Wishful neutrality?

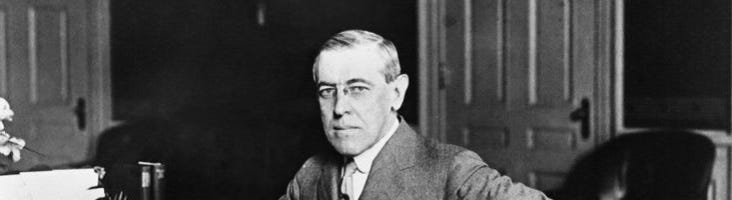

In August 1914, a few weeks after the outbreak of World War I in Europe, Woodrow Wilson delivered a message to Congress and the American people. “I suppose that every thoughtful man in America has asked himself, during these last troubled weeks, what influence the European war may exert upon the United States,” the president said, “I take the liberty of addressing a few words to you in order to point out that it is entirely within our own choice what its effects upon us will be and to urge very earnestly upon you the sort of speech and conduct which will best safeguard the nation against distress and disaster.”

Wilson observed that the United States had had no part in the coming of the war. And Americans need have no part in its fighting. Yet remaining aloof would require forbearance by the American people. “Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned.” This wouldn't be easy. Ties of heritage and history linked Americans to the opposite sides in the war. “It is natural and inevitable that there should be the utmost variety of sympathy and desire among them with regard to the issues and circumstances of the conflict. Some will wish one nation, others another, to succeed in the momentous struggle. It will be easy to excite passion and difficult to allay it."

Passion’s allaying was crucial. “Americans all, bound in honor and affection to think first of her and her interests, may be divided in camps of hostile opinion, hot against each other, involved in the war itself in impulse and opinion if not in action." Americans’ divisions of opinion might prevent America from acting as it should—“as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation.”

Wilson concluded with a plea to his compatriots. “I venture, therefore, my fellow countrymen, to speak a solemn word of warning to you against that deepest, most subtle, most essential breach of neutrality which may spring out of partisanship, out of passionately taking sides. The United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name during these days that are to try men's souls. We must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another."

Wilson's plea didn’t keep the United States out of World War I, although it helped delay America's entry. Yet his argument resonates still. Never in history, even during Wilson's time, have Americans been so deeply divided by a foreign war as they are today. College campuses, city streets, newspaper pages, television programs and social media platforms have resounded with heartfelt and often angry advocacy of Israel's cause on one side, and the Palestinians' cause on the other. Jewish Americans and Arab and Muslim Americans credibly fear violence against themselves and their communities; some on each side have already suffered violence. Political alliances of long standing are fracturing; the fallout among Democrats might cost Joe Biden reelection.

This last possibility underscores something Wilson didn’t stress in his speech but lived to experience. The divisions regarding the European war soured and hardened American attitudes in politics at home. The constructive cooperation between parties that had characterized the Progressive era from 1901 to 1914 diminished and died. Suspicion of immigrants became more open and virulent, leading to the first comprehensive immigration restrictions in 1924. Prohibition and woman suffrage were weaponized as tools for securing middle-class values against immigrants and other perceived challengers. And though America helped the Allied Powers win the war, Americans quickly grew disenchanted with foreign affairs, rejecting the Versailles treaty and turning their backs on the world for the next two decades.

The conflict between Israel and Hamas isn’t as big a deal as World War I. The blowback from the former will almost certainly be less than from the latter. Yet the American political mood might be more brittle now than in Wilson’s time. Today’s most ardent advocates of the opposing sides aren’t any more likely to heed calls for calm than their counterparts in Wilson’s day. But the rest of us, and America as a whole, would benefit from our weighing his words carefully. In times of furor, a few deep breaths are always beneficial.

Regarding World War 1 I think it's possible to pauseit that World War 2 would have never happened. Had world war one not occurred and ended the way it did.

What would have been the bad outcome had germany won and france in england lost? Would there have been a bad outcome?