When the world met Washington

Courier, diplomat, spy

“It was thought adviseable by his Honour the Governor to have the following Account of my Proceedings to and from the French on Ohio committed to Print,” wrote the young man who had returned to Williamsburg just in time for this twenty-second birthday. George Washington apologized for the unpolished language of his field journal. “There is nothing can recommend it to the Public, but this. Those Things which came under the Notice of my own Observation, I have been explicit and just in a Recital of:—Those which I have gathered from Report, I have been particularly cautious not to augment, but collected the Opinions of the several Intelligencers, and selected from the whole, the most probable and consistent Account.”

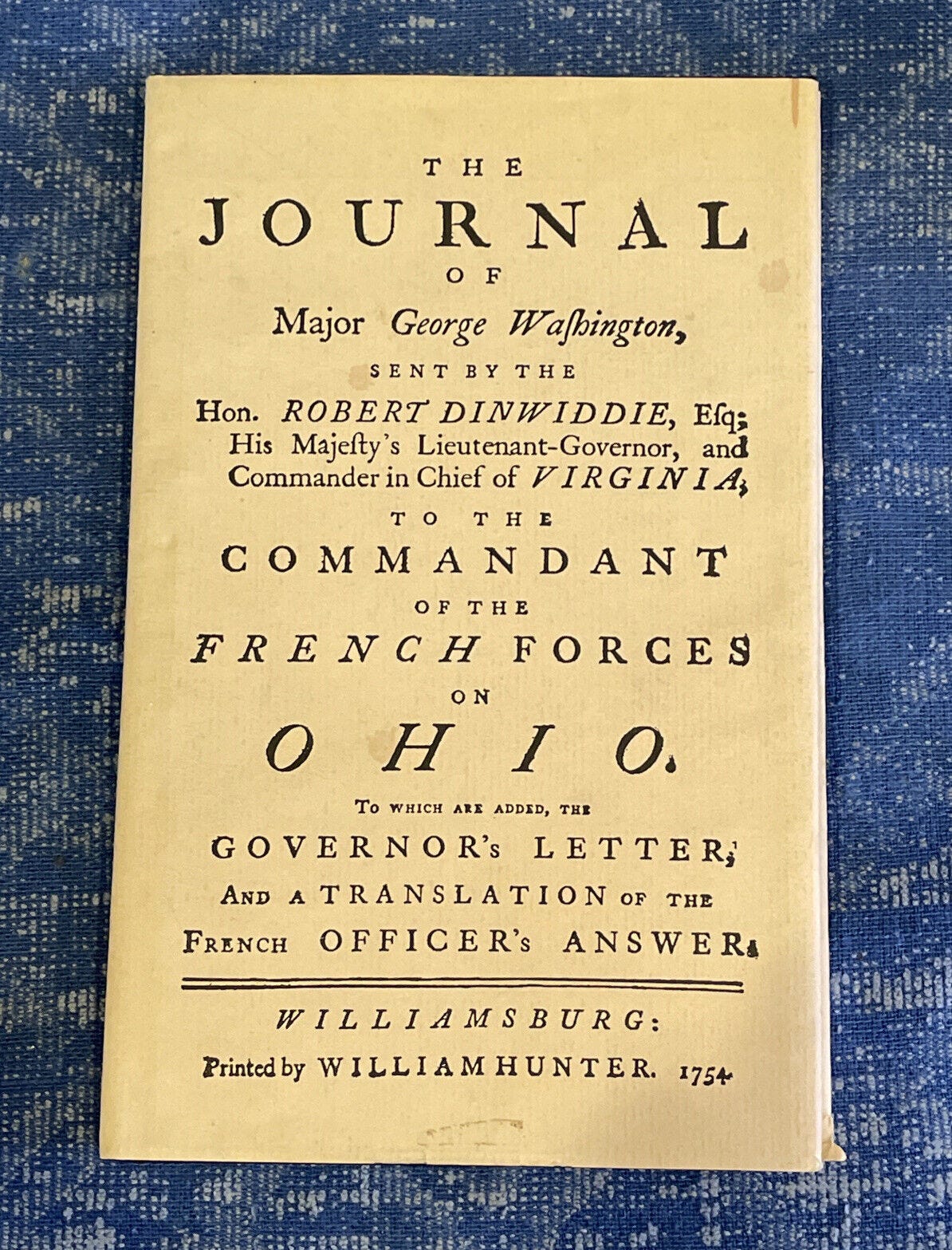

The governor was Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia, who had dispatched Washington to Ohio, the watershed of the river of that name, then in dispute between Britain and France. Dinwiddie, acting for the British crown, had directed Washington to deliver a letter to the senior French officer in Ohio telling him and his soldiers to clear out. Washington’s journal, published by printer William Hunter of Williamsburg in early 1754 and reprinted in newspapers in several other of the British colonies in America, would tell of the response to this ultimatum.

