“The hotels were thronged,” wrote the reporter. “The streets were filled with restless, impatient people. The headquarters were surrounded by crowds of anxious men, who desired above all things to witness the execution, and who were willing to spend hundreds of dollars for that poor privilege. All day long the trains came in loaded with people from the North; all night long the country roads were lined with pedestrians, with parties hurrying on to the city, where they might at least participate in the excitements of the occasion. Officials of every grade and name, with or without influence, were pestered by applications for tickets; the subordinate officers of the department were approached in every conceivable way, and by every possible avenue, by those whose idle or morbid curiosity impelled them to come to this hot and sweltering city in search of food for gossip and remembrance.”

The event was the hanging of the four persons convicted of conspiracy in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The assassin himself, John Wilkes Booth, had evaded public vengeance by refusing to surrender to the authorities who had run him to ground; he died in the shootout. The outraged populace had to settle for the execution of those who had aided Booth.

Few questioned the guilt of the three men on the scaffold this day. But the woman, Mary Surratt, to many appeared less culpable. She owned the house where the plotting against the president took place; the prosecution contended that therefore she must have known what the plotters intended and, by doing nothing, approved.

The prosecution’s case rested on the testimony of two men whom the defense branded as unreliable, one from a fondness for liquor, the other from self-interest. The case was weakened further when one of the other defendants avowed Mary Surratt’s innocence.

Yet the military court trying the case voted to convict, with several of the nine judges apparently thinking she would be spared the death penalty on account of her sex. The United States government had never before executed a woman. Indeed, five of the nine judges wrote a letter to Andrew Johnson, urging the president to commute her death sentence to life in prison.

Johnson was of no such mind. The Tennessee Democrat, who had been added to Lincoln’s ticket in 1864 as a gesture of national unity, was already suspect among Northerners and Republicans for being of the wrong section and the wrong party. Clemency toward one associated with the murder that had made him president would have made Johnson more suspect still. He signed Surratt’s execution order. “She kept the nest that hatched the egg,” he was said to have declared.

Mary Surratt gave no sign of distress. “Those who have watched her through the whole of this protracted trial have noticed her utter indifference to anything and everything said or suggested about her,” the reporter remarked. “The most terrible flagellation produced no effect upon her rocky countenance. Stolid, quiet, entirely self-possessed, calm as a May morning she sat, uninterested from the opening to the close.” When the sentence of death was announced, she stated simply, “I had no hand in the murder of the President.”

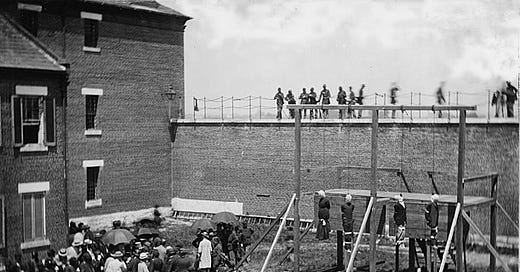

The wheels of justice in those days turned swiftly. The second day after the signing of the death warrant was the day of the execution. “In the lot south of the prison, and surrounded by a wall thirty feet high, the scaffold was erected,” the reporter said. “The structure is about seventy feet from the prison near by, say thirty feet distant, were four freshly dug graves, and beside them four large pine coffins coarsely constructed. The scaffold was so arranged that the four condemned could be hung at the same time.”

Mary Surratt was the first to mount the scaffold. “Her waist and ankles were ironed; she was attired in a plain block alpaca dress, with black bonnet and thin veil. Her face could be easily seen. She gazed up at the horrid instrument of death, and her lips were moving rapidly as in prayer. She was assisted upon the scaffold and seated in a chair near the drop. She gazed upon the noose, which dangled in the wind before her face, and again her lips moved as if in prayer.”

The three male prisoners had preachers to pray for them. Mary Surratt declined a similar offer from a Catholic priest assigned to her.

The officer in charge read the death warrants. The arms and legs of each prisoner were bound. Hoods were drawn over their heads.

Mary Surratt started to lose her balance. “Don’t let me fall; hold on!” she said to the guard beside her.

Suddenly the officer in charge gave the order. The floor fell away beneath the prisoners. The ropes snapped taut.

“Mrs. Surratt appeared to suffer very little,” the reporter wrote.

A good reminder why justice is often depicted as blind and rightly so.