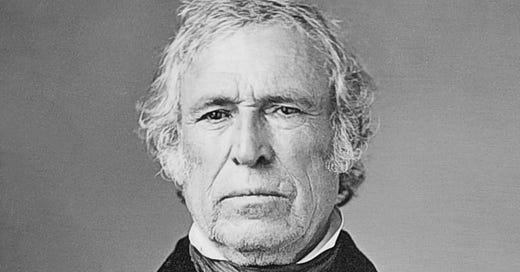

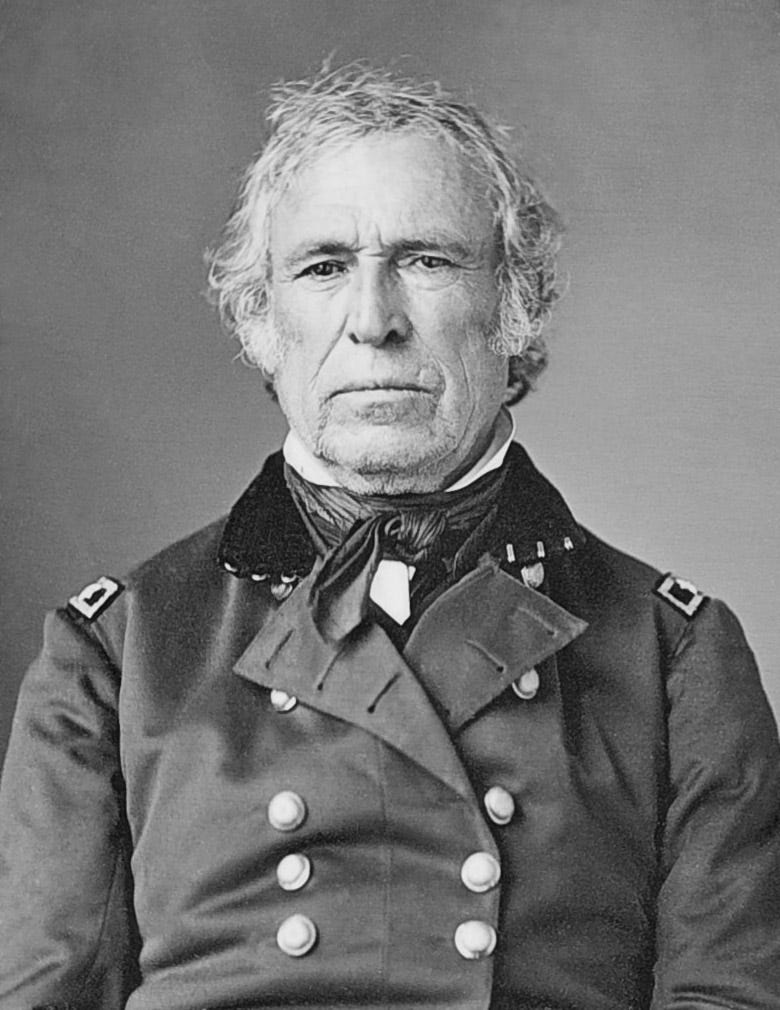

Zachary Taylor wasn't the first American general to be talked into becoming president. Nor was he the last. But he was the least distinguished. Fortunately he recognized his limitations amid the circumstances in which he found himself. Unfortunately he failed to halt the country's slide toward civil war.

Unlike George Washington and Andrew Jackson before him, but like Ulysses Grant and Dwight Eisenhower after him, Taylor was a career soldier. At the time of his 1848 election, he’d been four decades in uniform. He wasn't eager to exchange his general’s jacket for the suit coat of a politician, but he had come to despise James Polk, the Democratic president, who seemed to put partisanship above patriotism during the war with Mexico. And so when Whig leaders told Taylor only he could save the country from another corrupt administration, the general let his name be put forward for nomination. He won the nomination and the election that followed.

