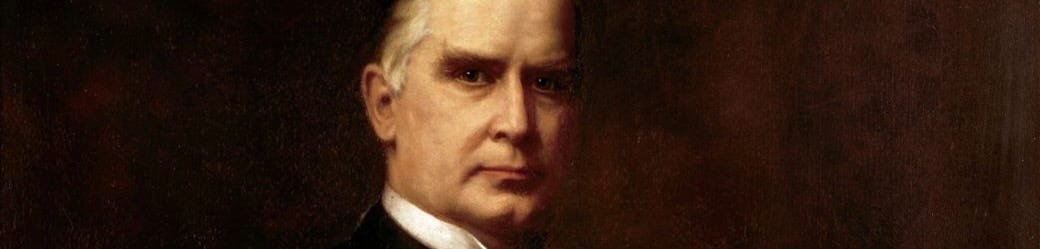

William McKinley had done his best to avoid war against Spain. “I've been through one war,” he said, referring to the Civil War. McKinley had served with an Ohio regiment at the gruesome battle of Antietam. “I have seen the dead piled up, and I do not want to see another."

But others in his Republican party wanted war against Spain. Some couched their bellicosity in terms of liberating Cuba, Spain’s most important remaining American colony, from Madrid’s misrule. Others cast it as part of an ambitious foreign policy suited to an increasingly wealthy and hence powerful nation.

The war hawks pushed hard against McKinley. Leonard Wood was an army doctor and the president’s physician, as well as an advocate of war. Theodore Roosevelt, the assistant secretary of the navy, was Wood’s friend and fellow conspirator. McKinley would joke with Wood, on the latter’s visits to the White House: “Have you and Theodore declared war yet?” Wood didn’t laugh. “No, Mr. President,” he replied. “But we think you should.”

The agitation of the war hawks compelled McKinley to send a battleship, the Maine, to Cuba to register America’s concern. When the ship blew up in Havana harbor, killing hundreds of American seamen, the war hawks blamed Spanish saboteurs and demanded war. The explosion was probably an accident—such mishaps were a regular occurrence on steamships powered by coal, which produced explosive dust—but the war hawks wouldn’t hear of it. McKinley bent to their demands and requested a declaration of war, which Congress supplied.

The war went swiftly and, from the American perspective, successfully. John Hay, the sardonic secretary of state, called the conflict a “splendid little war”; most who heard of the remark took it at face value.

The great surprise of the war was that it ended with American forces in occupation of Manila, the capital of the Spanish colony of the Philippines. Few Americans had connected the troubles of Cuba with that other Spanish colony on the opposite side of the globe. But Roosevelt did, and he sent orders to the American naval commander in the western Pacific to attack the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay on the outbreak of war. The commander, George Dewey, did so and won a swift victory. When the fighting ended, the Americans were still there.

McKinley had to decide the Philippines’s fate. He later explained his options to a group of Protestant clergymen. “When I realized that the Philippines had dropped into our laps, I confess I did not know what to do with them,” the president said, “I sought counsel from all sides, Democrats as well as Republicans, but got little help. I thought first we would take only Manila; then Luzon; then other islands, perhaps, also.”

He didn’t like any of the possibilities. He didn’t want America to become a colonial power, like the British and the French and the Spanish. But he wasn’t sure America could just steam away from the Philippines and leave the people of the archipelago to fend for themselves.

“I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight,” McKinley continued. “And I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night. And one night late it came to me this way—I don't know how it was, but it came: First, that we could not give them back to Spain. That would be cowardly and dishonorable. Second, that we could not turn them over to France or Germany, our commercial rivals in the Orient. That would be bad business and discreditable. Third, that we could not leave them to themselves. They were unfit for self-government, and they would soon have anarchy and misrule worse than Spain's was. And fourth, that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them and by God's grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died.”

McKinley’s conclusion cured his insomnia. “I went to bed and went to sleep, and slept soundly. And the next morning I sent for the chief engineer of the war department, our mapmaker, and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States. And there they are and there they will stay while I am President.”

McKinley might have embellished his epiphany in telling it to the ministers. Or the minister who recorded the interview might have embellished in the retelling. But the essence of McKinley’s message was straightforward. For America to leave the Philippines might make the Filipinos worse off than before. The Germans might snatch them up, or the country might dissolve into civil war. Better, thought McKinley, for America to stay and govern the Philippines, providing instruction in self-government and much else. His comment about Christianizing the Filipinos was gratuitous; most were Roman Catholics after centuries under Catholic Spain.

Tellingly, McKinley didn’t consult the Filipinos themselves. Some of them protested their annexation by the United States, launching a bloody war of resistance. The effort failed on the battlefield but turned Americans against imperialism. Before long even Theodore Roosevelt, by then president, concluded that McKinley’s nighttime vision, if vision there had been, had pointed America in the wrong direction. Soon Republicans and Democrats alike were trying to figure out how to get the United States out of the Philippines. World War II postponed the American departure, but in finally came in 1946.