a store sign on the street, the name of a movie on a theater marquee. But merely recognizing words is not the same as reading, and in those areas and many others, visual cues often suffice. People not facile in English have little difficulty ordering at McDonald's, telling a mattress store from a tire store, and finding their way to the right theater in a multiplex.

For decades to come, being able to read and write will continue to be essential in certain occupations. Lawyers and teachers aren't going to stop writing contracts and reading student papers. But mechanics don't have to read manuals anymore; videos have taken their place. Doctors notoriously never could write—legible prescriptions, at any rate; now they can dictate their notes. When Jimmy Carter was president, he was known for taking reams of memos and position papers upstairs to the White House residence each night. Donald Trump was a more effective communicator as president than Carter, and if he ever cracked a book or read a lengthy report, he kept the secret well. Presidents and other top executives can and often do gather information by being orally briefed. When Trump spoke, he made no literary allusions; indeed, the very non-literary character of his speaking style has been one of the keys to his success.

School children no longer learn cursive handwriting as a matter of course; many people today go weeks without picking up a pen. Much of the reading of material other than emails and text messages that continues to take place occurs in schools or on the job. Recreational reading is fighting a losing battle against video of one form or another, including video games.

Some lament the change, recalling the smell of book pages or the coziness of a favorite book store. But really, what's not to like about the return of human communication to its original oral form? Our brains are wired for that; children pick up language without even realizing they are doing so. Learning to read, by contrast, is a chore, comparatively simple for some but difficult or impossible for others. Before Gutenberg, readers constituted a kind of priesthood. As the need to read continues to diminish, some of the priests will remain, clinging to their letters the way Roman Catholic priests long clung to Latin.

The printed word or its digital equivalent will long be a repository for information. Reference books, scientific articles and legal documents are most useful in written form. After we stopped using scrolls, written works didn’t have to be read in order from start to finish; this is one advantage they have over the spoken word, and for some kinds of materials, this will keep them alive. Many people can read faster than others talk; when time is of the essence, such people will continue to choose reading over speech.

But time is often not of the essence. The message conveyed is not about information but about emotion and human interaction. The message tells a story. And in the realm of human stories, it's hard to beat the spoken word, the native language of us all.

https://ourworldindata.org/literacy

Another fine contribution from Prof. Brands on the state of literacy and in particular writing in our time.

Written language and linguistic structures expand our powers of representation into unbelievable limits to what we are capable of knowing. This symbolic power is the most mysterious of the ways we have of knowing because it opened a world of words and human culture. I don't think we will ever lose the written word. It gives us the time to ponder and exercise our imagination through the creations we construct with words. Poetry is a good example as we think about the work and the beautiful rhythms and choice of words and multiple meanings that the work can generate.

We may exist at some level without this means, but without it we limit our potential to grow.

I am one of those "can read faster than people speak." I get very frustrated when someone wants to send me "information" or "evidence" of something and it's a link to a Youtube video! UGH!

I do not lament the passing of cursive. It is of course the subject of intense debate. I see the pro-cursive side as presenting more of an emotional argument but trying to frame it scientifically. Humans have been reading "print" since Gutenberg! Then newspapers. I had a shop class in 8th grade for printing where we set type and made our own business cards. And now with computers, the need for it is unnecessary.

Cursive is a throwback to using quills which made cursive necessary. IMO cursive should be an optional class in schools right there with caligraphy, perhaps part of art class.