That's easy for YOU to say

But is it therefore wrong?

It's a commonplace that conservatives—in the traditional sense of persons skeptical of change—typically do well by the status quo. Defenders of capitalism, for example, are more likely to be residents of penthouses than people who live under bridges. As a result, conservatism often sounds self-serving.

Should it be discounted for this reason?

Not necessarily. Self-serving arguments should always be scrutinized carefully, but so should other arguments. In law there is the concept of statement against interest, in which testimony prejudicial to the testifier is granted greater weight than self-serving testimony. In real life, determining where self-interest lies is sometimes difficult. When Warren Buffett says taxes on billionaires ought to be raised, this certainly sounds like an argument against interest. But interest can be a broad concept. Buffett values his reputation as an ordinary fellow, despite his great wealth. That reputation might well mean more to him than the money he’d lose if taxes went up.

During the Gilded Age, most scions of the upper class defended their class against efforts to spread the wealth, whether by labor organization, government regulation or higher taxation. But others from easy circumstances took the side of the less advantaged. Theodore Roosevelt led the forces of progressivism during the first decade of the twentieth century; his fifth cousin Franklin Roosevelt picked up the banner of reform during the 1930s. Both men worked against their pecuniary interests but not against their political interests; both men placed higher value on success in the public square than on success in the marketplace.

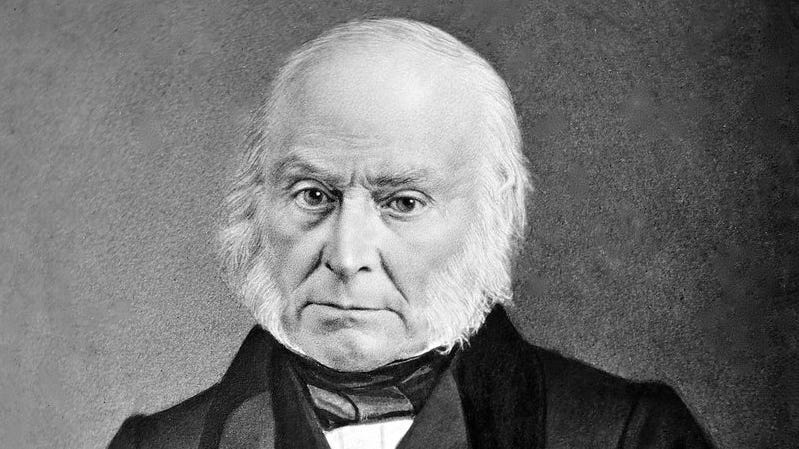

So if arguments against interest shouldn’t necessarily be given extra weight, maybe arguments in favor of interest shouldn’t necessarily be discounted. The presidential election of 1824 yielded a plurality of electors, but not a majority, for Andrew Jackson. The absence of a majority threw the race into the House of Representatives, where the speaker of the House, Henry Clay, helped deliver the victory to John Quincy Adams. Adams proceeded to name Clay secretary of state, a post that in those days often served as steppingstone to the presidency. The Jacksonians cried “corrupt bargain,” linking Clay and Adams in a nefarious quid pro quo.

Both men rejected the allegation. Clay judged that Adams would be a better president than Jackson, and he believed he would be remiss in his public responsibilities if he didn’t act on this judgment. Adams, for his part, thought Clay was the best qualified for secretary of state of those who might win confirmation by the Senate. Both men did what they thought was right, even though they knew they would be criticized for promoting their own interests in doing so.

I don’t consider myself in the same league as Clay and Adams. But as I get older I find myself growing, if not more conservative exactly, more dubious of attempts to change the world in dramatic fashion. My reading of history inclines me to believe that lasting change arrives incrementally, and that efforts to accelerate change by force often end badly. The French revolution, Southern secession, and communism come to mind, but the examples are many. In effect, I’ve become more tolerant of the status quo.

I wonder if my tolerance reflects the fact that the status quo has served me pretty well. I like my work, and it pays okay. Would I be as complacent about the need for change if I had a job I hated or I was barely scraping by?

I don’t know. And I’m not going to switch careers or demand a pay cut simply to find out.

What should I do? How should I evaluate my own arguments?

The same way, I think, I should evaluate any arguments: on their merits, which is chiefly to say on the evidence in favor of and against them. I should challenge with extra rigor the evidence that appeals to my own interest, precisely because it does. A story is told of a judge who was known to be scrupulously fair. A man with a lawsuit before the judge was shocked to hear his attorney insult the judge in opening arguments. Why did you do that?, the client demanded of the attorney. Because, replied the attorney, the judge is so fair he’ll bend over backward in our favor not to be biased by my insults.

This might be carrying things a bit far. Yet it's in the right spirit. Be hard on propositions you dislike, but even harder on ones you like.

I can relate to these thoughts. As I get older I lean more and more conservative. One thing to add: you say conservatives are more likely to live in a penthouse. Well, these days, at least in my experience, defenders of socialism are also likely to live in penthouses. The champagne socialists, or as they say in Latin America: esquierda caviar.

Excellent article. In my youth, (24 or so) I thought I knew how to solve the world's problems. Now, in my older age, I realize I have to investigate my own beliefs as well as those with whom I disagree. Ultimately, neither of us knows everything, but by investigating, I have found that I can come closer to the "truth" with my side either winning or losing. I've learned to listen to all points of view.

Again, thank you for your excellent posts.