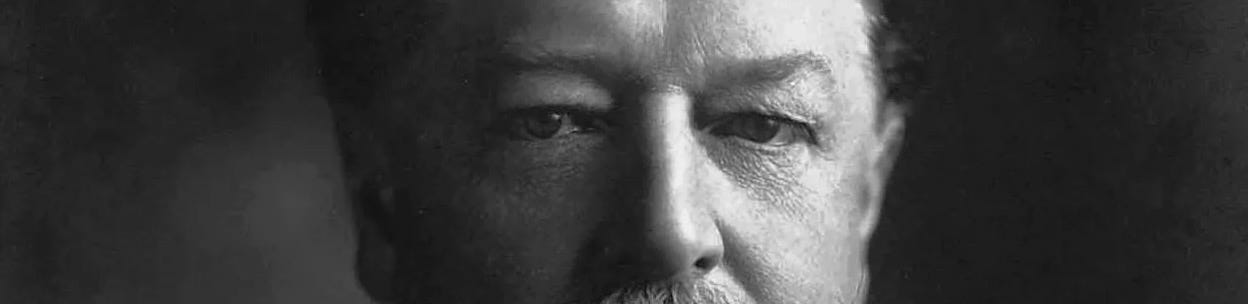

Life had been kind to William Howard Taft. He was book smart but also canny. “I always had my plate the right side up when offices were falling," he later observed. An Ohio judgeship fell onto his plate, and then a series of federal offices, starting with governor general of the Philippines and continuing to secretary of war. In that post he impressed Theodore Roosevelt, who concluded that Taft was just the man to follow him as president. Roosevelt's endorsement persuaded Republican progressives to back Taft. Republican conservatives were willing to accept Taft as the price of getting Roosevelt out of the White House. Taft sailed through the 1908 Republican convention and rode Roosevelt's residual popularity to victory in the general election.

Once elected, Taft experienced the epiphany that comes to every president upon inauguration. He was now the president. How he had won the office no longer mattered. He was grateful for Roosevelt's support, but he did not feel beholden to Roosevelt. He would govern as he saw fit.

What he saw and how he governed turned out to be more conservative than Roosevelt had expected. Roosevelt wanted to press the progressive case forward; Taft was content to consolidate what progressivism had already achieved. Taft continued and indeed accelerated the antitrust campaign Roosevelt had begun, notching a signal victory with a Supreme Court order for the breakup of Standard Oil. Yet in other areas, notably conservation, Taft made concessions to conservatives that Roosevelt deemed betrayal.

Roosevelt thereupon challenged Taft for the 1912 nomination. Roosevelt previously had said he would count his three and a half inherited years from McKinley as a full first term and would not run for a third. He had honored that pledge in 1908 but now appeared to be going back on it. Reporters asked him to explain. He said that he had meant no third consecutive term.

Primary elections were just coming into vogue. Progressives supported primaries as a way of breaking the hold of political bosses on the nomination process. In 1912, twelve states held Republican primaries. Roosevelt won nine, including in Taft's home state, Ohio. Roosevelt never needed convincing of his righteousness, but his string of victories persuaded him that he was still the favorite of the Republican party.

Taft had a choice. He could accept the will of primary voters and step aside in Roosevelt's favor. Or he could fight to keep the presidency.

The former course would please Roosevelt, naturally. This was no small consideration with Taft, who had considered Roosevelt his friend and was deeply pained by the rift between them. Yielding the nomination to Roosevelt would also allow the Republicans to retain the White House. In Roosevelt's last election, in 1904, the Rough Rider had won the largest popular majority in American history until then. There was every reason to think he would win a large victory again in 1912. A final reason for yielding to Roosevelt was that Taft had never enjoyed the presidency. His was a judicial temperament rather than an executive one. As a young lawyer his dream had been to be chief justice, not president.

Yet Taft had a stubborn streak. He didn't want to go down in history as someone who had kept the White House warm awaiting for Roosevelt's return. He was proud of what he had accomplished during four years, and he was willing to defend his accomplishments before the general public.

So he ordered his supporters to fight. Most states used other methods than primaries to select delegates to the national convention, and these methods remained under the firm control of the party bosses. Taft employed the powers of the presidency to persuade the bosses to choose delegates committed to him. In truth, not much persuasion was required, as most of the bosses were less enamored of Roosevelt than the primary voters were.

The Taft forces carried the convention and renominated the incumbent. Roosevelt thereupon bolted the convention and placed himself at the head of a third party, the Progressives.

Taft wasn't the last president to face a serious third party challenge. Harry Truman in 1948 and George H. W. Bush in 1992 had similar experiences. Yet Taft was the only incumbent to lose to the third party candidate. In the three-way race, Democrat Woodrow Wilson came first, Progressive Roosevelt came second, and Republican Taft came third.

If Taft had been the sort to be easily humiliated, the 1912 outcome would have given him cause. But he was philosophical, returning to Ohio to wait for another office to fall onto his plate. After the Republicans regained the White House following the 1920 election, Taft's plate caught the office he had always wanted. Warren Harding nominated him to be chief justice and the Senate confirmed the nomination. The last decade of Taft's life, at the head of the Supreme Court, was his happiest.

My epiphany tonight was reading your well chosen words: “Taft experienced the epiphany that comes to every president upon inauguration. He was now the president. How he had won the office no longer mattered.” That speaks to the ages.