We’re number two!

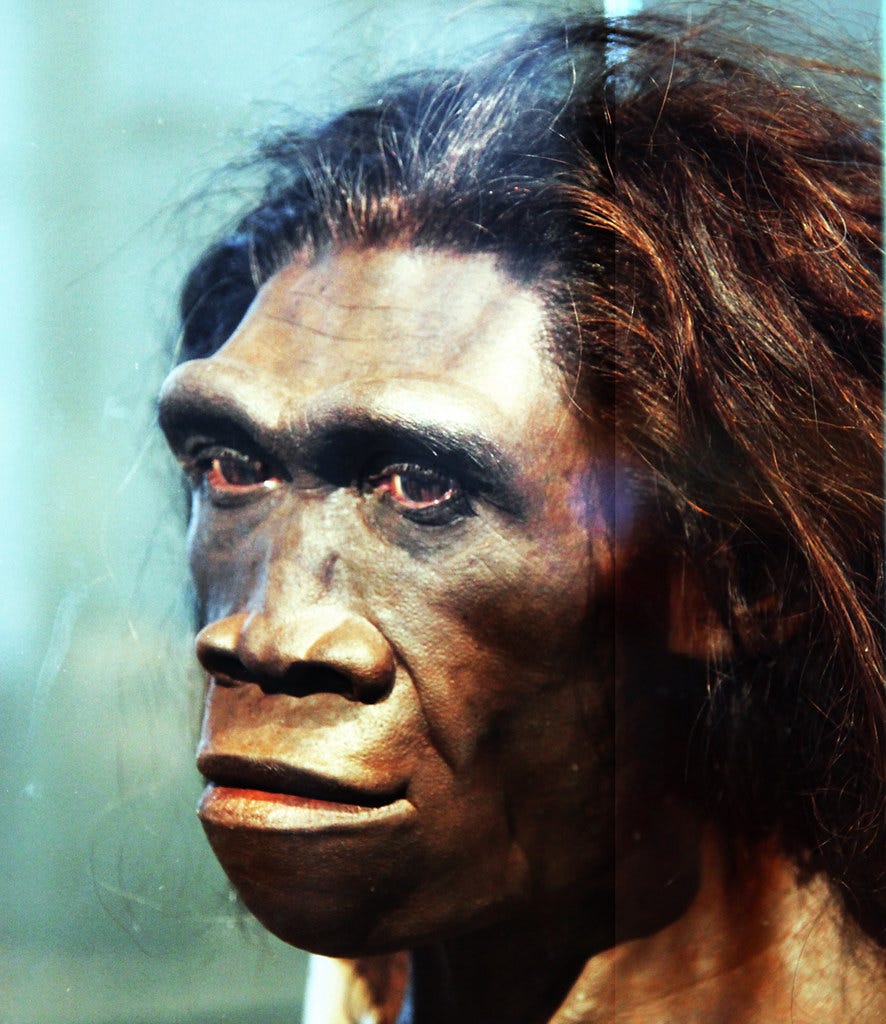

Behind Homo erectus

We humans spend a lot of time congratulating ourselves. Some of us do so as individuals, noting the accomplishments that make us stand out from those around us. Others take comfort in the greatness of the collective: our team, our country, our race. Aggrandizing one’s favorite team is still acceptable, sports being recognized—by most people, away from the stadium—as innocuous escapism. Boasting about one’s country is admirable patriotism to those who concur in its virtue and obnoxious jingoism to those who don’t. Puffing up one’s race carries historical baggage and is now shunned in polite company.

On a larger scale, we humans as a species have been patting ourselves on the back from the moment we first stood on our hind legs and thereby freed an appendage for the patting. Not every origin story was as explicit as Genesis in according humans “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth,” but most granted pride of place to the species telling and hearing the origin story.

Charles Darwin proposed a different kind of origin tale, but it ended the same way: with humans at the center of creation—or evolution. To be sure, his Origin of Species talked of species generally, but what grabbed all the attention was his follow-up The Descent of Man. When he said that the beaks on finches changed over time, many readers yawned, but when he said that ancestral apes gave rise to humans—to us!—he touched off a firestorm that still hasn’t been entirely contained.

Even among those who have accepted Darwin’s model, there has long existed a a cottage industry in identifying traits that make us different—usually meaning better—than other animal species. Tool-making was a marker that held for a long time, until chimpanzees were found to be cracking nuts with rocks and using twigs to fish termites out of their mounds. Language was another uniquely human talent, until whale songs were heard to have syntax and other characteristics of language. Crows were found to be able to count, depriving us of arithmetical uniqueness. Self-awareness lost its cachet when elephants recognized themselves in mirrors.

Yet even if those non-human species could mimic us at the margins, we Homo sapiens still congratulated ourselves on being an improved edition of our hominid ancestors. Anthropologists devoted effort and patience to finding evidence of the first time human-like creatures used tools, produced art, buried their dead, invoked the divine. Reputations were made by those documenting when we became human—when we became creatures who looked and acted like us. In a more candid era than ours, the anthropologists juxtaposed the “primitiveness,” “barbarism” and “savagery” of the low-browed, lumbering forms they conjured from the fossil record, against the more intelligent and refined beings who displaced them. We were the standard our ancestors were measured against; on their best days, in their best millennia, they always fell short.

This judgment remains common and largely noncontroversial. “De mortuis nihil nisi bonum”—Speak no ill of the dead—doesn’t extend to the extinct. Yet before we sprain that arm we’re patting ourselves on the back with, we should consider the case of Homo erectus.

"Upright man" first appears in the fossil record around two million years ago. He and she show up across Eurasia, from the Iberian peninsula to the island of Java. They walked pretty much like us and had body proportions like ours. Their voice boxes were different from ours, so it's unclear if they had spoken language we would recognize as such. But they certainly communicated effectively, for they hunted large game that no single one of them could have taken down alone. They had stone tools and possibly used fire. They apparently divided up the labor that kept them alive, with men, the more expendable, getting riskier jobs like hunting and war, and women watching the kids and gathering food items that couldn't fight back. They weren't as smart as us, if brain size is a reliable gauge. They didn't discover agriculture or build cities.

But they lasted—as a species—a long time: at least 1.9 million years.

One measure of species success is population size. We Sapiens have been enamored of this at least since God told Noah and his sons to "be fruitful and multiply." In the modern era we employ GDP as a proxy for population in the growth-is-good philosophy. In numbers and accumulation of stuff, we Sapiens have Erectus beaten badly.

But there are other measures of species success, such as endurance on earth. On this score we're far behind. We first show up in the record around three hundred thousand years ago. We didn't do much that marked us as special until twenty or thirty thousand years ago, and even after that we didn't start multiplying dramatically until a few hundred years ago.

Conceivably our run as a species will eventually match that of Erectus. But given our ingenuity in devising technologies that could destroy us, this is no sure thing.

Until then, let's take that back-patting hand, put a beer or other beverage in it, and toast Homo erectus, the most durable of our genus.

Great book on this topic called LAST APE STANDING by Chip Walter.