The last few decades have been hard on public education in the United States. The Reagan years saw a shift in attitudes regarding government, from the confidence of the half century from the New Deal through the Great Society, to the skepticism of the post-Vietnam, post-Watergate generation. Reagan codified the skepticism by declaring government to be not the solution to America’s problems but the problem itself. Since Reagan, many Republicans have gone farther to the right, declaring government to be not simply the problem but the enemy.

This has been bad news for public schools, which emerged in the early nineteenth century on the premise that public education was a public good: that the community as a whole—and not simply the students and their families—benefited from an educated citizenry and a productive workforce. The Reagan model of conservatism challenged this view, emphasizing individual self-interest rather than communitarian sentiment, in education as elsewhere. The Reagan conservatives also opposed the teachers’ unions that had grown strong in many public-school systems. These two factors fueled Republican efforts to redirect funding from public schools to charter schools and other alternatives, and they often succeeded.

They received help from many people who considered themselves liberals on other subjects. On the whole, liberals endorse the idea of public schools as promoting democracy and mitigating inequality. But when liberals become parents, their practical concern for their own children frequently outweighs their attachment to democratic theory. They might still vote for school bond issues even as they send their kids to charter schools or private schools. Conservatives often assail these decisions as hypocritical, but they’re the sort of thing most parents consider perfectly natural. The community is important, but our kids come first.

The combative partisanship of the 1990s and after added to the woes of the public schools. Since at least the Scopes evolution trial of the 1920s, school boards and their constituents have battled over what should be taught in the schools. It’s appropriate that they do so; if the public is paying for the schools, the public ought to have some say in what the schools teach. Moreover, students in public schools are a captive audience; by law they have to be there.

Or they have to be in some acceptable equivalent. Again, parents who sought the best for their kids often responded to the school wars by pulling their kids out of public schools and sending them elsewhere. The wars over the curriculum were rarely about the curriculum per se; they were opportunities for politicians to posture. But they didn’t serve students well, and parents got the message.

Then came covid. Nearly all schools went online for a while, but the public schools were the slowest to resume face-to-face instruction. Sometimes the caution reflected an unwillingness to use the power of government to order students into potentially compromising situations, which might thereby compromise the health of people the students lived with. Sometimes the teachers’ unions refused to put their members in potential jeopardy.

Private schools had more leeway. In many cases the parents of their students were more personally invested in their kids’ education, and, recognizing that Zoomed classes simply aren’t the same as the real thing, they insisted on the real deal. And, once again because no one is compelled to attend a private school, administrators of private schools felt freer to prioritize education over a zero-infection standard of health.

Earlier this week the Department of Education released the results of the latest survey of the nation’s public schools; the report card could hardly have been worse. Students showed dramatic declines in reading and math skills since the start of the pandemic. No one with a child subjected to months and months of Zoom classes was surprised, but the published result was still shocking.

And after everything that had gone before, supporters of public schools couldn’t help being disheartened. Bad news in the field of public education tends to produce more bad news. Parents deciding where to send their kids to school would read the new report and start looking more seriously at alternatives. In those places with charter schools, where money follows the students, each student withdrawn from or never sent to public school reduces the public-school funding. Over time, as fewer kids attend public schools, public support for the schools diminishes. As public support diminishes, the quality of the education the schools provide degrades. They become still less attractive to students and their parents, and the downward spiral continues.

Nor is this even the end of the bad news. High home prices in some cities drive families to the suburbs, reducing the potential student base for those cities’ public schools. Mass shootings in schools, and the refusal or inability of government to deal with the issue, causes teachers to reconsider their career choice, producing teacher shortages in many school districts.

The bad news is not just for the schools. Conservatives may not believe public education is a public good, but they and the rest of us will discover that the demise of public education is a public bad. Schools will become segregated again, this time on class lines, with results equally pernicious for American democracy.

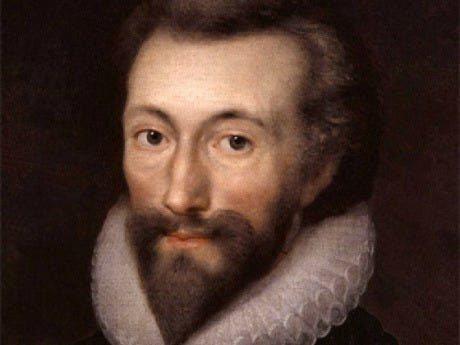

John Donne and Ernest Hemingway knew for whom the bell tolls. Donne was never on the reading list in most American schools, and Hemingway has fallen off, so perhaps a hint is in order: It tolls for us.

I am a public high school teacher and a conservative, so I see both sides. I worked in the private sector for almost 20 years before becoming a teacher. I taught 10 years in private schools, but came to public school for the higher salary and benefits. I could write a book on the problems with education, but I'll say this -- politicians (of both parties) and unions have no incentive to fix the problems in public schools. They all want to be perceived as "doing something" and have thrown untold millions into schools (except for teacher salaries) and there has been no improvement. In fact, by any measure, American education has declined for at least the last 25 years. If a business failed this long, it could not survive, but without any real competition, schools themselves have no real incentive to get better. Most teachers I know work their butts off to do right by their students, but we are hampered by mandates from federal, state and district people who haven't seen the inside of the classroom in years, and have no idea how learning really works. They want to throw money at educational experts and testing companies instead of trusting the people who do the job every day. Nobody speaks for teachers, especially not the unions. It is infuriating that good teachers can't be paid more for being better, but we are trapped in a one-pay-fits-all system that serves no one. I stay because I love what I do, and do my best within the frameworks put on me. I don't want to see public education fail, but at this point, I think it may have to if we ever want to create something better.

As a student, I can say that this is completely and honestly true.