The framers of the Constitution were practical men. Some knew political theory, but all appreciated political practice. They were not Platonists but Aristotelians, less concerned with what something was than what it did. They understood power, and recognized that power is action rather than essence.

And so, late in their proceedings at Philadelphia, when they turned their attention to what should happen in the event of a president's death, they confined themselves to the disposition of the president’s powers. “In case of the removal of the President from office, or of his death, resignation, or inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President,” they wrote in Article 2. They added, “And the Congress may by law provide for the case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what officer shall then act as President, and such officer shall act accordingly, until the disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.”

By emphasizing “powers and duties,” and saying that these should "devolve on the Vice President," the framers certainly gave the impression that the vice president would remain vice president, with new powers—those of the president—added. And when the framers talked about what should happen in case of the death of both the president and the vice president, they continued in the same vein, twice stating that the replacement would “act" as president. For how long? “Until a President"—a real president—”shall be elected."

Beyond their practical political views, the framers had reason for writing as they did. They set no limits on how long a president could serve. They assumed the office would go to experienced, mature individuals. Their model was George Washington, who was indeed experienced and mature. Alexander Hamilton expressed the wish that presidents might serve for life. The convention as a whole didn’t support this proposition explicitly, but the delegates allowed for the possibility that a president might be elected again and again, even until he died, thus becoming in practice a president for life. In other words, they expected that the death of a president in office might be a common occurrence. And they did not want the vice president to become president, in the way that the heir to the throne of Britain became monarch on the death of his or her predecessor. No, the vice president would merely “act" as president. For how long? Until the election of the next president. Presidents must be elected; there would be no accidental presidents in the American republic.

The framers wrote these words in the summer of 1787. Events didn’t transpire in the way many of them expected. George Washington retired after two terms. His example caused his successors to limit themselves to two terms. Eight presidents entered office, and all left alive and kicking. The question of presidential succession was almost forgotten.

Until William Henry Harrison died a month after his inauguration in 1841. By this time another development the framers hadn’t foreseen had occurred. Presidents and vice presidents were now typically elected as teams. Originally the president and the vice president were antagonists, with the latter being the runner-up in the electoral voting for president. There was greater reason now than before to expect continuity of policy should a president die and his vice president take up the reins.

But another unanticipated twist undercut this effect. The parties—themselves a surprise to the framers—made a practice of balancing the tickets of candidates for president and vice president, typically pairing a presidential candidate from one part of the country with a vice presidential candidate from another part. If a president died, though policies might remain much as before, or at least within the bounds of party acceptability, the new man signing or vetoing bills and nominating judges and appointing executive department officials could have a very different sectional perspective.

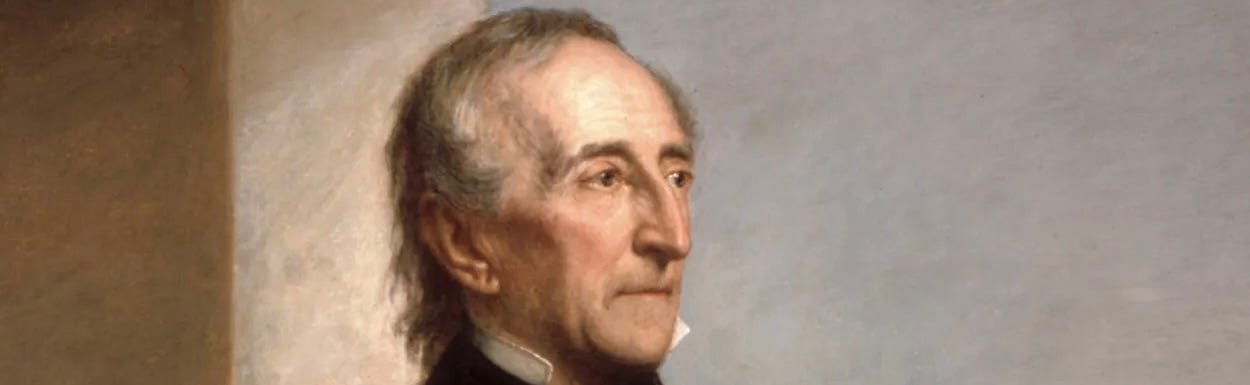

The result of all this was that when Harrison, a Virginian by birth but long associated with the Northwest as governor of Indiana Territory, died of pneumonia, and the responsibilities of the presidency fell to John Tyler, a proud and permanent Virginian, Americans at large had little idea what the transfer portended. Moreover, although both men were Whigs, Tyler’s southern Whiggism respected the prerogatives of the states far more than did the fed-friendly northern Whiggism of Harrison.

Lastly, Tyler lacked the support of Henry Clay, the leader of the Whigs in Congress. Clay hadn’t considered Harrison a true rival, on account of Harrison’s age—sixty-eight at inauguration—if for no other reason. Tyler, a generation younger than Harrison, might become a very threatening rival. Clay had run for president twice before, unsuccessfully. He wasn’t getting younger. If he was ever to be president, 1844 might be his last chance. He didn’t intend to be blocked by Tyler.

Clay construed the language of Article 2 as saying Tyler would be acting president for the rest of Harrison’s term, not actual president. Clay’s Whig supporters—that is, most of the party—took the same position.

But Tyler had other ideas. He found a sympathetic judge who administered the oath of office—the office of president. “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States,” Tyler said. The oath didn’t state explicitly that Tyler now was the president, but by uttering the same words as Washington, Adams, Jefferson and the others, Tyler made himself appear presidential.

He delivered an inaugural address. He insisted that members of his staff refer to him as “President Tyler” or “Mr. President.” He signed official messages and correspondence as “President of the United States.” Foreign governments addressed him as president.

Clay conspicuously did not. Yet at first Clay confined his opposition to this. But when Tyler vetoed a bill Clay guided through Congress that would create a new national bank, Clay led a revolt against Tyler. The cabinet secretaries Tyler had inherited from Harrison resigned en masse, and Whigs in Congress read Tyler out of the party.

The excommunication made Tyler more stubborn. He insisted more strenuously than ever that he was the real president. An impasse ensued.

Yet gradually something dawned on both sides in the fight. The framers had been right all along: the presidency is defined by its powers, not by the title of the office holder. And it is limited by its powers. Tyler had the power of the veto, and nothing Clay did could take that away. At the same time, the honorific “Mr. President” didn’t enable Tyler to break the blockade Clay set up around him.

Tyler served out the term he inherited from Harrison and left without a fight. Clay won the Whig nomination in 1844 but lost the general election to Democrat James Polk.

The next time a president died in office—Zachary Taylor in 1850—the question of whether Millard Fillmore became actual president or acting president didn’t seem worth contesting. The two conceptions turned out, in practice, to be the same. Fillmore was addressed as “Mr. President,” and so were all his successors who entered the White House similarly.

The Twenty-fifth Amendment, ratified in 1967, erased any residual doubt, in favor of Tyler. “In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.”

Tyler had the foresight to clarify the role of Vice President on becoming president and it has carried throught to our time. I am surprised he didn't use his new position to put himself into a prime spot from which to gain the next nomination. Or was the power of Henry Clay so great in the party the Tyler really had no chance particularly since Clay had failed a number of times earlier? I never followed the election against Polk but I guess that may have been an intriquing story as well. on the whole Polk was quite successful.