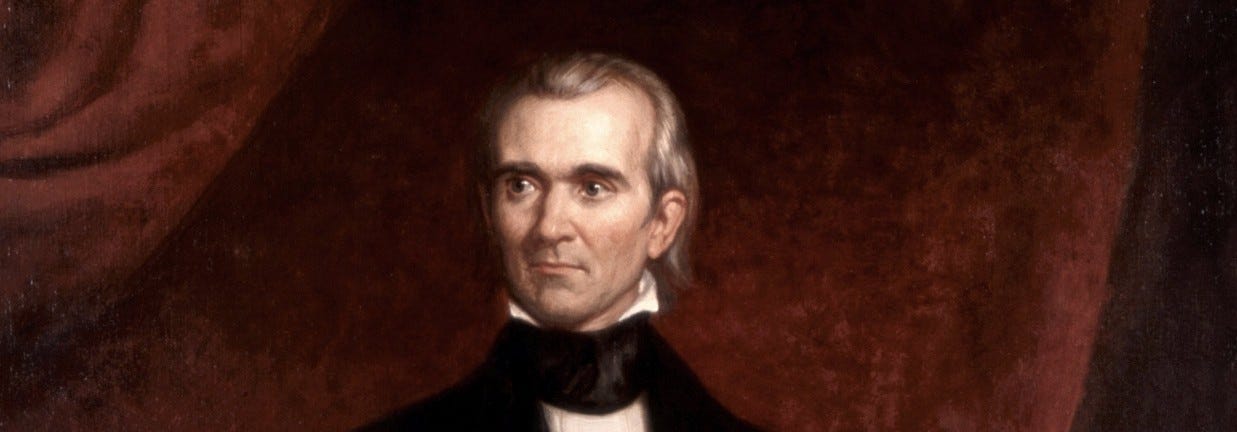

In an expansionist era of American history, James Polk was the most expansionist of all. Polk won the presidency in 1844 on a platform of expansion, promising the annexation of Texas, at that time an independent republic, and the acquisition of all the Oregon country, in dispute with Britain. His decisive victory at the polls knocked away the barriers that had caused Congress to withhold an offer of annexation to Texas. The deal was essentially done by the time Polk took office.

Yet a problem remained. Mexico had never surrendered its claim to Texas. Indeed Mexican armies had invaded Texas twice in recent years. Annexation by the United States threatened to bring the United States into conflict with Mexico.

Polk wasn't worried. If anything, he was encouraged. Polk's appetite for territory was the kind that grew with the eating. Annexation of Texas pushed America's southwestern border west by 800 miles. A mere 600 miles separated that new border from the Pacific Ocean in Mexican California. Polk examined his maps and decided the United States needed the bays of San Francisco and San Diego.

He initially hoped to purchase California from Mexico. But the Mexican government, having lost or about to lose Texas, was in no mood to relinquish California as well. Polk was left to consider other forms of persuasion.

Until this time, the government of the United States had never engaged in naked territorial aggression against another sovereign nation. To be sure, Americans had fought Indian tribes regularly. The United States had held the threat of military conquest of Spanish Florida over the head of Spanish diplomats in negotiations that resulted in the cession of Florida to the United States. The United States had invaded Canada during the War of 1812 and would have carved out parts of that British colony if the American troops had not been rebuffed. But Mexico was a fellow republic, which seemed to put it in a different category.

Not to Polk. If Mexico wouldn’t be moved by American dollars, it might be moved by American soldiers. Yet even Polk felt the need to cover aggression with a more respectable cloak. Besides not recognizing the independence of the Texas republic, Mexico disputed Texas’s interpretation of the border between Mexico and Texas. The Texans claimed the Rio Grande as the border; the Mexicans insisted on the Rio Nueces, a hundred miles to the north. Upon annexation, the Texans’ border problem became Polk's border problem. Or so he interpreted things.

He decided to exploit the problem. He sent American troops under General Zachary Taylor into the disputed strip between the rivers. Polk's intention was that Taylor's presence would provoke the Mexicans into entering the strip. Taylor had strict orders not to back down from any confrontation. Polk would claim that American territory had been invaded; if hostilities broke out, he would claim that Mexico had started them.

Taylor marched into the disputed zone, parading his men up and down in plain view of the Mexican forces on the south bank of the Rio Grande. The Mexicans refused to rise to the bait. Polk in Washington monitored the messages from Texas, hoping to learn that fighting had begun. No violence was reported.

In frustration Polk drafted a war message for delivery to Congress. He trumped up minor grievances into unforgivable affronts to American honor. He prepared to send the dubious document to the Capitol.

At the last moment, the news Polk had been waiting for arrived. A company of Mexican soldiers had tangled with the Americans on the north side of the Rio Grande. Several Americans were killed.

“American blood has been shed on the American soil," Polk bellowed in a new message he quickly cobbled together. Congress had no choice but to declare war.

Congress did declare war, but the decision was far from unanimous. Polk's critics accurately accused him of provoking the attack; they noted that there was nothing in the strip between the rivers worth fighting over. Freshman congressman Abraham Lincoln of Illinois demanded information on the specifics of the attack. Polk blew Lincoln off.

Ulysses Grant, a young officer who saw his first action in Mexico under Taylor, served gallantly but skeptically. "With a soldier the flag is paramount," he told a journalist decades later. But sometimes a soldier should heed the inner voice. “I know the struggle with my conscience during the Mexican War. I have never altogether forgiven myself for going into that. I had very strong opinions on the subject. I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign. “

The qualms of the skeptics were lost in the excitement of the victory the war produced. Two years after the skirmish on the Rio Grande, Mexico signed a peace treaty that ceded California and New Mexico and acknowledged American authority over Texas.

Unknown to the negotiators, a week before the exchange of signatures a carpenter in California made a discovery that would increase the value of California immensely. James Marshall stumbled upon a gold nugget in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

As always, enjoy the historical newsletters.

Poor Abe Lincoln- pestering Polk over an illegal war. By the time his single term was up, patriotic fervor over the victory ran him out of office.

Imagine an alternate universe where Mexico was wishing to join NATO. The U.S. would have been sanctioned and world opinion would have been pro-Mexico and anti-Polk. Sound like Putin and Russia vis-a-vis Ukraine?