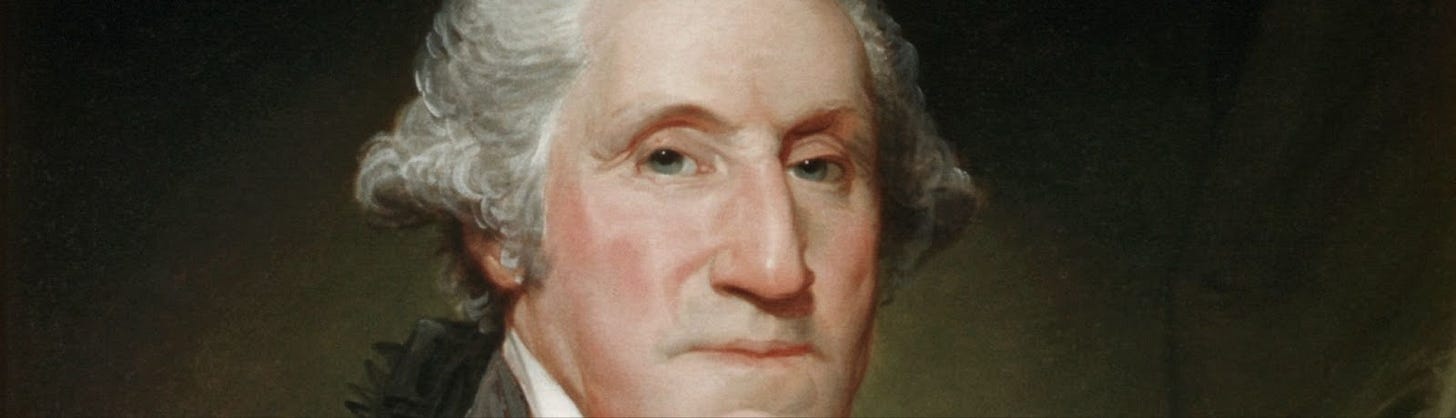

Washington's secret

You never forget your first

Since the middle of the 20th century historians of the American presidency have agreed that three chief executives stand above the rest: Washington, Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt.

Lincoln's indisputable claim to fame is that he held the Union together against southern secession and ended slavery. Roosevelt's is that he guided America through the Great Depression and led democracy to victory during World War II.

Washington's hold on the historians is harder to explain. He commanded the American army that defeated Britain during the Revolutionary War, but of course that was separate from his presidency. He fought no wars as president. Indeed he kept aloof from Europe's wars, proclaiming neutrality for the United States in the bitter struggle between Britain and France. It was a wise move and good for the country, but his proclamation was of dubious constitutionality. Anyway, presidents don't get high grades for merely avoiding errors.

He didn't guide the country through a depression. Depressions didn't exist in those pre-industrial days. The closest thing to secession he had to deal with was a rebellion among farmers in western Pennsylvania protesting a whiskey tax. They were dispersed by a show of force. Washington did nothing about slavery.

He’s often applauded for retiring after two terms. His action set a precedent for his successors and thereby ensured timely rotation in office. If not for Washington, America’s chief executives might have become presidents for life.

Yet Washington’s motive for retiring had little to do with de facto term limits. He left the presidency because he was fed up with the job. He had accepted the office, which in those early days was much less a prize than it would become, out of a sense of obligation. James Madison had talked him into attending the constitutional convention of 1787, claiming his presence was essential to its success, and that the success of the convention was needed to save the Union from dissolution at the hands of rebels like Daniel Shays. After the convention, Washington was told by Madison and many others that his presence at the head of the new government was essential to ensure its successful launch.

Washington was talked into a second term by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, who couldn’t agree on anything else. It was to keep their infighting from destroying the government that Washington consented to stay on. They left the government but the fighting grew worse. The insults targeted even him—George Washington! He hadn’t signed on for this, and he wouldn’t stand for it.

He never felt more relief than on leaving. “A solemn scene it was indeed,” John Adams wrote to wife Abigail of the transfer of power from Washington to himself at Adams’s inauguration. “And it was made more affecting to me by the presence of the General, whose countenance was as serene and unclouded as the day. He seemed to me to enjoy a triumph over me. Methought I heard him think: Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which of us will be happiest.”

Washington left a message for his compatriots. He warned them against the “baneful effects of the spirit of party,” saying, “A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.” During his second term, the emerging parties had taken opposite sides in the Anglo-French war. Washington extended his warning to such foreign attachments. “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” he said.

Washington’s performance as president was perfectly creditable. But top three? Where does that come from?

First from the fact that presidents during the first century under the Constitution were consistently unmemorable. This was by the design of the Constitution itself, which in Article I accords initiative in governance to the legislative branch rather than the executive. A few presidents before 1900 stood out: Washington for being first, Jefferson for buying Louisiana, Jackson for threatening war against South Carolina in the nullification crisis, Lincoln for the Civil War. But that's about it. And so until the twentieth century, Washington had little competition for ranking high.

Second from Washington’s remaining above the partisan fray. Washington disliked partisanship. So did—and do—most Americans. But unlike most American politicians, Washington could stay out of the scrum. His presidency was a victory lap for his wartime leadership. His ambitions had been sated before he took office. His successors had no such luxury. Their ambitions required them to pick a side and play the game. They diminished themselves, compared with Washington, in the process.

Third from the fact that Washington was the first president, and that the experiment he launched proved a great success. Columbus wasn’t smarter or braver than every other sea captain of his day, but he got to America first and so is remembered for that. In fact, the Columbus case is especially instructive. Leif Erikson got to America before Columbus, but his colony didn’t succeed. If the American government under the Constitution had failed, Washington would be a footnote like Leif.

Moreover, the fact that Washington was first also made him the last. The first skier down a mountain after a snowfall is the last to carve the untouched powder. Whoever had been the first president would have set precedents simply by being first. Washington gave an inaugural address, which isn’t mentioned in the Constitution; presidents ever since have been giving them. Washington grouped his advisers into a cabinet; so have his successors. Washington disdained fancy titles, preferring “Mr. President,” which has been good enough for every president who followed him.

Joe Biden is America’s forty-sixth president. There will be a forty-seventh and others beyond that. The numbers have long since run together. As the list lengthens, the first president will stand out all the more.