Burr and Trump

Law and politics

The indictment of former president Donald Trump on federal charges of mishandling classified documents and obstructing investigation breaks new ground in American political history. Richard Nixon came close to indictment while president for his role in the Watergate coverup, but the grand jury in the matter, questioning the constitutionality of criminal charges against a sitting president, branded him an “unindicted coconspirator,” postponing any prosecution until he left office. Gerald Ford nixed that by preemptively pardoning Nixon, after Nixon resigned and Ford took his place in the Oval Office.

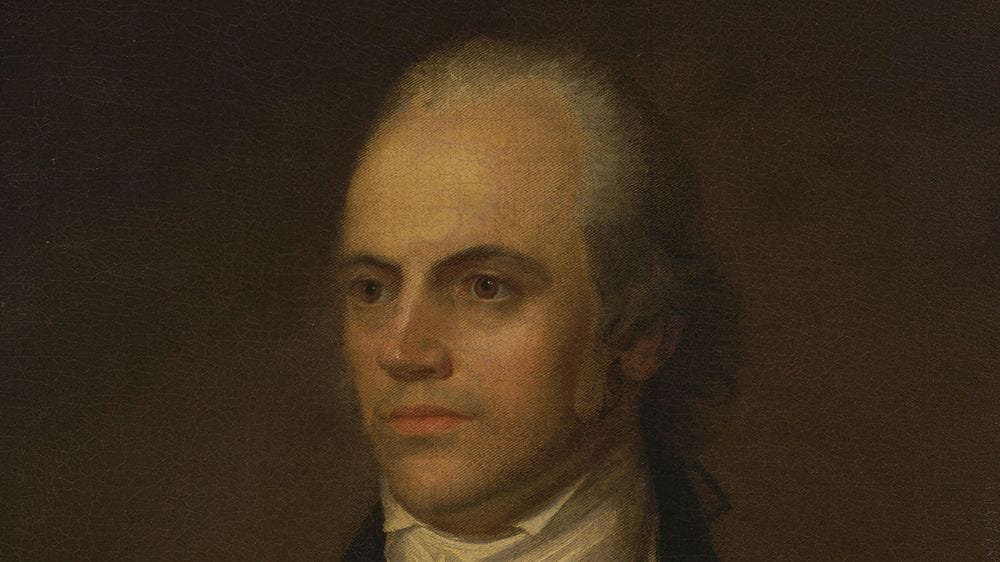

The closest historical parallel to Trump’s legal jeopardy is the prosecution of a former vice president, Aaron Burr, in 1807. Controversy stuck to Burr, the great rival at the New York bar and in New York politics of Alexander Hamilton. Against Hamilton’s and Hamilton’s Federalist allies, Burr delivered New York’s electors in the 1800 president race to the Republican ticket of Thomas Jefferson and himself. Hamilton responded by traducing Burr’s character when the electoral vote deadlocked and the contest went to the House of Representatives, which chose Jefferson over Burr (under the convoluted system in force at the time). Hamilton assailed Burr further when Burr ran for governor of New York in 1804, a race Burr lost. Burr accused Hamilton of crossing the line between politics and calumny; a duel resulted in which Hamilton was mortally wounded.

Dueling was illegal, and arrest warrants were issued in New Jersey, where the affair took place, and New York, where both duelists resided. Burr, still vice president, was shielded by his office, and as soon as his term ended he headed west, beyond the effective reach of the warrants. Westerners weren’t shocked by Burr’s killing of Hamilton; many of them had hated Hamilton for his monetary policies as treasury secretary, and more than a few were happy he’d died.

Burr meanwhile had fallen out with Jefferson, who elbowed his vice president aside as heir apparent in favor of Jefferson’s fellow Virginian James Madison. Jefferson chose to credit the nasty things Hamilton and the Federalists had said about Burr, and he kept an eye on his erstwhile partner. When Jefferson learned that Burr was outfitting an expedition of commerce and possibly more to the West, he concluded that treason was in the air. Many residents of the territory of Louisiana, the purchase of which was Jefferson’s great accomplishment as president, were restive under America rule, and Burr might lead them out of the Union.

Jefferson sent a message to Congress proclaiming Burr’s guilt as “beyond question.” He oversaw the calling of a federal grand jury in Kentucky to indict Burr. But Burr parried Jefferson by representing himself before the grand jury, which refused to indict. Indeed, residents of Frankfort hailed Burr as a hero and threw a grand fete in his honor.

Jefferson ordered Burr’s arrest anyway. Burr dodged for a time before surrendering. Another grand jury was summoned, in Mississippi Territory. It too refused to indict. Again Burr was celebrated, to Jefferson’s mounting frustration.

Jefferson sent the army after Burr, who surrendered again. He was transported to Richmond, Virginia, where, finally indicted, he stood trial.

The presiding judge was John Marshall. In those days justices of the Supreme Court rode circuit, and Marshall heard cases in Richmond, his home town. Marshall and Jefferson were kin but opposites in political and constitutional philosophy. Jefferson, a believer in small government, interpreted the Constitution narrowly. Marshall, a Federalist and friend of bigger government, interpreted it generously.

Except in the case of Aaron Burr, where Jefferson and Marshall swapped places on the ideological spectrum. The Constitution defines treason strictly: “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.”

The framers of the Constitution had reason for their strictness. In English history treason had been a catch-all charge employed by monarchs against their enemies; the framers wanted nothing like that for their new republic.

Jefferson, contradicting his own warnings against government overreach, threw the weight of the executive branch against Burr. Marshall, otherwise happy for government to employ its heft, held the prosecution and the jury to the letter of the law on treason.

Burr, again representing himself, kept pointing out the prosecution’s failure to produce a single witness, let alone the required two, to the overt act of war necessary for conviction. Marshall reminded the jury of this failure as he sent them to deliberate, and the jury delivered a verdict of not guilty.

The Burr acquittal proved a landmark in American legal history. Jefferson, after the manner of monarchs he professed to despise, had attempted to use treason as a political tool, and the court in the Burr case slapped him down. Treason trials have since been rare in America. The large majority of convictions have involved explicit collaboration with the enemy during war, especially World War II. The most celebrated treason conviction in American history, of abolitionist John Brown, was for treason against Virginia rather than the United States.

What does all this mean for Donald Trump? Nothing directly. The Burr trial happened long ago, and jurisprudence has evolved since then. But two aspects of the case are instructive.

First, Jefferson’s ham-fisted approach almost certainly weakened his cause. It raised the hackles of Marshall, who for the moment was reborn as a strict constructionist. President Joe Biden has kept his distance from Trump case; he would be well advised to continue to do so.

Second, although politics informs the rhetoric around high-profile trials, the law remains the law. Whatever Burr intended for his western expedition—an issue historians still debate—the prosecution failed to produce the witnesses required by the Constitution. Partisans today are rooting for and against a Trump conviction. But if the Burr case is any guide, the jury will deliver a verdict on the merits.

Which, like the outcome in the Burr case, will be the best result for the country.

(A version of this essay appeared in The Messenger on June 14, 2023.)

Perhaps a subject for a future essay

*Hamilton was mortally wounded