The matter was of intense interest in British America. Britain and France had fought for control of North America thrice already. A fourth war appeared likely. Such a conflict would touch the lives of colonists from New England to Georgia. Those living near the frontier shuddered at what a war would unleash: raids by Indians allied with the French upon isolated homes and hamlets. In time of general peace, the frontiersmen could just about protect their families against the Indians whose lands they encroached upon. In time of war, when the Indians were armed and encouraged by Britain’s mortal enemy, all bets were off.

Yet concern over war extended far beyond the frontier. Merchants of New England and tobacco planters of the South depended on the trade routes to Britain. War would bring out the French navy to interdict the trade and seize vessels and cargo. French warships and the marines they carried could threaten coastal communities directly.

There was another class of Americans with a special interest in Ohio. These were the speculators who had purchased land rights in the region or hoped to. In the century and a half of British settlement in America, no business enterprise had enriched so many as the simple proposition of acquiring land rights west of the current frontier, waiting for the next wave of settlers to come, and selling the rights at appreciated value. One company of speculators called itself the Ohio Company. Others had similar names and the same business plan.

The lives of the speculators, many of whom lived in Britain, weren’t so clearly at risk as those of the frontier families in case of war against France over Ohio. But their fortunes were. The value of their land titles would rise, even soar, if George Washington’s printed journal contained the good news of French agreement to withdraw from Ohio peacefully. The value would decline, perhaps plummet ruinously, if the journal brought word of war. No wonder the first literary attempt by the young major of Virginia militia inspired such interest.

“On Wednesday the 31st. of October 1753 I was Commission’d & appointed by the Honble. Robert Dinwiddie Esqr. Governor &ca. of Virginia to visit & deliver a Letter to the Commandant of the French Forces on the Ohio,” Washington’s journal began. The author didn’t mention why he was the one to receive the commission. At twenty-one, he might have seemed a bit green for such a weighty assignment. The answer came in two parts. One was that he knew the western country from having been a land surveyor in the region during the previous few years. The other part of the explanation also accounted for his appointment as an official surveyor at the tender age of seventeen. Washington had patrons who vouched for his ability and integrity. Two were his elder half-brothers Lawrence and Augustine Washington. Lawrence had become a second father to George Washington following their father’s early death. A third patron was Lawrence’s father-in-law, Lord Fairfax. Lawrence and Augustine were charter members of the Ohio Company, whose roster include Robert Dinwiddie. The elder brothers made Washington an associate of the company. Fairfax held many thousands of acres of western land by royal grant. It was on Fairfax property that Washington cut his surveying teeth.

Simply getting to and from Ohio in winter was a challenge. Washington’s journal related long rides in the rain and bivouacs in the snow. “From the first Day of December ’till the 15th. there was but one Day but what it rain’d or snow’d incessantly,” he wrote. “And throughout the whole Journey we met with nothing but one continued Series of cold wet Weather, which occasioned very uncomfortable Lodgings, especially after we had left our Tent, which was some Screen from the Inclemency of it.” Swollen creeks and rivers had to be crossed. Feed for horses had to be acquired and carried. Washington’s previous experience served him well. The worse the conditions the better he thrived.

Trickier were relations with the Indians encountered by Washington and the party he enlisted. The Indians of Ohio tried to play the French against the British, choosing one side and then another. By this means they hoped maintain as much independence and autonomy as possible. It was a delicate business, as the French and the British tried to force the Indians to choose sides. Should war break out, the pressure to choose would increase. In the meantime, it was often hard for one like Washington to tell which tribe or part of tribe was on which side. Washington’s small company wasn’t large enough to defend itself against concerted attack. It had to survive by Washington’s wits and the persuasive abilities of the translators who accompanied him.

