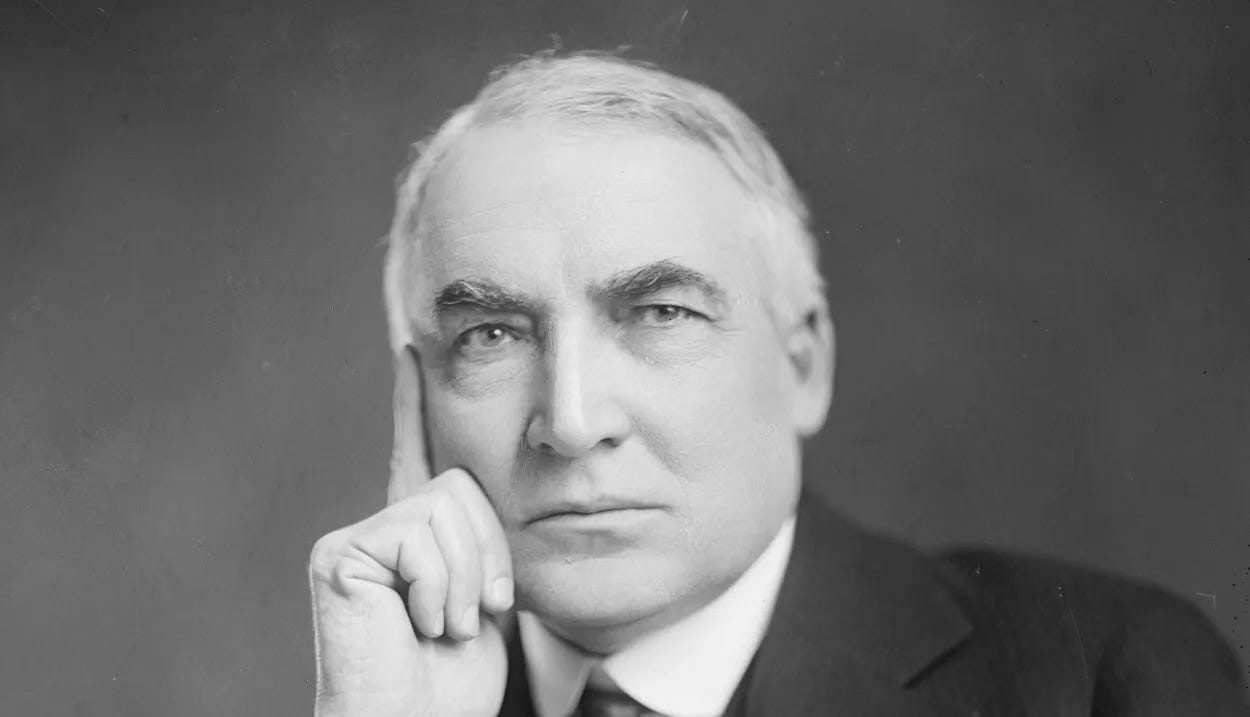

Herbert Hoover remembered a conversation he had with Warren Harding in 1923, during a tour of the West Coast, including Alaska. Hoover was secretary of commerce and Harding was president. Hoover had a reputation for unsparing honesty; Harding was known for his sketchy friends, called the “Ohio Gang” for the home state they shared with Harding. "If you knew of a great scandal in our administration,” Harding asked Hoover, “would you for the good of the country and the party expose it publicly or would you bury it?"

Hoover didn’t have to think about his answer. “Publish it,” he said. He added, perhaps to make his answer more appealing to the president: “At least get credit for integrity on your side."

Harding wasn’t convinced. “He remarked that this approach might be politically dangerous,” Hoover recalled. Hoover asked Harding to say more. “He said that he had received some rumors of irregularities, centering around Smith”—Jess Smith, aide to Harry Daugherty, the attorney general—”in connection with cases in the Department of Justice. He had followed the matter up and finally sent for Smith. After a painful session he told Smith that he would be arrested in the morning.” Smith thereupon left his office, went home, burned his papers and committed suicide.

Hoover asked Harding what Daugherty’s role in the Smith irregularities was. “He abruptly dried up and never raised the question again,” Hoover remembered. Harding was worried. “The President grew more nervous as the trip continued. Despite his natural genius for geniality, he was now obviously forcing gaiety. He sought for excitement from the receptions, parades, and speeches at every port, and all along the railway to Fairbanks.”

When he wasn’t speaking and glad-handing, Harding played cards. “He insisted on playing bridge, beginning every day immediately after breakfast and continuing except for mealtime often until after midnight. There were only four other bridge players in the party, and we soon set up shifts so that one at a time had some relief.” Hoover had begun the trip as a serious bridge player; the time with Harding cured him. “I developed a distaste for bridge on this journey and never played it again.”

Harding couldn’t bring himself to follow up what he had learned about Smith and investigate Daugherty and the other Ohio cronies. But neither could he put their shady dealings out of his mind. He grew more and more troubled as his party journeyed south from Alaska. “We first stopped at Vancouver on an exceptionally hot day in July,” Hoover wrote. “There were great crowds, long parades, and many receptions. The President rode through the city bareheaded in the heat. He was called upon for five different speeches. His speeches said little, but his fine faculty for extemporaneous friendly phrasing pleased people. That night he appeared very worn and tired, but he had to face another day of receptions, parades, and speeches in Seattle on July 27. Again the crowds were enthusiastic.”

Hoover thought the crowds might take Harding’s mind off his troubles. But then Daugherty showed up, apparently to defend himself or at least put the president off. Harding grew tenser than ever. He gave a speech at a stadium in Seattle. “There were sixty thousand cheering people,” Hoover said. “I sat directly behind him. When he was about half through his address he began to falter, dropped the manuscript, and grasped the desk. I picked up the scattered pages from the floor, gave him the next few quickly, and, knowing the text, sorted out the rest while he was speaking. He managed to get through the speech.” But only barely. He looked as though he was about to die.

Hoover and Harding’s physician hustled the president to his special train. They canceled the rest of his Seattle engagements and some in Portland and headed for San Francisco. They hoped Harding would rest en route.

They were met in San Francisco by a distinguished physician who diagnosed a heart attack. Confined to a bed in the Palace Hotel, Harding again seemed to improve. Not for long. “While Mrs. Harding was reading him a magazine article,” Hoover recounted, “the nurse saw he had broken out with perspiration. Throwing back the blankets, she began to bathe his chest, when she perceived that he was dying.” Florence Harding ran out to get the physicians. “The doctors could do nothing—in a few minutes he was dead,” Hoover wrote. Informed that the cause of death was another heart attack, Hoover mused, “People do not die from a broken heart, but people with bad hearts may reach the end much sooner from great worries.”

Harding’s death spared him close inquiry into his culpability in the scandals that soon surfaced. A dead man couldn’t be impeached or prosecuted. The conventional wisdom held that Harding had surrounded himself with grafters who took advantage of him. The worst of the scandals acquired the name Teapot Dome, for the Wyoming oil reserve from which oil was sold at sweetheart prices to insiders who bribed Albert Fall, the secretary of the navy. Fall went to prison for his crimes. Harry Daugherty was implicated in the Teapot Dome affair but was merely fired by Harding’s successor, Calvin Coolidge.

I know other people think differently, but Harding is my candidate for the Worst President Ever title.

Well, he just died.

Solved that problem.