He understood what he was getting into. “I am conscious that the position which I have been called to fill, though sufficient to satisfy the loftiest ambition, is surrounded by fearful responsibilities,” Taylor said in his inaugural address. He had no intention of governing alone. “The legislative and judicial branches of the government present prominent examples of distinguished civil attainments and matured experience, and it shall be my endeavor to call to my assistance in the executive departments individuals whose talents, integrity, and purity of character will furnish ample guaranties for the faithful and honorable performance of the trusts to be committed to their charge."

The war that had made Taylor's presidency possible of attainment also made it impossible of successful execution. The foremost conundrum was what to do with the western territories acquired by the war. For thirty years the free North and the slave South had wrestled over new territories, with each side determined to add to its weight in Congress. In 1849 slave states and free states were evenly balanced: fifteen of each. The populous North already controlled the House of Representatives. If the South lost the Senate, its future would be grim. Southerners might decide to leave the Union.

Taylor was a Virginian by birth and an unapologetic slave holder. Yet he was a Unionist by conviction and by the oaths he had sworn as an officer and as president. He feared that an extended debate over slavery in the territories would inflame Congress and play into the hands of southern zealots seeking a pretext for secession.

He tried to preclude the debate. His plan was to encourage California to skip the territorial stage and immediately submit a state constitution to Congress. He sent an agent to California to make this happen.

Californians had the same idea and were already working on their constitution when Taylor 's agent arrived. They delivered it to Congress for the start of the 1850 session. As all had expected, the California constitution forbade slavery.

A president with a grander vision of his role might have attempted to take charge of the controversy that ensued. Taylor was content to leave the matter to Congress, where Henry Clay, whom Taylor had defeated for the Whig nomination, crafted a several-part compromise designed to appeal to moderates in both North and South. Taylor stood aside while the legislature became consumed by what would be the Compromise of 1850.

Southerners accused northerners of wanting to extinguish slavery. Northerners accused southerners of seeking to impose slavery upon the whole nation. Taylor's refusal to align with either side opened him to both sides’ fire.

In private he made clear there were limits to his forbearance. Thurlow Weed was a Whig from New York who visited Taylor during this period. “The president was walking rapidly to and fro," Weed recalled later. "‘Did you,’ said he, with an oath, ‘meet with those traitors?’ Then, in an excited manner, and in strong language, he proceeded to relate what had passed between them and himself. They came, he said, to talk with him about his policy upon pending slavery questions; and when they were informed that he would approve any constitutional bill that Congress might pass, and execute the laws of the country, they threatened a dissolution of the Union; in reply to which he informed them that, if it became necessary in executing the laws, he would take command of the army himself, and that, if they were taken in rebellion against the Union, he would hang them with less reluctance than he had hung deserters and spies in Mexico!"

Things didn't come to that while Taylor lived. Which wasn't much longer. On the 4th of July in 1850 Taylor was seen eating iced cherries. He subsequently complained of stomach distress. Whether the cherries had anything to do with it was never determined, but the ailment intensified and carried him off five days later, at the age of 65.

Taylor foresaw his end. "I should not be surprised if this were to terminate in my death,” he said. "I did not expect to encounter what has beset me since my elevation to the presidency. God knows I have endeavored to fulfill what I conceived to be an honest duty.”

Taylor's patience helped ensure passage of the Compromise of 1850, which bought the nation a decade to prepare for its sectional showdown. Whether this was a good thing or a bad thing is impossible to say. A civil war in the 1850s might have been less terrible than the one in the 1860s. But it might not have been. And it might not have been as decisive as the one in the 1860s.

Taylor's presidency provides another example of why historical judgments should always be rendered with humility. We know what did happen. We can't know what would have happened if what did happen didn't.

The South never really gave up, in spite of losing, on paper at least, the Civil War. They instituted Jim Crow, which prevented Black people from attaining true, equal citizenship with white parts of the country. To some extent, in various parts of the country, our Black citizens still struggle for equality. And at present, in the persons of Donald Trump and Pete Hegseth, we must fight AGAIN to bring back equal rights for all people of color. It is our Original Sin and we still have not put it to rest. I often wonder if we ever will.

What I like about this substack is how you remind your readers about “history’s orphans” (Taylor, Polk just to name a few) keep up the good work.