Sic semper

Booth’s final scene

He had begun to imagine the moment six years earlier. John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry had electrified the nation, sending a jolt of hope among Northern abolitionists that the battle over slavery was being joined, and a jolt of terror among Southern slaveholders to the same effect.

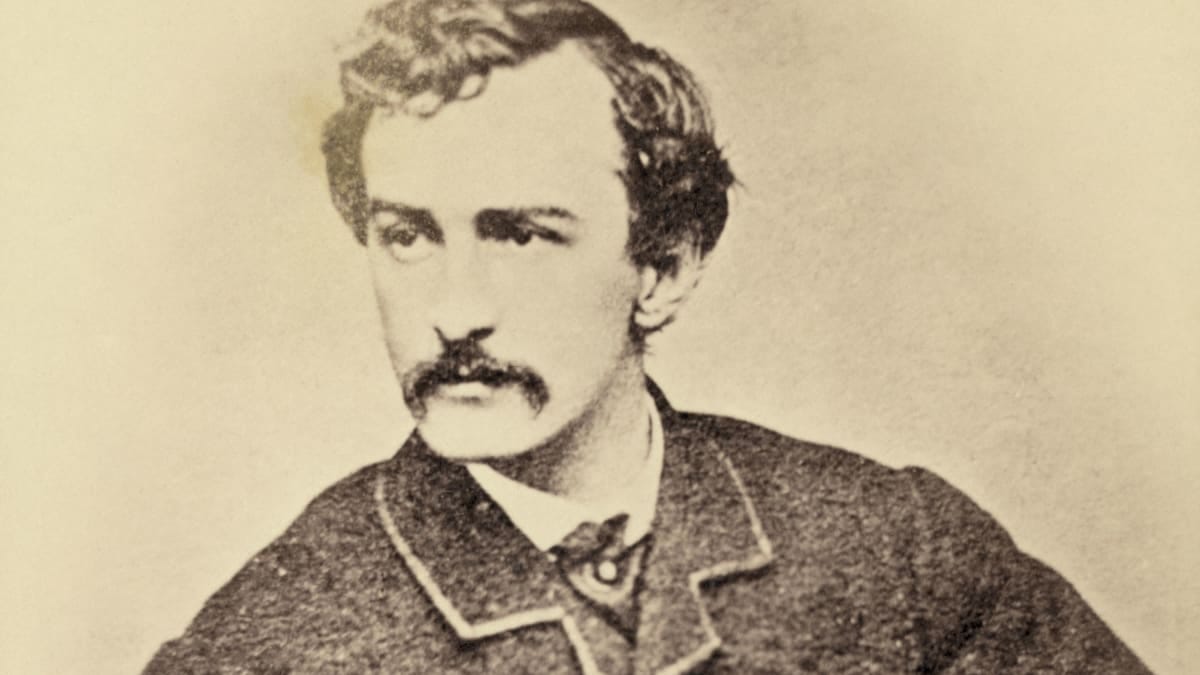

John Wilkes Booth despised what Brown stood for, but he thought the man the most compelling figure of the age. Booth was twenty-one at the time of the raid, the son of a famous actor and the younger brother of one even more famous; a desire for acclaim ran in the family. Booth had grown up in Maryland, a slave state, and learned to view slavery as a natural condition of human affairs. He resented those who tampered with it.

But the boldness of John Brown’s assault on slavery mesmerized him. He read accounts of Brown’s speeches to the court that was trying and convicting him of treason and murder, and he couldn’t help imagining himself speaking so powerfully and dramatically. “John Brown was a man inspired, the grandest character of the century,” Booth would write later. So far in his young career as an actor, Booth had played only bit parts, but he wanted more. He wanted to play the leading role, the one every audience came to the theater to see.

Booth volunteered for a militia dispatched to western Virginia to keep Brown from being rescued by fellow abolitionists. Booth later exaggerated his role in bringing Brown to justice. “I saw John Brown hung, and I blessed the justice of my country’s laws,” he wrote. “I may say I helped to hang John Brown, and while I live, I shall think with joy upon the day when I saw the sun go down upon one traitor less within our land.”

He began writing a comparably heroic part for himself on the stage of history. “I will fight with all my heart and soul, even if there’s not a man to back me, for equal rights and justice to the South,” he vowed, in a speech he envisioned himself giving. Dissenters must be crushed. “Such men I call traitors, and treason should be stamped to death and not allowed to stalk abroad in any land. So deep is my hatred for such men that I could wish I had them in my grasp and I the power to crush. I’d grind them into dust!”

Booth never found a stage on which to give this speech, but his hatred for the foes of slavery deepened as the war developed. Lincoln became the villain in Booth’s drama. “He is Bonaparte in one great move,” Booth wrote to his sister. “That is, by overturning this blind republic and making himself a king. This man’s reelection which will follow his success, I tell you, will be a reign!”

Booth increasingly likened Lincoln to Julius Caesar, and himself to Brutus. Like most Anglophones of his day—and especially those in the theater world—he knew Caesar and Brutus from Shakespeare rather than any classical text. “If the South is to be aided it must be done quickly,” he declared. “It may already be too late. When Caesar had conquered the enemies of Rome and the power that was his menaced the liberties of the people, Brutus arose and slew him. The stroke of his dagger was guided by his love of Rome.” Booth would be the American Brutus.

This Brutus struck his blow—with a pistol rather than a dagger—on the evening of April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. “I struck boldly and not as the papers say,” he wrote in his diary. The reviews of his performance—that is, the newspaper accounts of the assassination—had portrayed him as a coward who lurked in the dark and fired from cover; Booth resented the criticism. “I walked with a firm step through a thousand of his friends, was stopped, but pushed on. A colonel was at his side. I shouted Sic semper before I fired. In jumping broke my leg. I passed all his pickets, rode sixty miles that night, with the bones of my leg tearing the flesh at every jump.”

Again he embroidered. He shouted his words after shooting Lincoln; to do otherwise would have alerted Lincoln. He rode thirty miles rather than sixty, and his broken leg was a simple fracture rather than a compound one; there were no bone ends tearing at the flesh.

He took refuge in a Virginia barn. “After being hunted like a dog through swamps, woods and last night being chased by gun boats till I was forced to return wet, cold and starving, with every man’s hand against me, I am here in despair. And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for, what made Tell”—William Tell, a Swiss patriot—“a hero. And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”

His days, his minutes perhaps, were numbered. “So ends all. For my country I have given up all that makes life sweet and holy, brought misery on my family, and am sure there is no pardon in heaven for me since man condemns me so.” Yet he wouldn’t have acted differently. “I do not repent the blow I struck. I may before God, but not to man.”

In the pain of his broken leg, his lack of sleep and food, he rambled. “I think I have done well, though I am abandoned, with the curse of Cain upon me. When if the world knew my heart, that one blow would have made me great, though I did desire no greatness. Tonight I try to escape these blood hounds once more. Who can read his fate? God’s will be done. I have too great a soul to die like a criminal. Oh, may he, may he spare me that and let me die bravely. . . . I do not wish to shed a drop of blood, but I must fight the course. ’Tis all that’s left me.”

The end came unheroically. After Booth refused to surrender, his pursuers set fire to the barn. One shot Booth as the assassin fled the flames. He lingered for three hours before dying.

Not even Shakespeare could have done much with that.

Very interesting!