Washington wasn’t simply a courier. He was also a spy. He gathered information on French intentions and preparations. His party encountered four Frenchmen who had deserted from a French military force. “I got the following Account from them. They were sent from New Orleans with 100 Men, & 8 Canoe load of Provisions, to this Place.” At the time of the writing Washington was at Logstown, an Indian village near the Forks of the Ohio, the future site of Pittsburgh. “They expected to have met the same Number of Men, from the Forts this Side Lake Erie, to convoy them & the Horses up, but were not arriv’d when they ran off.” The French controlled Lake Erie from their bases in Canada. What the deserters were saying was that the French were trying to form a link in Ohio between New Orleans and Canada. This would bode ill for the British.

Washington quizzed them about the location and size of forts on the Mississippi and Ohio. They obliged, for a compensation. “They inform’d me that there were four small Forts between New Orleans & the Black Islands”—Isles Noires, or Illinois—“Garrison’d with about 30 or 40 Men, & a few small Pieces of Cannon in each. That at New Orleans, which is near the Mouth of the Mississippi, there is 35 Companies of 40 Men each, with a pretty strong Fort, mounting 8 large Carriage Guns; & at the Black Islands there is several Companies, & a Fort with 6 Guns. The Black Islands is about 130 Leagues above the Mouth of the Ohio, which is 150 above New Orleans.” The readers of Washington’s journal couldn’t help being alarmed.

The reaction of the French to Washington’s approach didn’t improve the British state of mind. The commandant accepted Dinwiddie’s letter, but as it was written in English, a language he didn’t read, he had to get it translated. Washington lounged around the fort, taking mental notes, which he later transcribed. “It is situated on the South or West Fork of French Creek, near the Water, & is almost surrounded by the Creek, & a small Branch of it which forms a Kind of an Island, as may be seen by a Plan I have here annexed.” The plan was for Dinwiddie’s eyes only. It was not included in the printed journal. “Four Houses compose the Sides; the Bastions are made of Piles drove into the Ground, & about 12 Feet above sharpe at Top, with Port Holes cut for Cannon & Small Arms to fire through; there are Eight 6 lb. Pieces Mounted, two in each Bastion, & one of 4 lb. before the Gate: In the Bastions are a Guard House, Chapel, Doctor’s Lodgings, & the Commander’s private Store, round which is laid Platforms for the Cannon & Men to stand on: there is several Barracks without the Fort for the Soldiers dwelling, cover’d some with Bark, & some with Boards, & made chiefly of Logs.”

Washington received his reply, in the form of a letter from the French commandant to Dinwiddie. The officer said the governor’s letter had been forwarded to his own commander in Canada. But as to Dinwiddie’s demand that the French retire from Ohio, the commandant could answer at once. He would not comply. “I am here by virtue of the orders of my General, and I entreat you, Sir, not to doubt for a moment that I have a firm resolution to follow them with all the exactness and determination which can be expected of the best officer.” He denied that France had disturbed the peace between it and Britain. “I do not know that anything has happened in the course of this campaign which can be construed as an act of hostility, or as contrary to the treaties between the two Crowns, the continuation of which interests and pleases us as much as it does the English.” In other words, Governor—shove it.

Washington hadn’t read the French commandant’s letter to Dinwiddie, rather delivering it under seal. Anyway, he didn’t read French. But it was translated and printed with Washington’s journal. Readers reckoned that France wasn’t going to abandon Ohio without a fight.

The readers must have suspected that when the fight commenced, the resourceful Major Washington would be in the thick of it.

Glad you shared this brief look at a formative time in the young life of a nation's founding fathers. Washington had many talents. He was a skilled surveyor so he knew his way around the dense forests of the Ohio Valley. He also seemed to understand the ways of the British, that is obvious, but also the French and the Indian tribes in this part of the territory and decisions had to be made if there was going to be any peace in the region. You needed courage having been thrown into this turmoil with violent conflicts ready to break out at any time. There also was a steadiness about Washington's observations and no doubt he was looking to the future thinking where would Americans land once some accomodation was reached with the many parties involved. All this would serve Washington well as would command in time the American revolutionary forces.

Really so much to think about in these early times in Washington's life.