Talk about a tough act to follow.

Andrew Johnson was the third president to reach the White House via the side door. The predecessors of John Tyler and Millard Fillmore had died natural deaths. Johnson's predecessor, Abraham Lincoln, was assassinated. Lincoln had been controversial in life—his election triggered the breakup of the Union, and his conduct of the Civil War included jailing critics and suspending inconvenient parts of the Constitution—but in death his sins were forgiven, and he was canonized as a martyr to freedom and democracy.

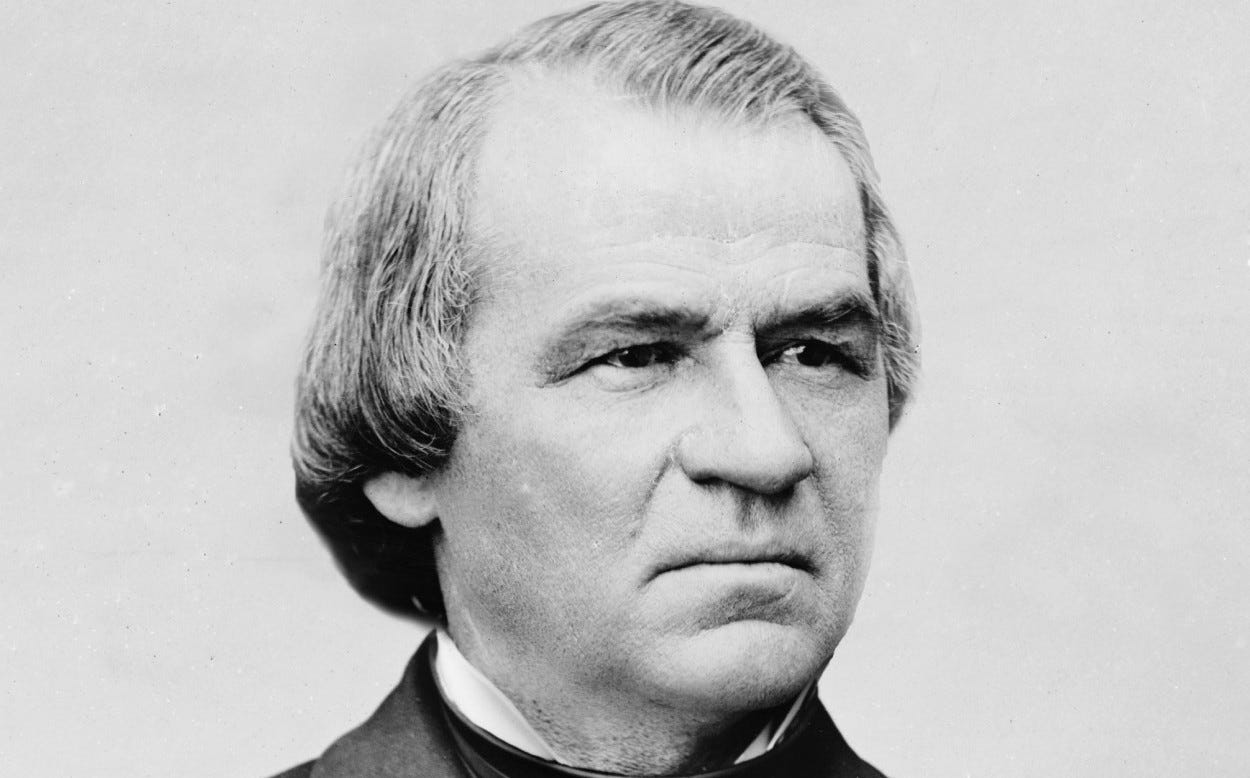

No one could have lived up to the posthumous standard of Lincoln, not even Lincoln himself, had he lived. And Andrew Johnson was no Lincoln. He was all wrong to be Lincoln's successor. He was from the wrong section: a southerner at a time when the North had just won the war. He was of the wrong party: a Democrat at a moment of Republican supremacy. He was of the wrong temperament: combative and blusterous when tact and humility were called for.

Johnson became president because he had been vice president, and he had been vice president because Lincoln wanted to show that the Union war effort was not simply a project of northern Republicans. For the 1864 election, Lincoln ousted Hannibal Hamlin, the incumbent vice president, a Republican from Maine. Hamlin had brought geographic balance to the Republican ticket in 1860: westerner Lincoln matched with easterner Hamlin. But Hamlin was not a popular figure. Lincoln said that Hamlin was assassination insurance: no one would kill Lincoln knowing Hamlin would become president. Yet Lincoln was willing to cancel the insurance policy and bring Johnson, a Unionist Democrat whom Lincoln had appointed military governor of the Unionist part of Confederate Tennessee, onto the 1864 ticket in Hamlin’s place. When Lincoln won reelection, Johnson became vice president. And he became president when Lincoln was murdered a month into his second term, a week after the end of the war.

Johnson faced major challenges. The rebellious states had to be readmitted to the Union. The former slaves had to be integrated as free men and women into the economy and polity of the South. The leaders of the rebellion had to be prevented from returning to positions of power in the states and in Congress.

