“Where do you reside, Mr. Morgan?”

“New York.”

“Are you the senior member of the partnership or firm of J. P. Morgan & Co., bankers, of New York City.”

“I am.”

“Are you also a partner in other banking houses in this country and elsewhere?”

“No, I am not.”

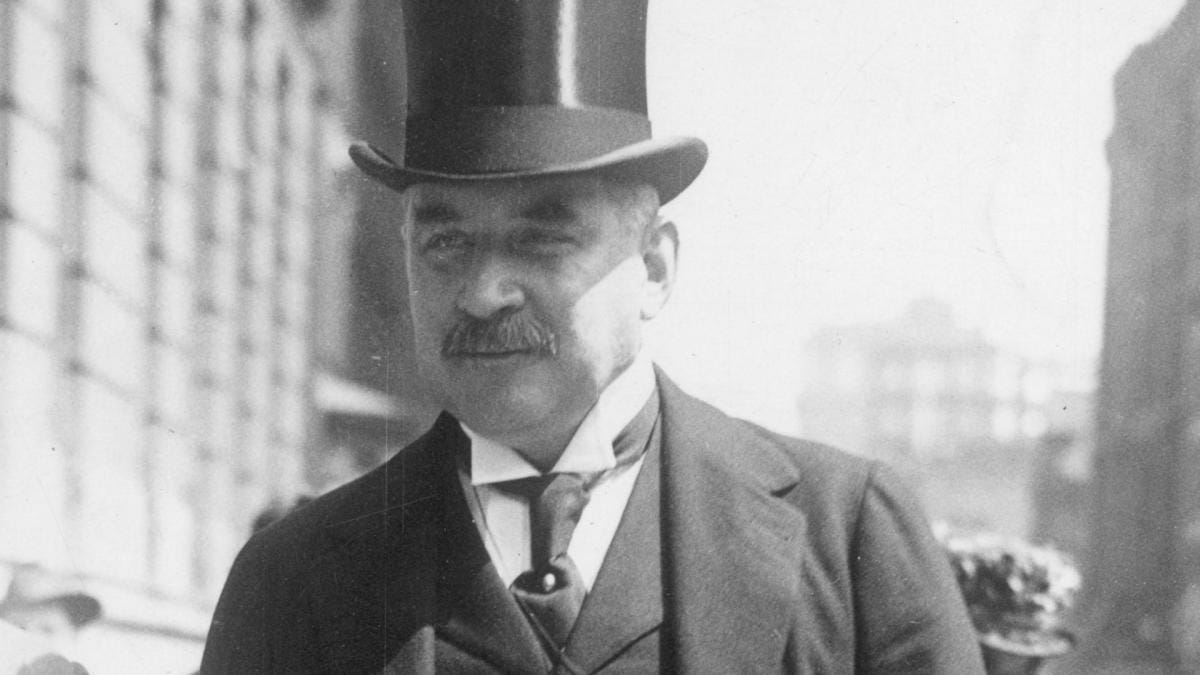

The eyebrows of Samuel Untermyer lifted at this response. John Pierpont Morgan, called Pierpont by his associates and Jupiter by his critics, was the most prominent banker in America, with interests that spanned the country and extended to Europe and other continents. He had been summoned to Congress to testify before the House Committee on Banking and Currency, chaired by Arsène Pujo of Louisiana. The committee’s aim was to reveal the workings of the interlocking directorate of finance that dominated credit markets in the United States. At the middle of the network, like a spider at the center of a web, sat J. P. Morgan.

Samuel Untermyer, chief counsel for the Pujo committee, hadn’t expected Morgan to be a cooperative witness. Morgan’s other nickname was Sphinx, for his taciturnity about his business dealings. Yet Untermyer had supposed he would get beyond his third question before Morgan balked.

“Are you not interested in the Philadelphia firm?” asked Untermyer. Morgan had partnered decades earlier with Anthony Drexel of Philadelphia; Drexel, Morgan & Co. had become J. P. Morgan & Co. upon Drexel’s death. The firm still had offices in Philadelphia.

“That is the same thing,” Morgan explained. There was no separate Philadelphia firm.

“That is the same firm with the same membership?”

“Yes.”

