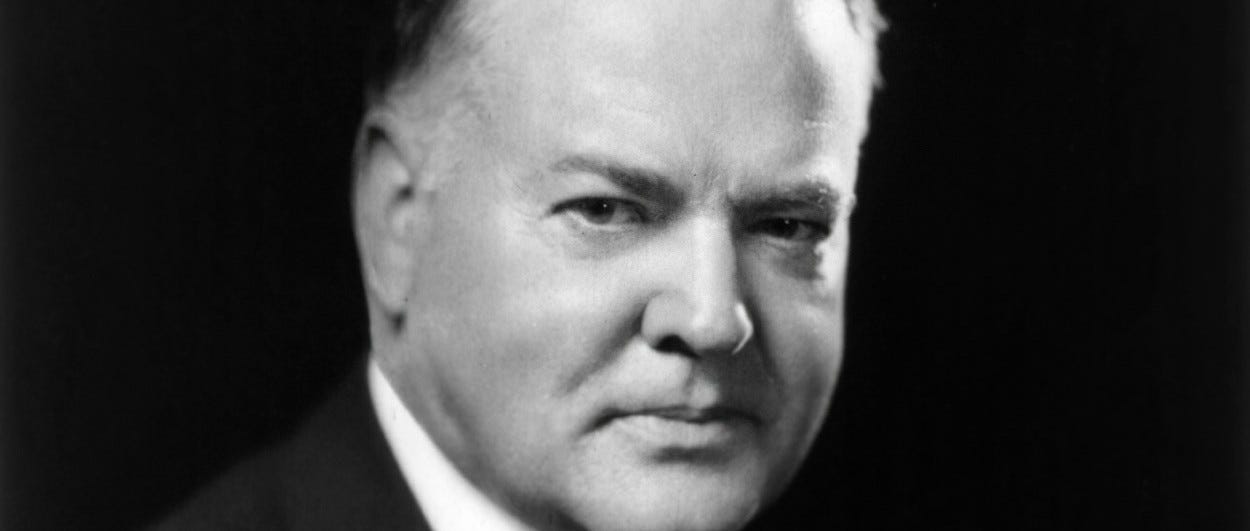

If timing isn't the most important thing in a successful life, there aren't many things more important. Herbert Hoover would have been a great president if elected in 1920. Had he presided over the boom of Roaring Twenties rather than serving merely as secretary of commerce, and had he exited at the beginning of 1929, his name would have become a watchword for national prosperity. Instead it stuck in public parlance as the generic name for shantytowns filled by the unemployed and homeless: Hoovervilles.

The stock market crash of 1929 was not Hoover's fault. Nor could he have done much about the spread of the distress from Wall Street to the larger economy. Presidents are powerful, but their powers don't include the ability to turn the American economy around. The condition of the economy is the sum of many millions of individual decisions by individual men and women. These men and women can't be dictated to by a president. They can be inspired and reassured, but in the end they make up their own minds.

Nor was Hoover gifted in the arts of inspiration and reassurance. An orphan who made his fortune by his own intelligence and determination, he tended to think, even if he did not always say, that misfortune was at least partly the fault of the unfortunate. This belief wasn't exactly wrong, but neither was it the whole story. Millions of Americans lost their jobs, their homes, their life savings during the Great Depression through no fault of their own.

Among the sufferers were veterans of World War I who had been promised a pension bonus for their service on behalf of the nation. The depression didn't hit them harder than it hit other parts of the population, but they had a collective consciousness many other groups lacked. The jobless and homeless among them compared notes, organized and marched to Washington to plead their case to Congress and the president. Their principal plea was simple: early payment of the bonus they had already been promised. The money was going to be theirs in any case; why shouldn't they receive it now when it could do them the most good? In the process the payment would give a boost to the economy as a whole.

Hoover couldn't make the decision alone; presidents aren't czars. Yet he had scope to shape the decision. What should he do?

He wasn't hard-hearted. He understood that the vets, who were being called the Bonus Army, were in a tough spot. He appreciated the moral claim they had on the country, for which they had risked their lives during the war. He agreed that early payment of the bonus would have a positive effect on the economy.

Still he hesitated. He thought people should look to themselves, not to government, when times got rough. Individualism had made America great; individualism would continue to make America great if government meddling didn't derail it. Yes, the vets had given a great deal to the country, but so had farmers and factory workers and teachers and nurses and many others. How could government choose among them?

There was something else that bothered Hoover. Most of the vets were honest men devoted to the national interest. But mingling among them were radicals bent on bringing America down. Some were outright communists; others were anarchists. These wreckers were preaching their noxious gospel to unsophisticated men trained in the use of arms. Of such designs were revolutions made. Hoover was by no means the most conservative person in America or even in the Republican party. But he was as anti-revolutionary as Americans came. Once he caught a whiff of revolution from the campfires where the Bonus Army had bivouacked near the Anacostia River, he set his face against the vets and their cause.

Hoover's top general, Douglas MacArthur—a veteran of World War I himself—was even more anti-revolutionary than the president. After Congress rebuffed the vets’ petition for early payment and they refused to disperse, MacArthur persuaded Hoover that force was necessary. MacArthur personally led a column of soldiers against the vets, scattering them—and the wives and children who had accompanied some of them—and destroying their camp. In the confusion one small child died.

The operation was a military success but a political fiasco. Most of the country thought Hoover had grossly overreacted. Franklin Roosevelt, the Democratic challenger to Hoover in the approaching election, surveyed the incident and response and told a friend, “This elects me." He was right.

One of the most damaging elements of the American psyche or ethos is the myth of rugged individualism tied to Horatio Alger "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" mythology! Oddly, the whole "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" was originally satire on the "making it on your own" myth but somehow became the metaphor for just that.

As to the Great Depression and numerous other recessions and financial panics, nearly ALL can be attributed to speculations and often Wall Street greed. A mentality of deregulation pervades the nation encouraged by lobbyists to congress when addressing these issues.