A final task was more subtle but hardly less consequential. The balance between the federal government's legislative and executive branches had to be restored. The Civil War did something that would be repeated in every subsequent American war: it shifted power from Congress to the presidency. The Constitution makes the president commander in chief, giving him authority to call out the state militias, send soldiers and ships hither and yon, and commandeer private property. Lincoln employed this last power to deliver the single boldest stroke in American political history: the emancipation of slaves in rebel states. In the interest of winning the war, congressional leaders had tolerated Lincoln's power grab. But both he and they knew there would be a reckoning at war's end.

The reckoning fell to Johnson. From the moment he entered the White House, Johnson was in the crosshairs of the congressional Republicans. The particulars of his being a Democrat and a southerner simply made it easier for them to do what they would have done otherwise.

Johnson's behavior made it easier still. The new president initially vowed to deal harshly with rebel leaders. “Treason must be made odious, and the traitors must be punished and impoverished,” he declared. But in the face of the Republican campaign to recapture Congress’s lost power, Johnson backtracked. Employing the pardoning power of the presidency, he halted potential prosecution of thousands of Confederate leaders—southerners and Democrats, like Johnson.

This outraged the Republicans, especially the left wing of the party, the Radical Republicans. They determined to do something never done to a president: remove him from office by impeachment. They laid a trap, in the form of a measure called the Tenure of Office Act. The Constitution specifies that cabinet secretaries and other top executive officials must be confirmed by the Senate. It says nothing about removing such officials. The Tenure of Office Act remedied this deficiency by requiring Senate concurrence in removals.

Johnson denounced the measure, as any president would have. If the framers of the Constitution had wanted to require Senate approval of dismissals, they would have said so, Johnson argued. The measure was unconstitutional. He vetoed it.

Congress overrode the veto. Johnson put the new law to a test by firing Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war, without requesting or receiving Senate approval.

The House of Representatives voted to impeach. The case went to the Senate, which acts as the jury in impeachment trials.

If the verdict had been up to a simple majority, Johnson would have been convicted. But the Constitution requires a supermajority of two-thirds for conviction. The anti-Johnson bloc wasn't quite that large; he escaped conviction by a single vote.

The failure of the Republicans to convict Johnson placed a long hold on the impeachment power. Not for more than a century would impeachment be seriously considered again. Richard Nixon was about to be impeached as the extent of his Watergate crimes became known, but he resigned ahead of the House vote. Bill Clinton was impeached over a sex scandal but like Johnson was not convicted. Nor was Donald Trump convicted in either of his two impeachment trials.

“Johnson faced major challenges. The rebellious states had to be readmitted to the Union. The former slaves had to be integrated as free men and women into the economy and polity of the South. The leaders of the rebellion had to be prevented from returning to positions of power in the states and in Congress.

A final task was more subtle but hardly less consequential. The balance between the federal government's legislative and executive branches had to be restored.”-H. W. Brands

I realize that asking the question: “What if ...?” is a temptation in history most often best avoided. However, framed another way, the replacement by Lincoln of Hamlin as Vice-President with Johnson on his 1864 Republican ticket and, after the forces in our nation’s past brought about Lincoln’s assassination and its dynamic impact upon Reconstruction, the spirit of which seems to have lingered into the Twenty Second Century, has been in my thoughts for quite a while. I think about it every 4-year election cycle when an incumbent President makes the decision to keep the existing “partner,” or to divorce and find another. Divorces of any type have repercussions all the consequences of which cannot be foreseen or intended.

It occurs to me that vice- presidential decision by incumbent Presidents is less focused upon by chroniclers of American history than it rightfully deserves. The selection of a successor to royal or imperial power has been a major force in world history.

That said, I also think on whether my thoughts on vice-presidential selection itself may be influenced by regionalism and having lived all my life in some part of Texas (except for a year in Selma, Alabama). Although I was not alive at the time of the 1940 Democratic Convention, when Franklin Roosevelt, for his unprecedented third term, decided to replace John Nance Garner as his running mate with Henry Wallace, I have parents and grandparents who were, the latter having been in attendance.

Roosevelt’s 1940 decision was as much a part of the tipping of the scales in the delicate “balance between the federal government's legislative and executive branches” back in the direction of what it had been under Lincoln, as Lincoln’s 1864 decision had been on that balance the other way.

Interesting concept in the Tenure of Office Act. Doing a quick google finds it was repealed entirely twenty years later after SCOTUS ruled on a similar issue which indicated they may consider the TOA unconstitutional. I think Johnson's attitude in this regard was correct. Senate confirmation required, but not removal. A chief executive must have confidence in his cabinet and one kept there by the legislature is effectively putting a "plant" in the cabinet.

One also wonders about the "acting" official and legitimacy. If I recall correctly, there is a law which spells out which officials must have Senate confirmation. Per the scholarly paper I link below, it points out that 'acting' positions go back even to the early days of the Republic. In modern times our several recent presidents relied on acting officials- usually due to the short notice nature of the confirmed office older's departure (death or resignation). One impediment to confirming an official is the Senate itself which is now taking six months to get approvals through and finalized!

But I think the bigger issue is INTENT. Previous presidents (Bush, Clinton, Obama, GWBush) had to rely on putting acting officials into place because of both short notice and Senate foot-dragging. But Trump was a departure there. He literally didn't want to deal with Senate confirmtions. He even stated "I like acting. It gives me more flexibility. Do you understand that? I like acting. So we have a few that are acting. " The intent appeared to bypass the Senate for as long as possible.

https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3249&context=articles