Abraham Lincoln spent much of the summer of 1862 hiding out in the telegraph office of the war department. He said it kept him close to reports from the battlefront. But it also kept him out of public view at a time when he was wrestling with a central question of the war: what role did slavery play in the conflict? And what if anything should he do about it?

From the start of the war, Lincoln had said the fight wasn’t about slavery. Rather it was about the Union. The eleven Confederate states asserted a constitutional right to leave the Union. Lincoln denied that right, and he backed his denial with the Union army. If the Confederate states abandoned their attempt to break up the Union, they could retain the institution of slavery within their borders, just as the four slave states that had not joined the Confederacy retained slavery. If the rebel states abandoned slavery but persisted in their attempt to leave the Union, Lincoln would persist in his military effort to stop them.

He made his position explicit in an open letter to Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune. “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery,” Lincoln said. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

In private, Lincoln realized that the question was more complicated. Lincoln's war was about secession, but he realized that secession was about slavery. It wasn’t inconceivable that some state at some point would have tried to secede over some issue other than slavery, but this secession at this time had been prompted by southern fears for the future of slavery in a Republican-ruled country.

Moreover, slavery had become a tactical issue in the conduct of the war. Slaves formed the backbone of the labor force of the Confederacy. They didn't fight in the Confederate army, but their labor freed others to fight. And Confederate slaves had begun fleeing their plantations to cross the battle lines and take refuge with Federal troops. By law, Lincoln should have insisted that they be returned to their legal owners. But when those legal owners were rebels, such a policy undermined the Union war effort.

Lastly, Lincoln's public agnosticism on slavery tempted Britain to extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy. Britain had declined to do so thus far, chiefly because, having abolished British slavery decades earlier and staked out a moral position against slavery in general, the British government didn't wish to be seen as siding with the slaveholders of the American South. Yet precisely because Lincoln was saying the war was not about slavery, the British saw little to choose morally between North and South. They might as well follow their commercial interests and recognize the Confederacy. Lincoln knew this would be a disaster for the Union; he must prevent it at any cost. But how? And when?

On each visit to the telegraph office that summer, Lincoln would unlock a drawer that held paper and pen. He would write a bit, and then think a bit longer. He would write more, and think more. He would put the paper and pen back in the drawer and lock it. He would return the next day, or a few days later, and repeat the process. He told no one what he was writing and thinking about.

He tipped his hand only in late September, following a bloody battle at Antietam, Maryland, where Union forces turned back an invading Confederate army. He revealed to his cabinet that he had been writing a proclamation to free the slaves in the Confederate states.

This was less than the most ardent opponents of slavery were demanding. They wanted the abolition of slavery in all the states.

Lincoln declined to go that far. He didn't think he possessed the constitutional authority to abolish slavery entirely. His proclamation justified emancipation of Confederate slaves as a war measure, taken on his authority as commander-in-chief. He was not at war with the four slave states that hadn’t seceded, and he wasn't sure his authority as commander-in-chief sufficed there. Besides, a proclamation freeing the slaves in the border states might prove counterproductive, driving those states into the Confederacy. Maryland and Kentucky were crucial to Union strategy; to lose them might be to lose the war.

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863. Yet even then his words were only words, and would remain only words while the Confederate states were beyond Union control. All the same, no more fateful words have ever been spoken or written by a president. Lincoln's proclamation converted a war about the Union but not about freedom for slaves into a war about the Union and about freedom.

In the four score and seven years since the Declaration of Independence, Americans had grappled with the problem of slavery within a republic, and they had failed to reach a solution. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation brought a solution suddenly into sight. All that remained was for the Union army to win the war.

RE: "From the start of the war, Lincoln had said the fight wasn’t about slavery." Had there been CNN and MSNBC back then, I suspect Lincoln would have been excoriated the way Nikki Haley was when she fumbled her response about slavery and the Civil War.

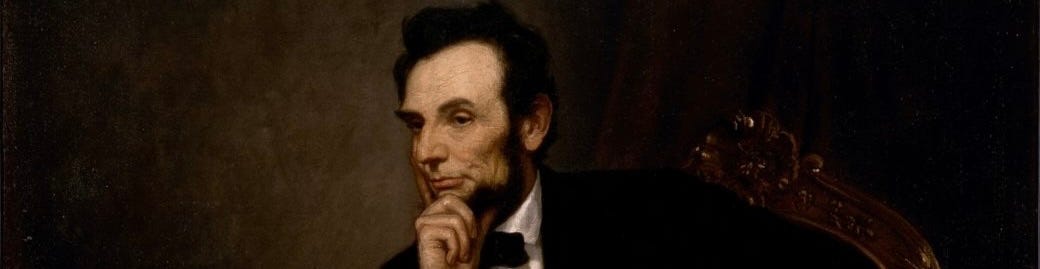

His fateful decision on the slavery issue became one of the defining moments of his Presidency.