Taking the fun out of history

The downside of writing it real

I recently wrote about the problem with looking for heroes in history. I said it's unrealistic to expect people to be heroes all the time. Part-time heroism is the best we can hope for. Seeking anything more leads to inevitable disillusionment.

I still think that's true. But I recognize that it's unrealistic in its own way. And it might be counterproductive to the historical enterprise.

Most people who read history do so because they have to. They are students in history classes, and the history books and articles they read are assigned. They wouldn't read them if they didn't have to, and when they get out of their history classes, they don't. Those who read history because they want to are a much smaller group. For one reason or other, they’ve acquired an interest in the past and want to learn more about it.

Contrast this with readers of fiction. Most readers of novels are not students but ordinary people looking for a good tale. They don't want realism but unrealism. The real world is all around them; they want to escape it for a few hours. The extreme genre of escapism is fantasy. Other genres of fiction—romance, sci-fi, mysteries, thrillers— are unrealistic in their own ways.

Novels sell many more copies than histories. Histories inform, but novels entertain. And when people are on their own time, most prefer being entertained. There's nothing wrong with this. It's the way people are.

The discrepancy in market size between history and fiction helps explain why people seek heroes in history. Hero worship is as beguiling as other modes of escapism, with the additional appeal of appearing to be about real life. Movies often boast: “Based on a true story.” Hero worship is like that: inspiring and true-ish.

History is more fun with heroes. Heroes give us hope, in the \same way heroes in fiction give us hope. For the time we’re reading a novel, the world is a better place. The pieces of a novel fit together more neatly than the pieces of real life. Most novels provide closure at the end: we know how things turn out. Closure has been the mantra of therapists and healing helpers for decades; it seems to be something most people want. History isn’t so considerate of our feelings.

Heroes in history are closely related to golden ages in history. If I can't believe there once was a time better than the present, how can I believe there ever will be a better time than the present?

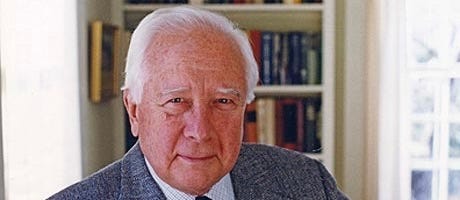

Years ago I had occasion to interview David McCullough. His book on John Adams had just come out. I noted that this book was like his earlier biography of Harry Truman, and that in each, though he fully aired the foibles of his subjects, he let readers know he greatly admired them. I asked him if he would ever write about someone he didn’t admire. He answered simply, “Why would I do that?”

I nodded, even while thinking, “Because unadmirable people can be interesting and important.” But the more I thought about his answer, the more I understood why his books were such huge hits. All McCullough’s books were thoroughly researched and engagingly written, but his books on Truman and Adams, his monster bestsellers, gave readers someone to admire as much as he did. It’s hard, while reading the books, not to feel proud about these men who led America and, by extension, about the country they led.

I realized then that I would never have the commercial success of McCullough. Even if I could match his research and writing, my take on human nature keeps me from feeling or conveying such admiration. I’ve written about Truman and Adams, and I think each man had his strengths. But each had his issues. And if I were to judge—something I decline to do anyway—I’d find the verdict less clearly in favor of the former.

I know that for most people this makes my books less fun to read. I like to think it makes them more interesting to read. But that’s not the same thing.

Maybe an adjustment can be devised, a formula found. Part-time heroes = part-time fun. Plus a portion of interesting. Would this get us closer to the McCullough magic?

I'm part of that small group that loves history, and have enjoyed both your writing and McCullough's. I find that one of the problems with "heroes" of the past is that we try to look at people of another era and force our modern sensibilities on them and judge them through modern eyes. I teach high school English, and always teach the historical context of the literature we read, and I always have to remind my students that people are a product of their time -- we can easily condemn slavery, war, and colonialism, for examples, but people born into that era knew nothing else. Thankfully, there were people who came along to right those wrongs, but we can't condemn admirable people out of hand for what we see now as their failures. All we have to do is look in the mirror and see what evils we now disregard or go along with -- perhaps not because we don't see them as evils, but we feel helpless to fix them.

One of the reasons why your readers admire your work is that you approach your subjects from a non-judgmental perspective. When I discovered your books a few years ago I had the feeling of “Yes! Finally a history writer without an agenda!”. Bravo sir