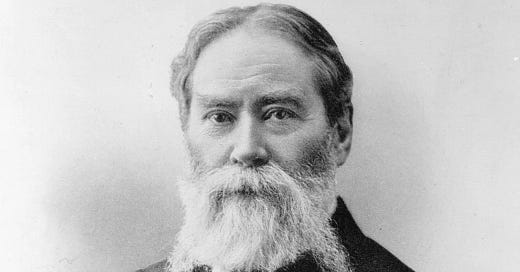

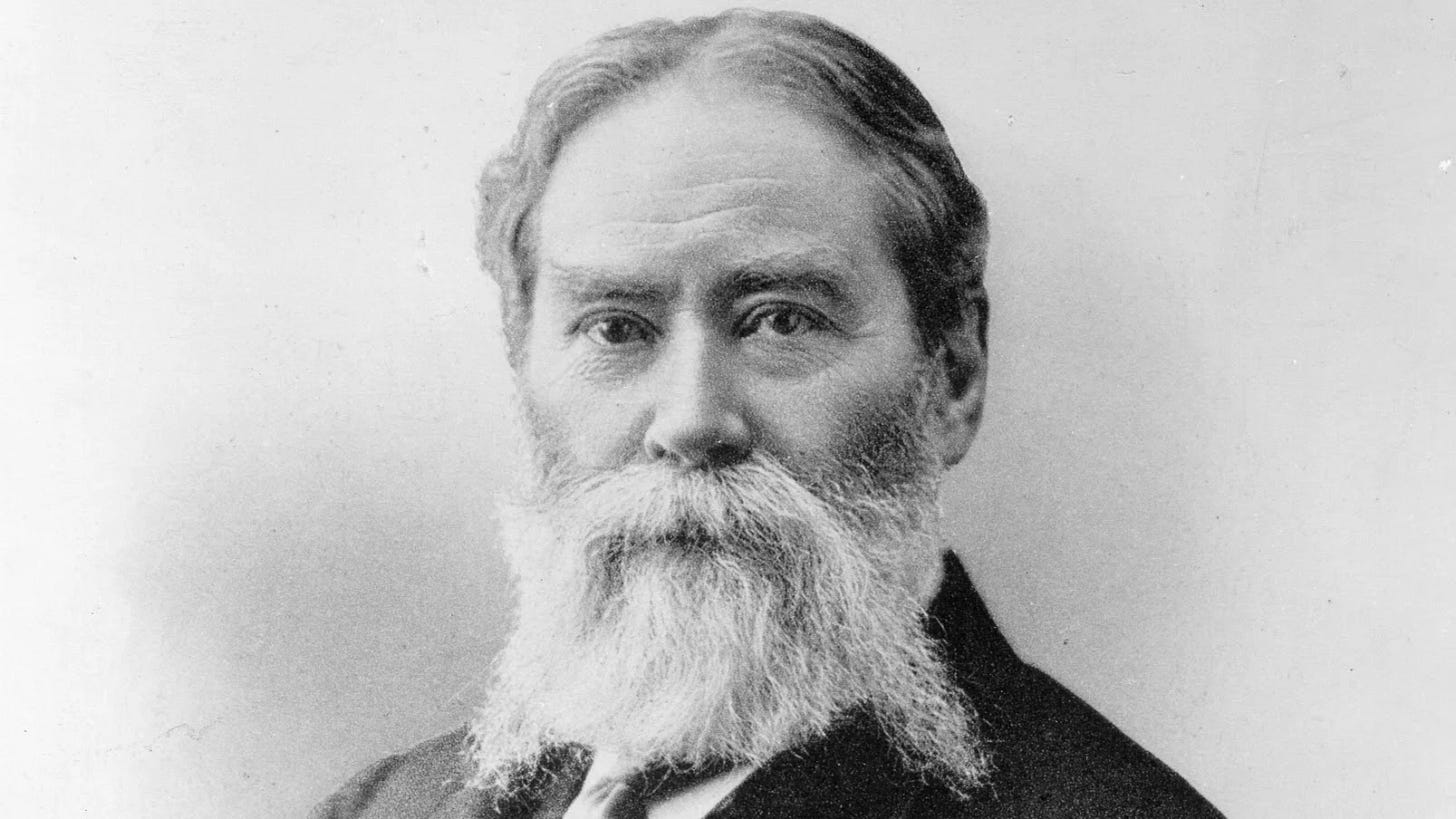

“After our Constitution got fairly into working order, it really seemed as if we had invented a machine that would go of itself,” James Russell Lowell wrote in 1888.

The framers of the Constitution weren't all deists. But all were influenced by that Enlightenment version of divinity, in which God was seen as the ultimate watchmaker, who crafted the universe so cleverly that once set in motion, it would operate on its own without further intervention. They hoped for something similar with their Constitution. The people were the spring, the motive force. The three branches of government were the gears. The checks and balances built into the Constitution were the ratchets and cogs that would keep the mechanism in order and under control.

Things hadn't worked out as planned, as Lowell, writing after the Civil War, was painfully aware. But by the late 1880s the damage done by that conflict had been repaired, and it was possible to revive the original hope. “Circumstances continued favorable, and our prosperity went on increasing,” Lowell wrote. The hope, though bruised by experience, spoke well of America. “I admire the splendid complacency of my countrymen, and find something exhilarating and inspiring in it.”

The founders’ hope is with us still, and it accounts for the faith Americans place in our republican government. If our Constitution goes of its own, it doesn't depend on the genius of each generation to keep it operating. The framers might have been demigods, as Jefferson called them, but subsequent users can be mortals. The machine will guide their ambitions and energies into the channels the framers intended.

The problem is that the model is misleading, in two senses. First, it inaccurately portrayed the past. The machine never did go by itself. It required regular tinkering. The 12th Amendment rejiggered the unworkable original version of electoral voting for president. The Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 kept slavery from blowing up the Union. And of course the Union did blow up during the Civil War. Six hundred thousand deaths and three constitutional amendments were required to piece it back together.

The model was misleading in a second, forward-looking sense. It tended to absolve citizens of their responsibility for keeping the machine in order. Lowell was dismayed by the corruption of Gilded Age democracy. He blamed Americans’ faith in the constitutional machine for their not maintaining the mechanism. “It is certainly a great privilege to have a direct share in the government of one's country, but it is a privilege which is of advantage to the commonwealth only in proportion as it is intelligently exercised.”

The large population of America by the late 19th century contributed to the neglect. Democracy had emerged in America in New England town meetings, where voters could directly observe the impact of their decisions. “But in a democracy as vast as ours, though the responsibility be as great (I remember an election in which the governor of the state was chosen by a majority of one vote), yet the infinitesimal division of power well nullifies the sense of it, and the responsibility implied in it.”

The second election of Donald Trump was, among other things, a rejection of the idea that our constitutional machine would go of it itself. Many Trump voters believe that the federal government has grown beyond control. Trump’s backers support his post-inaugural assault on various agencies and departments of the government. The constitutional institutions that created this mess are unable to deal with it, they say. The extra-constitutional forces Trump has brought to bear — notably the so-called department of government efficiency headed by Elon Musk — have become necessary to save America.

Trump's strategy might or might not succeed. What the president and his aides have in mind beyond breaking the existing model of government is unclear. A new model? A new constitution? Or will a thorough reboot allow the old machine to resume operation satisfactorily?

He and they aren't saying. Quite possibly they don't know. Sometimes you don't realize how bad the damage to a machine is until you take it apart.

Once apart, though, it can be difficult or impossible to put back together. At which point Americans might decide it wasn't working so badly after all.

The grass isn’t always greener