When Ford pardoned Nixon . . .

Whose interest was served?

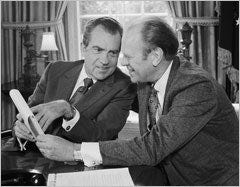

Fifty years ago this last August, Gerald Ford offered Richard Nixon a pardon for any crimes he might have committed in the context of the Watergate scandal. Nixon accepted the pardon.

Prosecution of the former president stopped in its tracks. Many of those Nixon had considered his political enemies—a large group—were outraged. Even some who had taken no particular position on Watergate and Nixon's culpability registered unease at the shortcircuiting of the judicial process. No one is above the law, they said. Justice ought to have run its course.

Ford justified the pardon on grounds of national interest. Calling the Watergate affair “an American tragedy in which we all have played a part," Ford declared, ”It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."

The possibility of a pardon had emerged even before Ford became president. As the evidence against Nixon mounted, his chief of staff, Alexander Haig, visited the vice president to sound out his assessment of the situation. Haig related that members of the White House staff had been talking about the possibility of Nixon's resignation and a pardon, either by Nixon himself before he left office or by Ford after Ford acceded to the presidency. “He asked if I had any suggestions as to courses of actions for the President," Ford wrote later. “I didn't think it would be proper for me to make any recommendations at all, and I told him so."

Haig certainly couldn't have expected anything more. But he might well have expected less, to wit a warning from Ford that Nixon must not anticipate a pardon from him. That Ford had not given such a warning must have been encouraging to Haig, and through Haig to Nixon. Nixon resigned shortly thereafter.

Ford waited a few weeks before taking up the Nixon case. With the nation still reeling from the oil shock that accompanied the 1973 Middle Eastern war and the inflation it aggravated, and with the outcome of the Vietnam war in the balance, Ford had his hands full otherwise. He also had a credibility problem. As a doubly unelected president—having been elected to neither the presidency nor the vice presidency, indeed to nothing broader than his congressional district in Michigan—he hesitated to break new constitutional ground by intervening in the possible prosecution of a former president. Nixon's resignation precluded impeachment, thereby reducing its political salience. Ford hoped the American people would lose interest and prosecutors would do the same.

This didn't happen. Ford stepped in and delivered the pardon.

His popular approval rating suffered an immediate blow. Overnight it fell by 20 points. More than a few of Nixon's critics now became critics of Ford, alleging that a bargain had been struck between the two, with Nixon getting a pardon and Ford getting the presidency. Ford felt obliged to deny any such thing in testimony before the House judiciary committee.

Distrust on the subject dogged Ford for the rest of his presidency. He took some comfort from the line of reasoning that Nixon's acceptance of the pardon connoted a confession of guilt. For years he carried in his wallet a clip of an excerpt from a 1915 Supreme Court decision distinguishing an amnesty from a pardon. “The latter carries an imputation of guilt; acceptance a confession of it," Ford's clip said. By accepting Ford's pardon, Nixon had essentially pleaded guilty. This admission was more important to the national interest than any fine or prison time the former president might have paid or served, Ford told himself and others.

Not everyone saw things that way, including Nixon. The statement that Ford clung to was merely an obiter dictum by one of the justices in the 1915 case, an observation that had no value as precedent. An opposing line of reasoning to Ford's held that a person might accept a pardon not out of a feeling of guilt but out of fear that the courts would deliver an erroneous verdict.

This was the position Nixon took. “I was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate,’’ Nixon said in his letter accepting the pardon. “No words can describe the depth of my regret and pain at the anguish my mistakes over Watergate have caused the nation and the presidency.” But he said not a word suggesting guilt of any crime.

He never did. Many Americans thought Nixon had gotten away with a final fast one. Some appreciable number blamed Ford, either for conniving with Nixon or having been played by Nixon. When Ford lost a close race to Jimmy Carter in 1976, it was entirely plausible to conclude that the Nixon pardon had made the difference.

Perhaps ironically, perhaps predictably, Ford's very failure softened the accusations against him. If indeed he had conspired to gain the presidency, he had failed to keep it. If he hadn't conspired, then his voluntary pardon of Nixon was an honest, well-meaning act that cost him the presidency.

This latter was the view that took hold, to the point that in 2001 the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation bestowed its Profiles in Courage award on Ford.

By the time Ford died in 2006, conventional wisdom seemed to accept his judgment that the Nixon pardon was necessary get the nation past Watergate to issues of greater importance.

Yet when Donald Trump ran afoul of federal prosecutors in the early 2020s, the Nixon pardon came in for new scrutiny. Trump's critics wished Ford had let the prosecution of Nixon proceed. The question of presidential immunity would certainly have come up and might well have been settled by a less politicized Supreme Court. To be sure, the Roberts court might have overturned a 1970s precedent on immunity—as it overturned an abortion precedent from the same era—but it would have had to work harder than it did in the absence of a Watergate precedent.