We all say things we later regret. But few of us do so on a national stage in front of a television audience of tens of millions of people, in memorable language intended to make reneging nearly impossible.

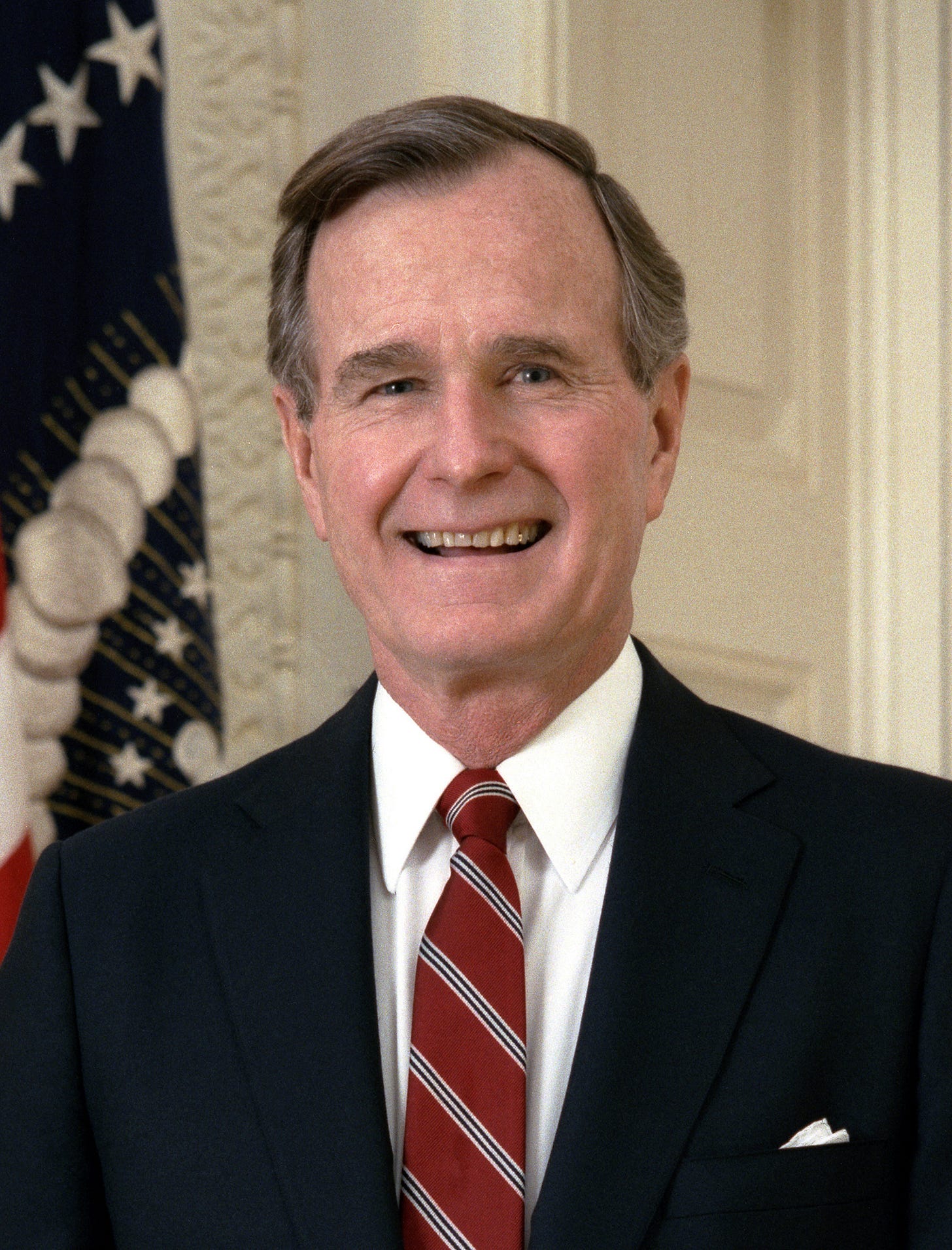

George Bush (who didn't have two middle initials customarily added to his name until another George Bush became president) was a traditional Republican who had the misfortune of living through the Reagan revolution in American political economics. For generations Republicans had been the party of fiscal responsibility, insisting on balancing the federal budget. Reagan entered office as a budget-balancer, but during his first term he got Congress to make tax cuts without corresponding cuts in spending. The cumulative result during his presidency was a doubling of the federal debt, in real terms. Put otherwise, Reagan ran up as much debt as all the presidents before him combined.

Bush, as vice president, held his tongue and bided his time. After eight years of loyal silence, he had reason to expect the Republican nomination in 1988. Given Reagan's continuing popularity, this seemed equivalent to election. Bush’s rivals, however, questioned his commitment to the party’s new orthodoxy on taxes: that they must never, ever be increased.

With the presidency almost in his grasp, Bush silenced his scruples and took the pledge. In his speech to the Republican convention he distinguished himself from the Democratic nominee, Michael Dukakis, who had said he would raise taxes only as a last resort.

“My opponent won't rule out raising taxes,” Bush said. “But I will. And the Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I'll say no, and they'll push, and I'll say no, and they'll push again, and I'll say, to them, ‘Read my lips: No new taxes.’”

The partisan audience roared. Bush swept into office.

Then the hangover from Reaganomics kicked in. New projections of deficits far into the future spooked Wall Street and caused bond vigilantes to bet against the dollar. Lest their dire prophecy become self-fulfilling, Bush met with Democratic leaders in Congress to discuss a grand bargain to tame the deficit. They agreed to cut spending if he would support tax increases.

The pre-Reagan Bush would have accepted in a minute. But the no-new-taxes Bush had to think it over. If he went back on his public pledge, would he doom his reelection hopes? The never-taxers in the party would try to derail his renomination. Failing that they might back a third-party candidate.

Bush’s conscience got the better of his ambition. Convinced that the deficit danger was real, he put his signature to the grand bargain.

Two results followed. Bush lost his race for reelection in 1992, which was indeed contested by third-party candidate H. Ross Perot, who got 19 percent of the vote.

And the deficit declined. By the end of the decade it went all the way down to zero.

In retirement Bush had the satisfaction of knowing he had done a good thing for his country, even if it cost him the presidency.

And he watched, likely with ambivalence, as his son, elected president in 2000, proceeded to blow up the grand bargain and set the deficit soaring again.

Few other Presidents have had their voice and mannerisms mocked in such a cutting way as he suffered from the comedians of the world.