“Is that true also of the London and Paris houses?” Morgan & Co. had offices in those European capitals.

“The firm in New York are partners in the Paris house and in the London house.”

Untermyer breathed easier. Morgan was admitting that the reach of his company was more direct than generally thought. Untermyer pressed on: “Will you name the partners in the New York and Philadelphia houses?”

The chief reason Morgan didn’t testify to Congress was that he deemed its members fools or knaves, and he didn’t suffer either gladly. His impatience began to surface. “I don’t know,” he said dismissively, in response to the request to name the partners. “I think you have them.”

Morgan’s attorney, sitting beside him, suggested that Untermyer read off the names he had, and Mr. Morgan would confirm if they were partners.

Morgan prided himself on his mastery of detail; his steel-trap mind was his main asset in designing and effecting the mergers and acquisitions that made him the master of finance. Notwithstanding his disclaimer, he knew who the partners were. “I can call them off,” he said.

Untermyer read them anyway, eleven in all. He proceeded to ask Morgan about the assets of his bank. “Can you give the committee the total deposits you had on November 1?” That was November 1, 1913, six weeks prior to the current session.

“I haven’t it here,” Morgan said reflexively. He didn’t like anyone, including members of Congress, knowing the details of his business. But he concluded that Untermyer would find out anyway. “About $100 million,” Morgan said.

Untermyer asked about Morgan’s influence with the companies to which his bank had made loans. The United States Steel Corporation was the pièce de résistance of Morgan’s merger work, fabricated in 1901 from ten leading steel firms; upon completion of the merger it became the first billion-dollar corporation in history. “At the time of the organization of the Steel Corporation, did you name the entire board of directors?” asked Untermyer.

“No, I think I passed on it,” Morgan said.

Untermyer frowned. “Did you not, as a matter of fact, name the board, passing out a slip containing the names of the directors?” he demanded.

Morgan obliquely acknowledged as much. “I cannot say that no one else helped me in it,” he granted. “I am willing to assume the final responsibility, if that will answer your question.”

Untermyer moved to the present. “The board is named by you and your associates?” he asked.

“Not now.”

Untermyer rephrased. “Nobody is nominated for that board without your approval, is he?”

“Yes.”

Untermyer rephrased his question again, to remove any ambiguity from Morgan’s answer. “Is anybody nominated for it against your protest?”

“Not against my protest.”

Untermyer asked about Morgan’s holdings of shares of other banks. “You have a very large interest in the National Bank of Commerce, have you not?”

“I do not remember,” Morgan said. “Not very large, about a million dollars.”

A laugh rippled around the committee room. The laughter suggested that only a very wealthy man would not consider a million dollars a large sum of money.

Untermyer milked the moment. “You have a large interest in the National Bank of Commerce, have you not?”

“Not very large,” Morgan repeated. “About a million dollars.” He looked at a paper in Untermyer’s hand and said, in a tone of annoyance, “You have the statement there.”

“You have $1,686,000,” Untermyer said.

The lawyer continued to probe, the banker to resist. Morgan denied having the kind of power commonly attributed to him. “I have been in a good many banks and corporations and I defy any man to go into any of those boards—even myself, I will say that for the sake of argument—I do not believe I could carry any one question through any one board in which I was a director, against the views of the other directors. I have a great quantity of cases where I could bring in proofs of this. There is no question of control unless you have got a majority of the directors in all the banks.”

Untermyer asserted that Morgan sought to control the credit available to businesses in the United States. Morgan wanted to create a money trust, if he hadn’t done so already.

Morgan denied it. “I want to control nothing,” he said. Anyway, credit defied control.

Untermyer affected not to understand. “What is the point, Mr. Morgan, that you want to make?”

“That there is nothing in the world by which you can make a money trust.”

“There is no way one man can get it all?”

“Or any of it, or control of it.”

Morgan must be exaggerating, Untermyer said. Surely a man could control some portion of the money—some large portion. From there he might try to control the rest. Could he not succeed?

“He cannot,” Morgan insisted. “He may have all the money in Christendom, but he cannot do it.”

“How about credit?” asked Untermyer.

“Credit also.”

Untermyer didn’t believe it. Certainly Mr. Morgan would admit that his control of banks gave him control of credit.

