Tariffs were to American politics in the 19th century what taxes have been since World War I. This isn't surprising, since tariffs are taxes—on imports. As a rule, manufacturers wanted a high tariff, to discourage competition from foreigners, while farmers wanted a low tariff, to reduce the cost of living. The Whigs and their successors the Republicans, the parties of manufacturers, pushed tariff rates up when they had the chance. The Democrats, the party of farmers, pulled them down.

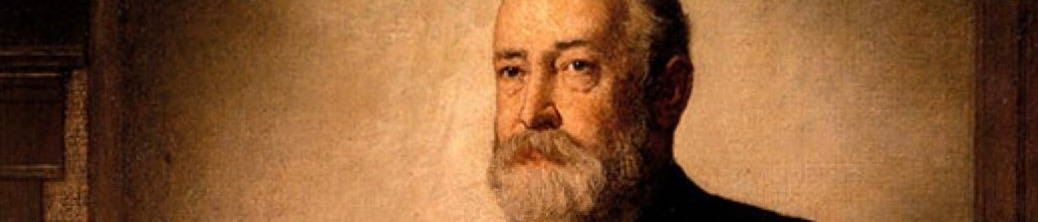

Benjamin Harrison, a Republican elected president in 1888, favored a higher tariff. But Harrison wasn't the leader of the tariff campaign. Presidents in those days deferred to Congress on tariffs and other taxes, as Article 1 of the Constitution says they should. William McKinley, a Republican from Ohio, took charge of the tariff campaign in the House of Representatives, the chamber in which, again according to Article 1, tax bills have to originate. So influential was McKinley that a successful tariff hike in 1890 came to be called the McKinley tariff.

Harrison liked the higher rates the McKinley tariff imposed on imports, and he signed the bill with pleasure. As the then-keeper of the office of the president, he was even happier with the new discretion the bill delegated from the legislative branch to the executive. Tariff schedules are enormously complicated; thousands of items have to be put into this category or that. Congress knew that it had neither the patience nor the personnel to tend to such details. It authorized the executive branch to hire the people to do the tending. The McKinley bill also granted the president authority to negotiate with foreign countries on trade—to haggle and barter over reciprocal tariff reductions.

The high rates imposed by the McKinley tariff didn't last long. The losers in the debate—farmers and Democrats—struck back in the next election, ousting the Republicans, including Harrison. They passed a tariff bill of their own, which reduced rates.

But the handoff of power to the presidency had long-term ramifications. The tariff itself became less important to American federal finance after ratification of the 16th Amendment, which allowed enactment of a federal income tax. By the end of World War I, the income tax provided the principal revenue stream for federal operations. During World War II, the United States abandoned the principle of tariff protectionism, in favor of the free trade it promoted for the next 70 years.

Yet the principle established by the McKinley tariff and endorsed by Benjamin Harrison resurfaced during the presidency of Donald Trump. In keeping with his philosophy of populist nationalism, Trump launched a trade war of tariff protection against China and other foreign countries. He did so without consulting Congress, relying instead on the authority descended from that 1890 law.

Trump was pleased to be likened to Andrew Jackson, the original avatar of American populism. He might at least have given a nod to Benjamin Harrison, whose signature on the McKinley tariff made the Trump trade war possible.

Comparing Jackson to Trump makes sense- two political outsiders who shook up the Washington establishment by being independent from them.

The founders, I thought, believed in tariffs to protect native industries until they could get their foot on the ground and sustain themselves.

Trump's tariffs made no sense whatsoever and were all about exacting retribution and appealing to a base who had no idea how the tariff's work.

The end result was farmers in the USA dumping product and being reimbursed for it by the federal government -product that they would have normally sold to China , but for the tariff war.