Thinking and language

Is thinking possible without language?

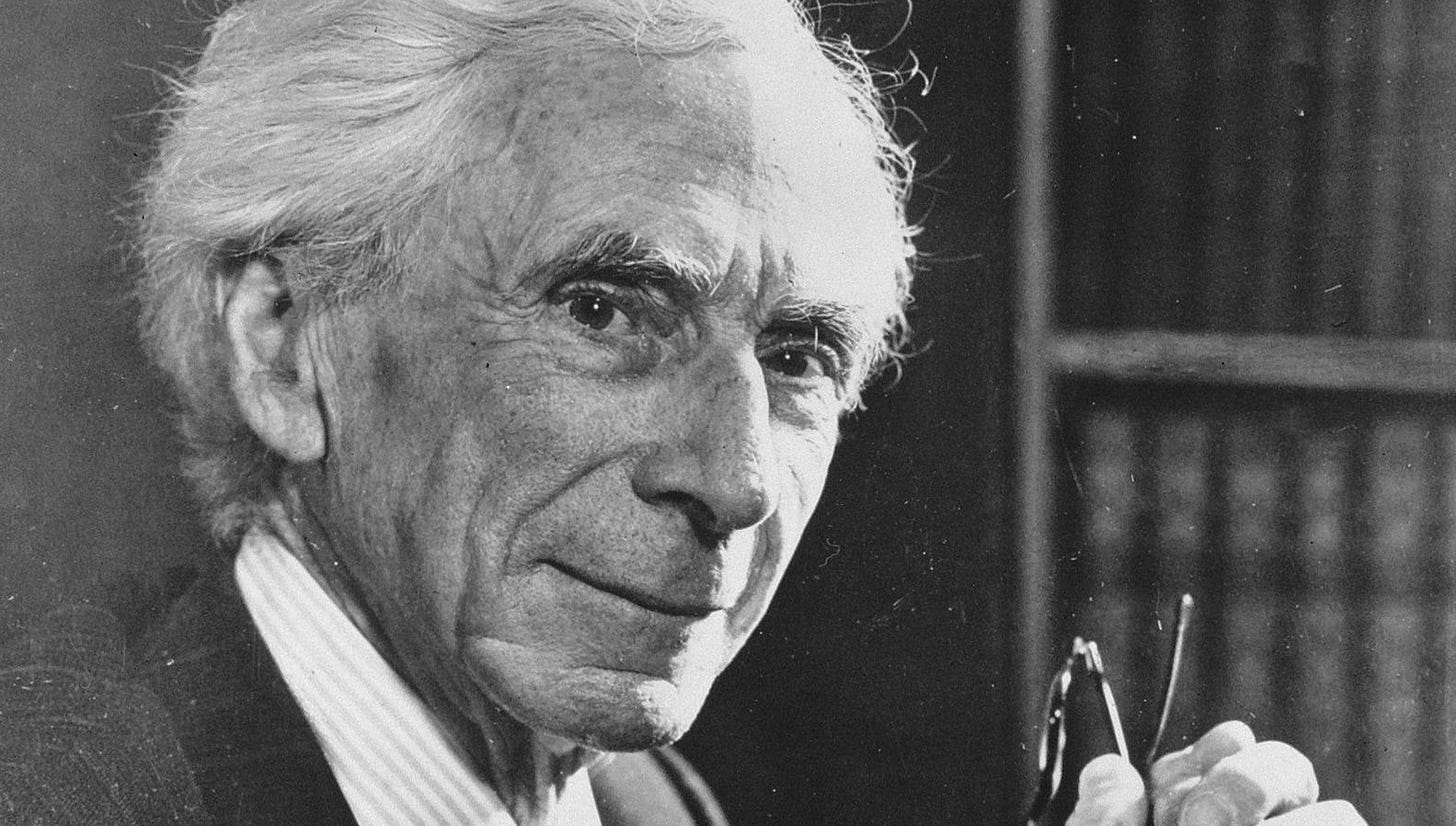

Bertrand Russell said yes, within limits. ”Language serves not only to express thoughts, but to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it,” the British philosopher declared. “It is sometimes maintained that there can be no thought without language, but to this view I cannot assent: I hold that there can be thought, and even true and false belief, without language. But however that may be, it cannot be denied that all fairly elaborate thoughts require words.”

Russell gave an example from mathematics. “I can know, in a sense, that I have five fingers, without knowing the word ‘five,’ but I cannot know that the population of London is about eight millions unless I have acquired the language of arithmetic, nor can I have any thought at all closely corresponding to what is asserted in the sentence: ‘The ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter is approximately 3.14159.’”