Morgan denied this too. He said Untermyer misunderstood the dynamics of credit, which depended more on character than on collateral. “I have known men to come into my office, and I have given them a check for $1,000,000 when I knew they had not a cent in the world,” Morgan said.

Untermyer cocked an eyebrow. “There are not many of them?” he said skeptically.

“Yes, a good many.”

Untermyer was unconvinced. “Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?” he said.

“No, sir. The first thing is character.”

“Before money or property?”

“Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it.”

Untermyer continued dubious. Morgan’s bank must check the credit ratings of its customers, to see if they had bonds or other collateral, he said.

Only after the customer passed the character test, Morgan said. “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.”

The inquisition lasted hours; at the end, Morgan’s banking associates thought he had held his own. “A committee of Congress, chasing what some folks say is a chimera, has elicited from perhaps the most renowned witness in the country's history the most vital testimony,” one remarked. “Their brilliant counsel, who could say with Aeneas that he once had been part whereof he spoke”—Untermyer had worked in finance— “was molding the case as a sculptor plays tricks with clay.” The drama played out. “The uncrowned king of finance was compelled to justify his reign.”

And he had done so magnificently. “For three long hours he, now past the scriptural age limit, faced the inquisitor,” the Morgan associate continued. “Seldom has a courtroom produced so acute, searching and profound a cross examination. Rarely has a witness emerged so triumphantly. Where two continents had expected a sullen silence or passionate resentment, there ensued three hours of suave, good-natured thrust and parry. Jove condescended; the Sphinx turned talkative.” Morgan had made a powerful case for the financial industry as a positive force in American life. “He appraised and explained Wall Street. He did not have to defend it; he justified it.”

Morgan himself didn’t share the triumphal feeling. Another reason he avoided speaking in public was that he found it trying. His words moved markets, and he had to choose them carefully. He emerged from this examination tired and worn. He embarked on his annual holiday to Europe and the Mediterranean, where he expected to acquire new pieces to complement his exquisite art collection. He cruised up the Nile, as he had on previous occasions. The temples, the desert, the timeless sky revived him. He circled back to Rome.

In the Eternal City he fell suddenly and mysteriously ill. In a matter of days he was dead. The Italian doctors had no explanation, but his personal physician blamed the grilling Sam Untermyer had subjected him to. The members of the Pujo committee denied that their treatment of Morgan had been anything but respectful.

Yet their denials didn’t prevent Congress from passing a law that seized for government the power over American finance Morgan had long possessed. The Federal Reserve Act would have diminished Morgan had he lived; in the event, it precluded the emergence of any new Morgan.

Morgan’s passing marked an epoch in the history of American capitalism. For half a century titans like Morgan, John Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie had constructed edifices of enterprise that intimidated the institutions of democracy. Congress, the courts and the press did their bidding. But the titans overplayed their hand, and in the last years of Morgan’s life the most ardent defenders of democracy—the progressives—mounted a counterattack. Whether or not Morgan the man was a casualty of the counterattack, Morgan the institution was. The Morgan bank survived, but democracy’s central bank—the Fed—now called the tune the economy danced to.

Just great stuff. I hear echoes of today and other periods in US history where things got severely out of balance. In the late 19th century wealth represents certain forces which were severely out of balance (Morgan's overall demeanor and appearance in Congress sums this up very well) and it served to strengthen the progressive movement and men like T. Roosevelt. Bill Rusen

I am most fascinated by the text "the most ardent defenders of democracy -- the progressives" in light of the current environment in the US, where "progressives" seem to be pitted against "populists", both of which seem to now be terms of opprobrium.

I don't know how the changes in culture have modified the meaning of those two terms, much in the way that "left" originally referred to, IIRC, the revolutionaries in 1789 and the "right" referred to the royalists (and even now have completely different meanings in reference to the politics in Europe and the US, leaving out the rest of the world).

There is also some irony here in that Morgan was, presumably, attacked because he held too much power. But now, who has this power? the chairman of the Federal Reserve. Is that better? Is he/she/it less corruptible than JP Morgan? Does he/she/it "[intimidate] the institutions of democracy"?

And I can't let this go w/o a comment that the US is NOT a democracy. We are a federal republic with more-or-less democratically elected representatives.