Thinking the unthinkable

My mother was sufficiently younger than my father that they often spoke about what she would do after he died. Would she stay in the house they had shared for forty years or get a new place of her own? Would she continue to do things they liked to do together, or would she take up new activities and hobbies?

They never had the conversations in front of me, but when I heard about them I got a queasy feeling. It seemed disrespectful or maybe just bad luck to talk about my father in the past tense while he was still alive.

In fact it was a good thing they had those conversations. He predeceased her by several years, and the decisions she had to make upon his death didn't take her by surprise. I think she made good decisions. I think he would have thought so too.

But my unease wasn't unique to me. Indeed discomfort at planning for unfortunate events has often shaped public policy, and not in a good way.

Two instances demonstrate the tendency.

During the last eight decades, great effort has gone into thinking about how to avoid a nuclear war. Theories of deterrence have evolved and ramified, employing thousands of the brightest minds in several countries. By comparison, very little effort has gone into planning for what happens if deterrence fails. A nuclear World War III is typically treated as the end of human history, beyond which it is useless to conjecture.

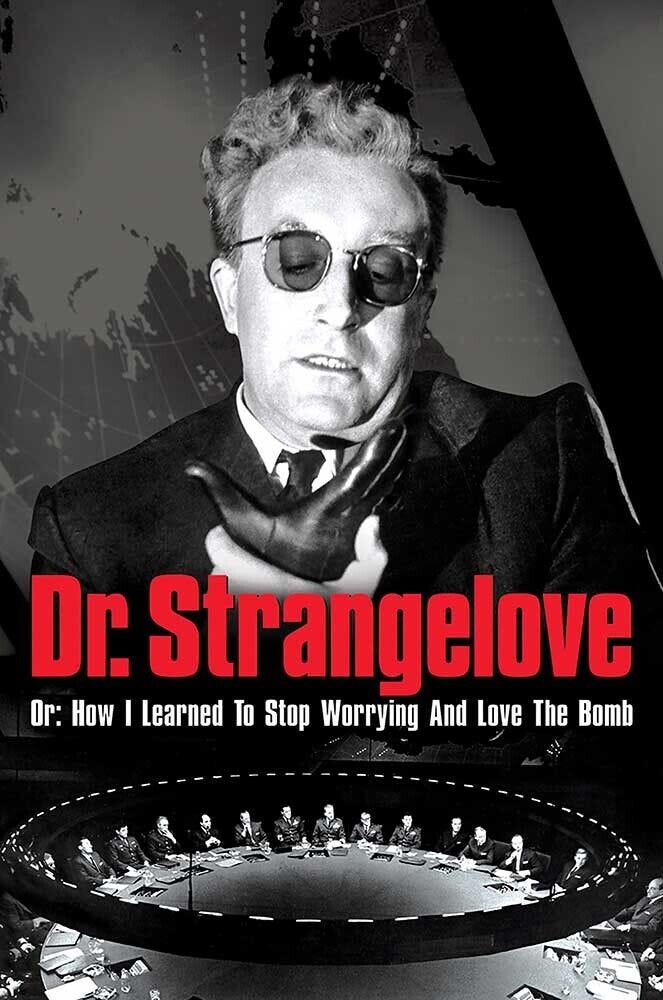

More than that, those mavericks who have conjectured beyond World War III have been treated as tempters of fate with more than a few screws loose. The best example was a nuclear strategist at the Rand Corporation named Herman Kahn, who was satirized as the mad scientist in the black comedy movie Dr. Strangelove. The critique leveled at Kahn was that by treating nuclear war as something that might actually happen, he weakened the nuclear taboo and made nuclear war more likely.

Thankfully, it's impossible to say if he did or didn't. We haven't had a nuclear World War III. But we're not sure why not. Perhaps he brought it closer, but not so close that it actually occurred. Perhaps his theories had no effect one way or the other. Conceivably, by making people think seriously about nuclear war, he actually made it less likely. We just don't know.

The nuclear question hasn't gone away. But another question has become more ubiquitous. Can humans get a grip on the emission of greenhouse gases that have caused temperatures to rise around the world? Or are we all doomed to fry?

Here the question that many people don't want to think about is: What if we fail to restrain rising temperatures? For years the hope of various international bodies has been to keep average temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial norms. The thinking goes that below 1.5, life as we know it might manage to carry on. Above it, all bets are off.

To plan a fallback position, to prepare for failure to halt the rise at 1.5 or below, is often seen as defeatist and demoralizing. Rarely does anyone admit to a political strategy based on the idea that the only way to get action is to scare people out of their wits. But the refusal to look beyond 1.5 suggests that such a strategy is in play. To plan for a 2.0 or 2.5 future suggests that the doomsday scenario is overdrawn. The world will not end at 1.6. And if that's true, how serious can the problem really be?

These attitudes are understandable. But they're more appropriate for children than for adults. We can handle the truth.

This isn't the worst of it. In 2024, it seems unlikely the world will meet the 1.5 standard. The goal posts are already being moved by some to 2.0. Maybe temperatures will stop rising before hitting that new mark. Maybe they won't.

And if they don't, the governments of the world need to make plans for dealing with the consequences. Such plans necessarily have long time horizons. You can't transform infrastructures and move populations overnight.

Today's climate warriors might curse you for defeatism. But tomorrow's survivors, the millions of people whose lives will be saved by advance planning, will thank you.

The world is NOT going to reduce emissions in any meaningful way. China and India (and recently the nuclear-phobic Germans) have all embraced King Coal.

The world WILL run this climate experiment.

Cheap energy makes life easier. While elite westerners drive Tesla's to wind and solar conferences, 3 billion of the world's poor demand coal powered air conditioning and inexpensive gas/diesel vehicles.

The solution, if the enviro left was serious and numerate, was nuclear power to relplace coal and natural gas as a cleaner replacement for combustion uses.

I am skeptical we will address climate in any meaningful way. This is a global issue which needs governments' to address at a societal level.

For the USA, unfortunately, we have an absurd mix of philosophies which will continue to undermine a concerted society level effort.

1. outright climate change deniers have too much influence

2. too many with vested (read financial) interest in maintaining fossil fuels have too much influence

3. the wealthy who always seem to avoid consequences of such issues because they can afford the individual means to alleviate the imact on their lives

4. the American "individual should work to make an impact" attitude -i.e. that it is up to individuals to do their part only if THEY want to

5. the "how do we pay for it" crowd which really means "we don't want to do it"

6. Finally,the gradual nature of climate change and climate chaos- unlike nuclear war, which is almost instantaneous, climate is such a long term change that the impact is the proverbial "frog in a pot of water" effect