Theodore Roosevelt had been fascinated by ships and the sea since boyhood. As an undergraduate at Harvard he commenced his first book, The Naval War of 1812, which long remained the best work on the subject. In adulthood he devoured the writings of Alfred Thayer Mahan, whose The Influence of Sea Power upon History argued that the nations that controlled the waves controlled the world.

Hence it was only natural that Roosevelt, on being vaulted into the presidency by the assassination of William McKinley, took a deep interest in ongoing efforts by the United States to acquire rights to build a canal across Central America linking the Atlantic to the Pacific. An isthmian shortcut—saving several thousand miles of voyaging around South America—had been a hope of Americans since the California gold rush of the 1840s and 1850s. It appeared a possibility upon completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. It became a priority after the American annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and the Philippines in 1899.

The growing importance of a canal to the United States increased the price potential host governments thought they could charge for canal rights. Colombia controlled the shortest route, across the Colombian province that would become Panama. Roosevelt reasoned that a canal would benefit the host country by encouraging commerce and economic development; he deemed extortionate the payment Colombia was demanding up front. He supposed most of the money would line the pockets of Colombian insiders, and he was loath to underwrite the corruption.

Roosevelt wasn't the only one unhappy with the government of Colombia. Would-be rebels in Panama wanted a country and government of their own. To date their efforts had come to naught, but with a powerful friend like the president of the United States, they might finally succeed.

Roosevelt weighed his options. He could respect the sovereignty of Colombia and pay what that country was demanding. Conceivably he could pursue earlier ideas of digging a canal across Nicaragua or southern Mexico.

Or he could back the Panama rebels, in exchange for a deal on canal rights. Roosevelt was no stranger to toppling governments. He had been an outspoken advocate of war against the Spanish colonial government of Cuba, and when the Spanish-American War came, he fought gallantly on behalf of Cuban nationalism.

But the Panamanians weren't proposing national liberation so much as secession. And regarding the secession struggle he knew best—the American Civil War—Roosevelt consistently denounced secession as treason.

He pondered what an isthmian canal would mean. It would serve America commercially, at once becoming a highway of trade between the eastern and western parts of the country. It would enhance America’s naval power by linking the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. In this regard it would especially strengthen the Monroe Doctrine—the hands-off warning to intruders into the Americas—against challenges from naval upstarts like Germany.

Roosevelt was too young to have known the Manifest Destinarianism of America's mid-nineteenth century. But he fully shared its view that what was good for America was good for the world. An isthmian canal, he believed, would mark a major advance for human civilization. Getting the construction of a canal underway would make him a benefactor of humanity.

He refused to let the opportunity pass. An activist by temperament, full of nervous energy, Roosevelt always had to be doing something. What he did in this case was send word to the Panamanians that if they launched their revolt he would ensure its success. They did, and he did, and shortly afterward they agreed to the canal deal he sought.

Colombian officials were understandably outraged. They accused Roosevelt and the United States of piracy. Many in America complained that Roosevelt’s high-handedness would alienate all of Latin America except the new rulers of Panama.

The criticism stung Roosevelt. To members of his cabinet, some of whom shared the broader skepticism, he argued that his course was the only right one. They suggested he be satisfied with the outcome; defending himself simply made matters worse.

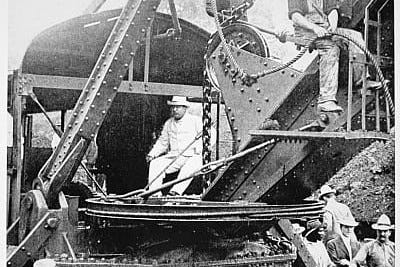

Construction on the canal commenced during Roosevelt's second term. He broke precedent by leaving American soil—previous presidents had stayed home while in office—to observe the work personally. He even tried his hand at the operation of a steam shovel.

He was never more thrilled than when the Panama Canal opened to traffic in August 1914. He thought his action in the matter was the greatest thing he had done as president.

Professor Brands,

I just posted this essay to my APUSH class web page. I also made the joke that you must be auditing the class-we just talked about this last Thursday! De Lesseps also has to get some credit for "selling" Panama as a better alternative for a canal than Nicaragua, while Gorgas' research and success on mitigating yellow fever and malaria kept people from dying in mass numbers during construction. (Thanks David McCullough for your book!) Have a great day-thanks for these essays.

As a Panamanian, I think a bit more nuance is due. Here is an article from FEE. https://fee.org/articles/how-wall-street-created-a-nation-j-p-morgan-teddy-roosevelt-and-the-panama-canal/