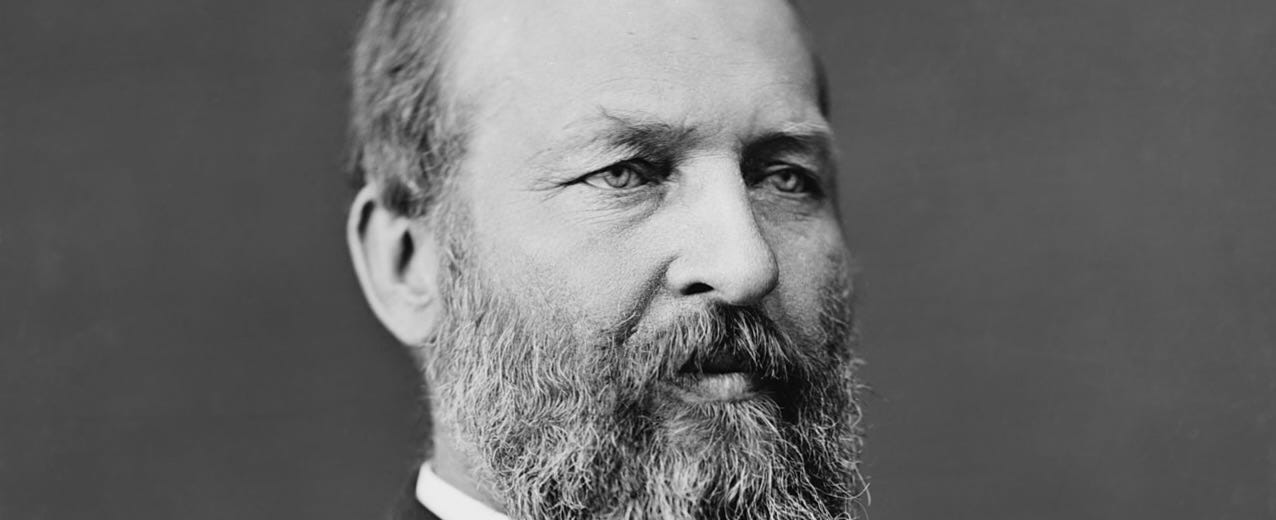

James Garfield was known to be ambidextrous and bilingual. He was said to be able to be both at the same time, writing Greek with one hand while writing Latin with the other. No firm evidence of this simultaneity exists, but the fact that it was believed by many people attested to the distinctive traits Garfield brought to his long political career—a career that might have been importantly longer had Garfield's physicians not turned a worrisome wound into a lethal one.

Garfield was as self-made as his political model, Abraham Lincoln. Garfield's father died when he was young and his mother struggled to set food on the table. Garfield learned to work and worked to learn, putting himself through Williams College in Massachusetts, where he graduated near the top of the class. He taught school and then entered politics, pausing his rise in the latter field to serve in the Union army during the Civil War. After the war he was elected to the House of Representatives, where he continued to serve until 1880.

No one had ever been elected to the presidency directly from the House of Representatives, nor has anyone since. This is partly because the skills that conduce to success in a legislature are not those that inspire voters assessing presidential candidates. The legislators must learn to compromise and to cajole; aspiring executives must appear decisive and certain.

Garfield would not have received the Republican nomination in 1880 had the party of Lincoln not become deeply split during the decade and a half since Lincoln's death. The rival factions, called Stalwarts and Half-breeds, loathed each other as least as much as they disliked the Democrats. At the 1880 Republican convention, the factions fought to a standstill. Neither side would yield to the other. Mostly out of exhaustion, they turned to Garfield, who during his congressional career had learned to get along with members of both factions.

By 1880 the Republicans had run through nearly all the political capital they won defending the Union under Lincoln. The Democratic nominee, Winfield Scott Hancock, was a Union general presented during the campaign as the logical heir of Ulysses Grant. Garfield barely defeated him, twenty years after the first election of Lincoln.

Americans, including Garfield, remembered that Lincoln had been assassinated. But most Americans, again including Garfield, deemed Lincoln's murder by John Wilkes Booth an artifact of the Civil War. The war was long over; no one would have cause to kill a president now.

Which was why Charles Guiteau had such an easy time approaching and shooting Garfield at a Washington train station. Guiteau was disappointed at not having received a job in the Garfield administration; he seems also to have been mentally deranged.

One bullet wounded Garfield in the arm; another penetrated his back. The latter was the more serious, raising the likelihood of internal bleeding and infection.

Not uncommonly in those days, the doctors of gunshot victims left the bullets inside their patients. If the bullets and the infections they produced didn't prove fatal in the first few days, the bullets typically became encysted and posed little continuing danger. Andrew Jackson spent the last three decades of his life carrying in his person bullet fragments from a shooting scrape.

But Garfield's doctors thought they could do better. A president in the late nineteenth century deserved better. They poked and probed to find the bullet that had entered his back, and they did so with unsterilized fingers and instruments. Joseph Lister in Britain was preaching the gospel of antisepsis—keeping germs away from open wounds—but his philosophy hadn't caught on in America.

The probing probably killed him. Garfield's condition improved before growing worse. He ran a fever and lost weight. Complications afflicted his heart. Very carefully he was taken to the New Jersey shore to escape the heat and humidity of Washington's summer. The change of scenery brought no change of condition. At length he died, 79 days after his shooting.

From that time forward, the health and medical care of presidents became a national priority. Yet it clashed with doctors’ regard for their patients’ privacy—and their perception of the national interest. Grover Cleveland’s doctors employed subterfuge and secrecy while they removed a tumor from his mouth; the secrecy reflected Cleveland’s concern that news of the cancer and of the surgery might roil financial markets. Cleveland was a hard-money man; his vice president was an inflationist. Franklin Roosevelt's physician perjured himself ahead of the 1944 election, pronouncing the fourth-term-seeking president fully fit for the job of bringing World War II to a successful close. Persons close to Roosevelt weren’t surprised when he collapsed and died three months into his new term. John Kennedy's doctors kept mum about the numerous ailments America's youngest elected president battled; for the Russians to know would tempt them to something rash.

In time the veil was lifted on presidents’ health. The president's medical file was treated as an open book, or at least a book that ought to be open. The characteristic of secrets is that those on the outside often don’t know what they don’t know.

The Twenty-fifth Amendment mandated constitutional light on the matter of presidents’ health. Three presidents—Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush and Joe Biden—voluntarily and temporarily handed off power to their vice presidents during surgery. The part of the amendment calling for an involuntary transfer of power on account of presidential disability has not been invoked.

An excellent book (like Brands' books: scholarly yet "readable") is _Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President_ (2011) by Candice Millard.