This seems reasonable enough. Except that his circle example begs the question—in the old Aristotelian sense of assuming the conclusion. Geometers realized that the ratio of circumference to diameter was the same for all circles long before anyone calculated the decimal value of that ratio. In fact the decimal representation is inferior to the geometric one in that it is always only approximate.

This is like asking whether a person can think of blue without having a word for blue. And the answer here is similarly equivocal. Many languages have multiple words for blue, signifying different shades. Speakers of those languages have an easier time thinking of variants of blue than speakers of languages with a single word for the color.

Which begs another question—in today’s colloquial sense of presenting for consideration. Do people who are facile in language think more effectively than people whose language skills are restricted? Bertrand Russell was an excellent writer. He was also an excellent thinker. Was there a connection?

Quite probably, if only because philosophy, the kind of thinking Russell specialized in, is rooted in language. Philosophy isn't just thinking, it’s thinking about thinking, and talking about that. Philosophy is a kind of word game, so naturally people good with words have an edge.

In other specialized fields, the connection between thinking and language appears less important. Chess masters tend to think visually, imagining the board one or two or more moves ahead. Divers, gymnasts and snowboarders planning new moves think spatially and kinetically.

What got me thinking about this right now is the approach of the autumn semester. I’m wrestling with how much writing to require of my students, and how artificial intelligence is changing the writing enterprise. Ten years ago I was fairly confident of a close correlation between a student’s ability to think about history and that student’s ability to produce an essay on a historical question or topic. Well-crafted essays betokened clear thinking.

I’ve lost a lot of that confidence. Students, with the help of AI, can produce pretty good essays without acquiring a comparable deftness in historical thinking. Sometimes I can spot the AI contribution, but not always.

I have to ask myself: What’s the learning objective here? In an ideal world—you know, the world that existed when we were young—my students would become both insightful thinkers and persuasive writers. But the real world of large classes in public universities requires making tradeoffs. I also have to allow for the fact that for many of my students, English is their second or third language.

There’s something else. I want my students not simply to think about history analytically but to imagine it emotionally. Empathy is an indispensable item in the historian’s toolkit. In fall semesters I have students read about Josie Mansfield, a Gilded Age femme fatale—literally: one of her lovers murdered another. I ask students to imagine what Josie was thinking in all this but also what she was feeling.

The students convey their conclusions in an essay. This is the part of the assignment on which they are graded, and consequently they think it’s the most important part.

But it’s not the part most important to me. If there were other ways for students to demonstrate that they had put themselves in Josie’s place and done so seriously, I’d be happy to use those as metrics. If I had fifteen students instead of five hundred, I’d have a chat with each one individually.

The semester doesn’t begin until late August. I’ve got time to decide.

The scholarship on the relationship of thinking and language is extensive. This human capacity to know symbolically as apposed to what is often called active or enactive knowing, as when one learns to ride a bike. Or a level of iconic knowing that draws upon images, pictorial representations, etc. all so important in the growth of knowledge. But it is the realm of symbolic knowing that opens a much vaster range of possibilities for humans to create, to think more imaginatively and to go way beyond the here and now. And because of language Prof. Brands tries to employ it to improve the historical thinking of his students. He deserves so much credit in giving the time in thinking about the ways he can help his students through their writing to achieve this level of understanding.

There aren't many college instructors that work on their teaching as often as not they are into their own research or so often this is not given near the consideration when it comes to peer reviews. Fortunately of late this seems to be changing.

From my own experience teaching well requires an effort to improve in the manner of delivering the course material or thinking of the ways to engage with the students so they can think better about the subjects at hand.

I always valued the role student writing can assist them to these higher and more critical levels about the subjects under discussion. There was a time when we did a lot of reading of one another's writing and thereby engaged in some fine ideas but also manners of expression. This worked well with some. Not others.

There is always the concern that students will draw upon their own words and forms of expression rather than taking them from other sources and no doubt AI opens opportunities that must be handled carefully. If used well this can become a welcomed addition for students to grow in their thinking. It is a world I have never worked in. I do know when we were about to write I tried to keep the topics within the range of texts and the articles we all used. This way I had a pretty good sense and whether it was the students writing or that taken from other's work.

There will always be ways to improve on teaching the young. I appreciate the topics you experiment with and look forward to how all this goes in the new school year.

If I were writing that essay I might write it as a letter from Josie to a friend or sister. In that way I would be hoping to outwit AI’s ability to express intimacy if it is at all capable of doing that. Do you think an essay in that form would be an improvement?