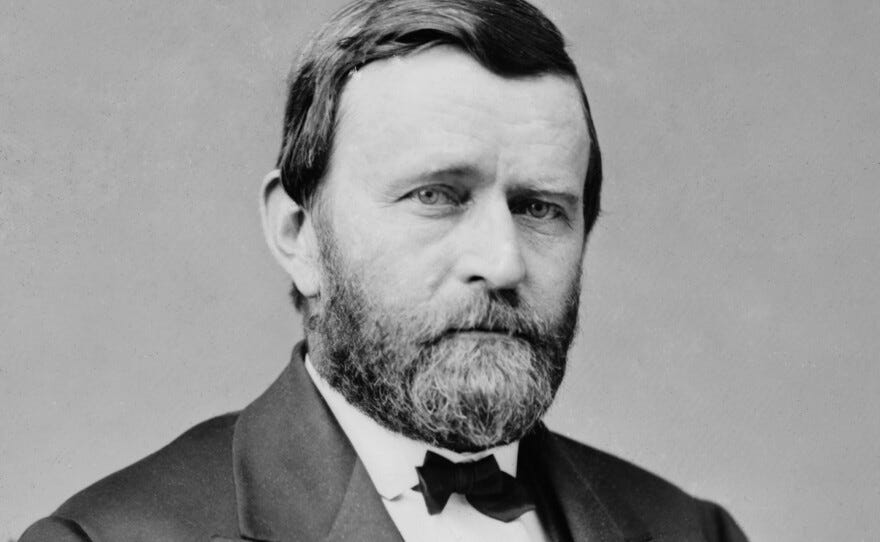

If Ulysses Grant had been better at business he might not have been so good at war. If he hadn't been so good at war he never would have been president.

Grant tried various businesses between the Mexican war and the Civil War but made a mess of them. The coming of the latter rescued him from invisible mediocrity. His genius for war rendered him irresistible to Republican politicians after Appomattox and to voters after he let the politicians talk him into running for president.

As president he found himself back in business, after a fashion. The financial demands of the war had prompted Congress to issue paper money for the first time. The greenbacks, as the legal tender notes were called for their green ink, circulated alongside notes that were redeemable in gold. The greenbacks were perceived as less secure and therefore less valuable than the gold notes, so that 1 gold dollar might be exchanged for 1.25 greenback dollars, say, depending on confidence in the government.

The system of dual currencies persisted after the war and into the Grant administration. Greenbacks were used in most domestic transactions, but gold dollars were mandated for the payment of taxes and were needed for conducting foreign trade. The naturally limited supply of gold gave the gold notes their value but also tempted speculators to manipulate its price to their benefit.

Jay Gould and Jim Fisk were two such speculators. Like a card-counter at a blackjack table, Gould monitored the action in the Gold Room, a special chamber on Wall Street where gold was bought and sold, and mentally measured the supply available for purchase against his estimates of current and imminent demand. Gould reckoned that under the right circumstances he might purchase enough gold to corner the market — dictate the gold price to those people who needed gold to pay their taxes and foreign debts. Jim Fisk was Gould's front man, as loud as Gould was secretive.

The two men approached Grant. The great imponderable in their scheme was the response of the government. The vaults of the U.S. treasury contained sufficient gold to break any attempted corner should the president order the vault doors opened. Gould and Fisk sought to persuade Grant not to intervene in the operations of the market but rather to let gold find its own level.

Grant appeared amenable. He was no economist, yet he lived in an age when government intervention in the workings of markets was almost unheard of. He evinced no inclination to become a pioneer in the fields of monetary policy or financial regulation.

Gould was heartened but not convinced. He knew that as his grip on the gold market tightened, those caught in the squeeze would run to the government for relief. Grant would come under pressure to sell the government's gold and break the corner.

Gould hedged his bet. He made covert partners of a treasury official and Grant’s brother-in-law. These men were given stakes in the operation and thereby an incentive to assist in its success. At the least they would warn Gould of a change in Grant’s policy.

Gould cloaked his intentions by enlisting dummy buyers who didn't know who they were buying gold for or for what purpose. To the outside world the consequent rise in the gold price seemed nothing more than a sign of market optimism. Jim Fisk, known for his good cheer, made his presence exuberantly felt in the Gold Room.

Up and up went the price. At any given time speculators in gold were divided into two camps: the bulls and the bears. The bulls were betting on higher prices, the bears on lower. The bulls bellowed in triumph as the price rose. The bears roared in pain.

Fisk led the bellowing, shouting that gold would go up still more. Gould stayed in his office, calculating what remained to achieve the corner. A few more purchases and the deed would be done. The gold debtors caught short would be at his mercy, having to cover their debts at whatever price he demanded.

Then, suddenly, he heard what he had dreaded. Grant’s brother-in-law sent a telegram indecipherable to anyone else but indicating that Grant had changed his mind. This could mean only one thing: the government was going to enter the market and sell its gold.

Gould told no one, not even Fisk. Gould's covert brokers knew only that they were to stop buying and start selling, quietly but swiftly.

He and they got a jump on the tsunami that hit the Gold Room when the treasury announced its gold sale. The bears, who had seen their lives passing before their eyes only hours earlier, swooned in relief. The bulls bellowed louder than ever but this time in agony and anger.

All parties awoke to the fact that Gould and Fisk, master manipulators, were behind the whole operation. Fisk ran for his life to the office he shared with Gould, where they barricaded themselves behind stout doors and a cordon of street toughs.

Sorting through the wreckage of Black Friday, as the day became known in American financial history (before the label was repurposed with a different meaning), took months. The financial system shuddered but didn't collapse.

Gould kept his own counsel. Fisk observed with characteristic nonchalance, “It was each man drag out his own corpse."

Grant had survived some close battles during the war. This was a battle of a different sort but no less close. During the war he had relied on his assessment of the opposing commanders, finally and crucially Robert E. Lee.

This time he had sized up Gould and Fisk and weighed their counsel against what he judged of their motives and track record. His conclusions overrode his reluctance to break new ground in the relationship between government and business and spared the country its first full financial panic of the industrial era.

Or rather postponed it — to 1873, when speculation in railroads rather than gold was the trigger.

I must say it: You, sir, write impeccably fascinating history. Sincere thanks for these essays.

Great stuff indeed, written with just the right amount of color and detail.