Samuel Slater and the purloined IP

When America was the poacher

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that tech firms in China are poaching engineers and scientists from companies in other countries by offering salaries as much as three times what they’re currently making. The practice isn’t illegal in the United States and Europe, though it’s frowned upon by governments and companies and distrusted by many potential poachees. Taiwan and South Korea have passed laws against it, citing the need to protect intellectual property.

The protection of powerful secrets has roots deep in human history and mythology. Adam and Eve ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and were banished from Eden. Prometheus stole fire from Olympus and was condemned to eternal punishment. China long guarded its secrets of silk production from foreigners, but agents enlisted by the Byzantine emperor Justinian in the sixth century smuggled silkworms out in hollow canes. Gunpowder remained a Chinese monopoly longer, until its formula was acquired by Muslim agents in the thirteenth century.

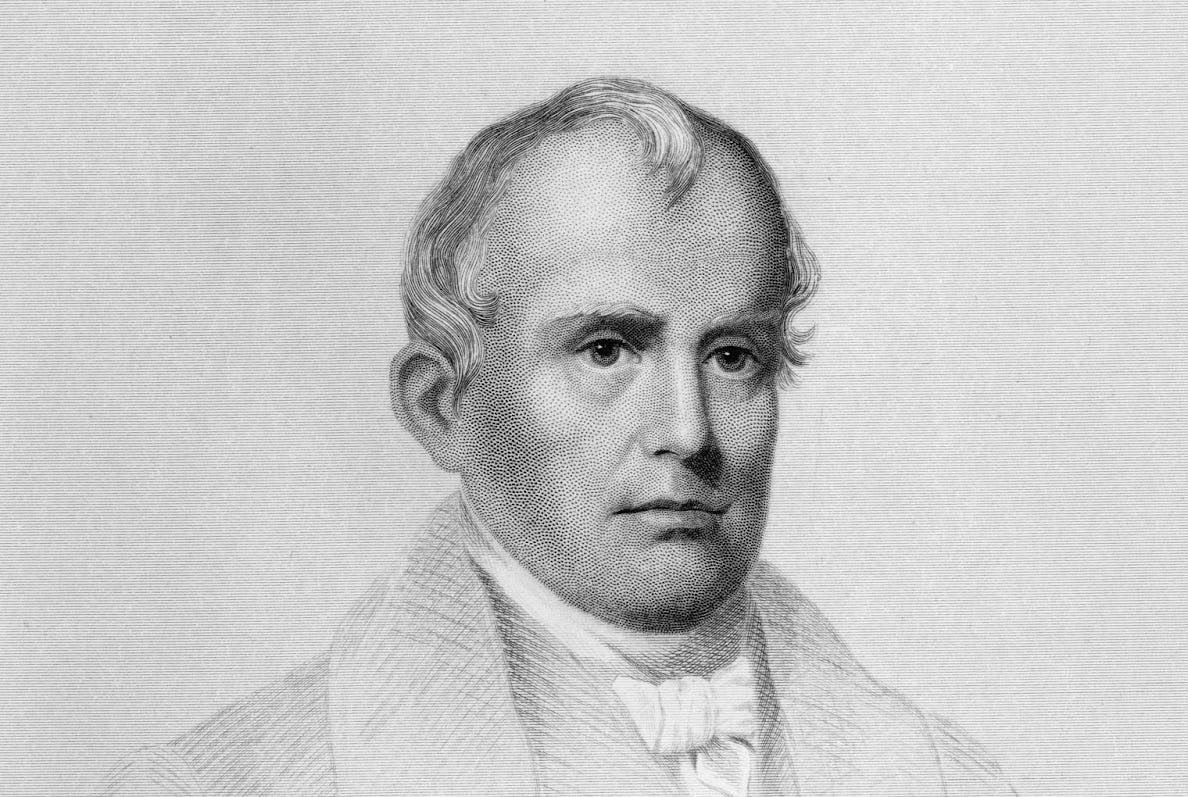

The industrial revolution multiplied trade secrets even as it increased the temptation to steal them. Samuel Slater was born in England in 1768, and grew up in Derbyshire, the center of the emerging cotton textile industry. His father died when Sam was in his early teens, and the lad was apprenticed to a cotton spinner who operated the latest machinery designed by Richard Arkwright.

Slater had a head for machinery and an eye for his future, which seemed to him less promising in England than in America, independent following the American Revolution. Slater read in a newspaper from Philadelphia that an American society for promoting manufactures was offering a bounty to anyone with knowledge of the latest textile machinery. “This convinced him that America must be very bare of every thing of the kind, and he prepared himself accordingly,” wrote a Slater associate who became his first biographer. Slater remained with his employer beyond the term of his apprenticeship, memorizing the parts and functions of the equipment he had been trained on.

Britain at this time led the world in textile technology, and the British government was determined to protect its lead. The government didn’t recognize any general right of emigration, and it outlawed the departure of people with expertise such as Slater was acquiring. Accordingly he concealed his intentions from everyone, even his mother. He dropped in at the family home to pick up some clothes, saying he was merely traveling to London. This was the last time she ever saw him.

“He was aware that there was danger of his being stopped, as the government restrictions were very severe,” Slater’s biographer wrote. “The officers were very scrupulous in searching every passenger to America.” Slater presented himself as a farmer rather than a machinist. He worried a bit about his apprentice papers, which would serve as his letter of recommendation in America. But he hid them and the officers’ search was foiled.

Slater arrived in New York in November 1789. He quickly learned that southern New England was where America’s textile industry was taking root, on the fall line where rivers plunged downward with sufficient power to turn waterwheels and the machinery attached to them. He relocated to Pawtucket, Rhode Island—a city whose name derived from an Algonquin word for “river falls”—and formed a partnership with a cotton spinner there.

The business thrived, based as it was on the latest secrets of English technology, which none of Slater’s American competitors could match. Nor did he worry about competition from Britain, since that country was locked up with France in a series of wars that filled the next quarter-century.

Slater’s business benefited as well from Eli Whitney’s new cotton gin, which greatly reduced the cost of Slater’s principal raw material, cotton fiber. During the 1790s Slater opened mills in several other New England towns.

What Slater had done to Arkwright, Slater’s competitors eventually did to him. The nascent American patent system afforded insufficient protection to prevent rival cotton spinners from hiring away Slater’s workers and picking their brains. By the time Anglo-American trade returned to normal after the final defeat of Napoleon—and after the War of 1812 between America and Britain—the American textile industry counted hundreds of manufacturers productive enough to hold their own in competition with Britain.

This didn’t keep them from seeking tariff protection, which padded their profits—and which provoked South Carolina nearly to secession. The crisis was resolved peacefully when the textile men and their fellow manufacturers accepted a phaseout of the tariffs.

Tariffs again are in the news, along with the efforts to protect IP from poachers. Today America is playing defense, as Britain did in the time of Samuel Slater. Maybe America will have better luck than Britain did. No one can memorize the design of a computer chip the way Slater memorized Arkwright’s machinery.

But ideas are hard to embargo, and humans venture where opportunity beckons.