“Since my last,” George Washington wrote to his brother John, “we have arrived at this place, where 3 days ago we had an engagement with the French.” The year was 1754, and Washington was twenty-two years old. The place was the Great Meadows, a natural open area in what would become southwestern Pennsylvania. Its significance at the time was that it was located halfway between the Cumberland River and the Forks of the Ohio River. The Cumberland was securely British, but the Ohio was up for grabs with the French, who then controlled Canada. Washington commanded a party of Virginia militia dispatched to stake Britain’s claim to the Ohio and the country it drained.

Washington had been to Ohio and knew the territory. On the strength of this experience he had received his commission in the militia, despite his youth. He had managed men, on those previous expeditions when he had surveyed land for potential purchase. But he had never led men into battle, nor been exposed to enemy fire himself.

“Most of our men were out upon other detachments, so that I had scarcely 40 men under my command, and about 10 or a dozen Indians,” Washington continued in his letter to John. The Indians were members of tribes that had thrown in their lot with the British, against tribes that sided with the French.

Washington's company bumped into the hostile Indians and French almost by accident. “Nevertheless we obtained a most signal victory,” Washington said. "The battle lasted about 10 or 15 minutes, sharp firing on both sides, when the French gave ground and run, but to no great purpose." A dozen of the enemy were killed, including Joseph de Jumonville, their commander. A score of prisoners were captured. “We had but one man killed, 2 or 3 wounded and a great many more within an inch of being shot.” Washington counted himself among the near misses.

He supposed the French would seek revenge. “We expect every hour to be attacked by a superior force.” He hoped the counterattack would be delayed at least a little. He and his men were busy preparing for the event. "We have already got intrenchments and are about a pallisado’d fort”—a timbered stockade—"which will I hope be finished today.”

Washington looked to the Indian allies. “The Mingos have struck the French and I hope will give a good blow before they have done. I expect 40 odd of them here tonight, which with our fort and some reinforcements from Col. Fry, will enable us to exert our noble courage with spirit.”

Washington signed off, “Your affectionate brother,” before appending a postscript: “I fortunately escaped without a wound, though the right wing where I stood was exposed to and received all the enemy’s fire and was the part where the man was killed and the rest wounded. I can with truth assure you, I heard bullets whistle, and, believe me, there was something charming in the sound.”

George III, learning of Washington's comment, reportedly remarked that the young colonial would have been less charmed by the sound of bullets had he heard it more often. Not for the last time, the British monarch underestimated Washington.

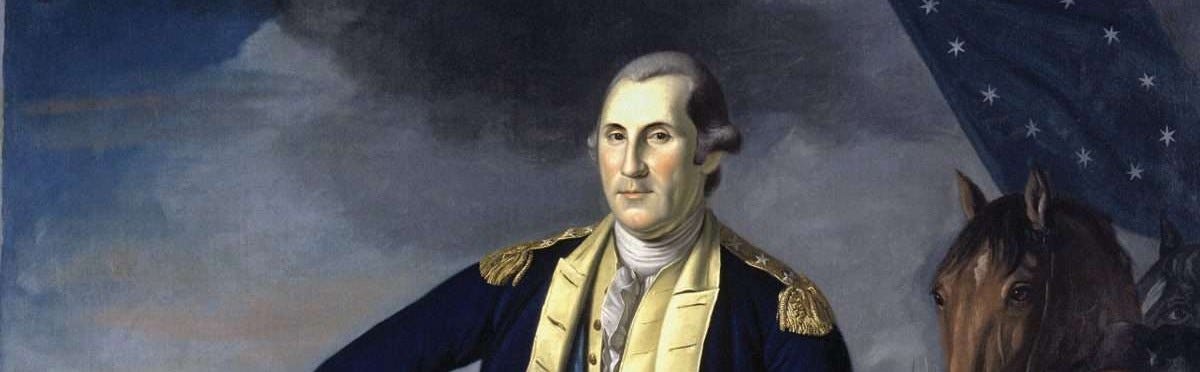

Some people, men traditionally, are born for soldiering. They never feel more alive than when at risk of sudden death. Washington was one of those, as he would demonstrate repeatedly during the next three decades. He was a tall, strong fellow, with a commanding presence. He gave orders and men obeyed them. He asked his men to be brave, but no braver than he was himself. Time and again he placed himself in the line of enemy fire. By good luck he was never killed or gravely wounded.

As he grew older and the numbers under his command increased, he learned to weigh the risks of armed conflict more soberly. But he never lost the feeling that the moment of battle was the truest test of a man, and the sound of bullets never lost its charm for him.

RE: "he [Washington] never lost the feeling that the moment of battle was the truest test of a man, and the sound of bullets never lost its charm for him," it reminds me of a line from the movie _Patton_:

"When compared to war, all other human endeavors shrink into insignificance. War - I love it! God forgive me, I love it so much." Now whether Patton actually said those words, we don't know. But Patton easily could have said it - or Washington.

...and eventually, he would command an entire nation as the first President of the United States, in a fashion not far removed from his military bearing. With the same level of respect given in return.