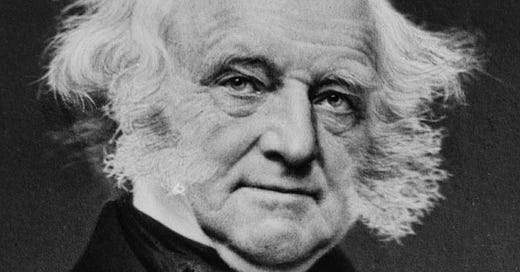

Andrew Jackson was a difficult act for Martin Van Buren to follow, for two reasons, one general and one specific. The general reason was that the general, as Jackson was called before and after his presidency, was the great hero of the age. Van Buren was not. The specific reason had to do with the Specie Circular issued by the treasury department in the last months of Jackson's presidency. It specified that only specie—gold and silver coin—would be accepted in the sale of federal lands. The hard money was less plentiful than the paper notes which had been accepted previously, and the decision drove down the price of land, ruining many speculators and triggering the Panic of 1837, which cast a pall over the country for the next several years. Van Buren was the first president to experience what would become a truism in American politics: that bad times in the economy are bad times to be president.

Van Buren did what he could to deal with the economic troubles, which stemmed from one of the more dubious accomplishments of Jackson's presidency. A bank hater, Jackson had closed the Bank of the United States and transferred the government's deposits to state banks, which he considered less threatening. These were the institutions that went on the paper-money-issuing spree that created the land bubble the Specie Circular burst. Van Buren reorganized the government's financial accounts by persuading Congress to create an “independent treasury,” which effectively made the federal government its own banker, independent of private banks.

The measure failed to revive the economy, leaving Van Buren to ponder what he could accomplish in the one term to which he was likely to be limited by voters. If he couldn't continue as president, he hoped the principles for which he stood could go on. These were the principles of Jackson, his mentor, and they were the principles of the emerging democracy.

Better than any president before or after him, Van Buren understood that political principles succeed only when they are embodied in political organizations. He had entered politics in New York as part of the “Albany Regency,” an early version of the political machines that would dominate state and local politics until the mid-20th century. Aspiring beyond his home state, Van Buren hitched his star to that of Jackson, and he demonstrated such an ability to forge alliances and deliver votes that he was called “the Magician” by friend and foe alike. Jackson made him secretary of state and then, in Jackson's second term, vice president.

Meanwhile Van Buren fashioned the modern Democratic party as the institutional version of Jackson. The party traced its roots to Thomas Jefferson's Republicans, but that party had lost its focus upon the demise of the Federalists after the War of 1812. Some of the old Republicans followed Henry Clay into the Whig party, which embraced the pro-business, pro-federal ideas of the old Federalists. The Jacksonian Democrats, guided by Van Buren, favored farmers over merchants, and the states over the feds.

At Van Buren's urging, the Democrats held their first national nominating convention in 1832, establishing a quadrennial tradition that hasn't been broken yet. Nominees for president had previously been chosen ad hoc by congressional caucuses or state legislatures. The convention format gave structure to the nominating process even as the gathering itself allowed Democrats from all around the country to meet and confirm their shared beliefs.

The 1832 convention adopted a rule that contributed significantly to the longevity of the Democratic party. The winning candidate for the presidential nomination required the votes of two-thirds of the delegates. Over time this made for some marathon conventions, but it meant that the party nominated men the great majority of Democrats could get behind. It allowed the Democrats to survive the sectional crisis that destroyed the Whigs, and it enabled them to continue as a national party during the century the second Republican party—of Abraham Lincoln—was essentially shut out of the South.

A party is a force for good or a force for bad, depending on its policies of the moment. The policies of the Democrats were by no means all good ones. But under the Constitution, parties are essential to the operation of the government, and no party has been more essential for longer than the Democratic party—or the Democracy, as 19th-century Democrats styled themselves collectively.

For many decades Democrats gathered every spring in cities and towns around the country for Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners, in honor of the patron saints of their party. Historically minded guests also toasted Martin Van Buren, without whom the dinners and the party itself might not have endured so long.

A bit of trivia: Van Buren was also the only president who spoke English as his second language. He was born into a Dutch-speaking family and learned English only after going to school. Of course, that may be linguistic folklore. Anyone out there know for sure?

The jefferson jackson dinners are now largely called legacy dinners