Why?

Or what?

There was a time when historians hoped to emulate scientists. Clio's crowd observed the plaudits and pecuniary rewards bestowed upon the followers of Newton and wanted some for themselves. They never got their wish. The reasons for their failure were several, but none more important than their focus on the wrong question.

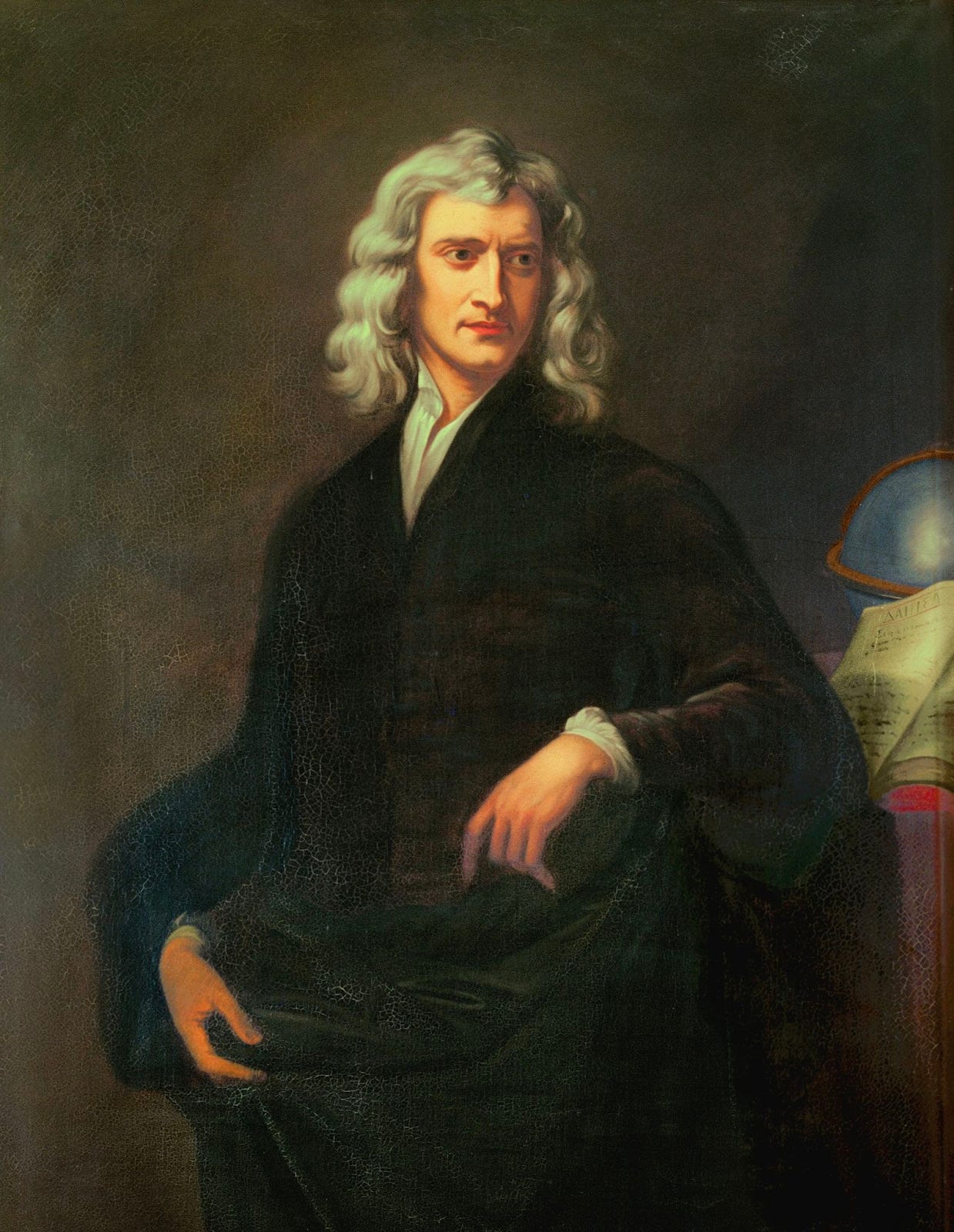

Scientists had once been philosophers, along with historians. They asked why things happen, just as the historians did. But about the time of Newton, they realized the futility of asking why. Instead they focused on what.

The great scientific triumph of this era was Newton's law of universal gravitation. Newton extrapolated from a falling apple to the motions of heavenly bodies. His law, wholly contained in a single formula, said nothing about why bodies fall toward other bodies. It simply described, with unprecedented precision, the fall itself.

This was enough to give his law tremendous power. It provided dates to eclipses and planetary conjunctions far back in the past; it predicted such events far into the future. It governed the motion of tides and the flight of cannonballs.

Newton had no causative explanation, no theory. Massive objects were attracted to each other because. . . because they were attracted to each other.

Newton's audience was willing to accept his causeless explanation because it worked. And because inanimate objects like cannonballs and comets were too stupid to seem to require elaborate explaining. Aristotle had said that heavy objects fall because it is in their nature to fall. Newton recognized that this was not an explanation but a tautology. So he dispensed with the charade.

Historians, in contrast to Newton, deal with objects—humans—that are all too animate. The actions of humans cry out for explanation. Asking why is much of what makes us human. Cows don't ask why rain causes the grass to grow. Not even great apes or whales seem concerned about causation. (Correlation is a different matter. When porpoises herd shoals of fish to eat, seabirds know to gather for the spoils.)

The problem with asking why is that there's no termination point, as many parents of inquisitive children know. Why did that man yell? Because he was angry. Why was he angry? Because that other driver cut him off. Why did the other driver cut him off? Maybe because she was in a hurry. Why was she in a hurry? And so on.

The why questions have the same problem handling bigger issues. Why is there a universe, to take the biggest one. Religion offers an answer, but the answer merely kicks the question down the road. There's a universe because God made the universe. Why did God make the universe? Because that's what God does.

Those who are unpersuaded by religion either plead ignorance as to why the universe exists or say it's because that's what a universe does. A non-existent universe is a logical impossibility. Anyway, the fact that we're here asking why the universe exists requires the existence of the universe. Cogito ergo cosmos, so to speak.

Scientists stopped being philosophers when they stopped asking why. They became more useful to our species—for a time, at any rate. The jury remains out on the scientific revolution; we'll have to see whether its products and by-products—including nuclear weapons, artificial intelligence and carbon dioxide—prove our undoing.

Historians are still philosophers because they still ask why. They'll never be scientists, and they shouldn't be. Yet they could make themselves more useful by devoting more energy to asking what. Set aside the arguments about causation for a moment and simply describe what happened. Do it with detail and flair. This has always been what draws lay people to history. The human drama doesn't require the embellishment of theory.

If readers and students form their own conclusions about why things happen—and they will, because evolution has wired the habit into us—that's their own affair. And they'll be better off for having done it themselves.

Brands writes: "The problem with asking why is that there's no termination point, as many parents of inquisitive children know." My wife and I don't have children, but what he says is certainly true. Why is this one of Brands' better essays? Because it's both interesting and true. Why is it interesting and true? Because I find it so. Why do you find it so? etc., etc.