Sam Houston walks at midnight

And makes his painful choice

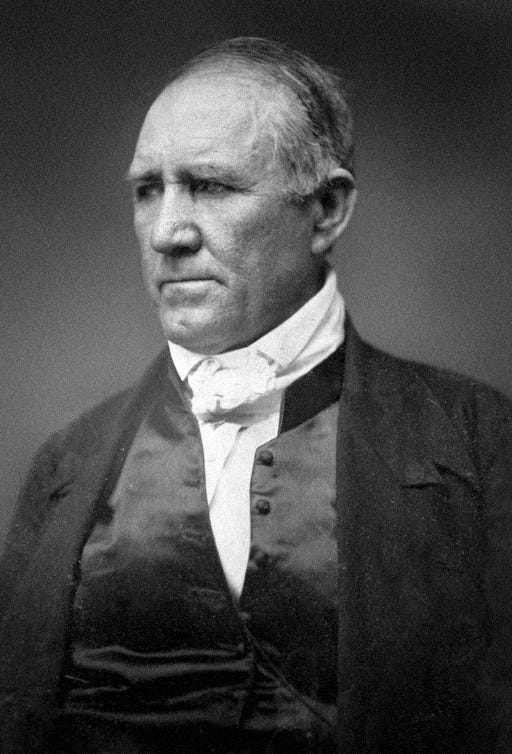

Sam Houston appreciated irony, although it wasn't his favorite metier. He was a straightforward man at heart, a believer that right triumphs in the end. But this belief grew harder to sustain the older he got.

No one had been more responsible than Houston for the creation of modern Texas. Stephen Austin had pioneered the colonization of Mexican Texas by American settlers, but Austin had been slow to embrace the idea that Texas should be independent of Mexico. By the time he did, Houston was the one Texans looked to for leadership.

Houston guided a motley Texas army to victory over the Mexican army of Antonio López de Santa Anna. Texans had rewarded Houston by making him president of the Texas republic. Houston capitalized on a longstanding relationship with Andrew Jackson, his mentor and surrogate father, to arrange the annexation of Texas to the United States. Texans again rewarded Houston, by making him their senator and sending him to Washington. When he tired of life in the national capital and wished to return home, they made him governor of the state.

It was as governor that he felt the earth eroding beneath his feet. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 inflamed secessionists throughout the South. The secessionist wave swept west from South Carolina, reaching Texas in early 1861. Its rising waters caused the Texas legislature to summon a secession convention. The convention endorsed secession, and now the waters were lapping at Houston’s feet in the governor’s mansion on an adjacent hill.

Houston yielded nothing to any man in defending the rights of states to exercise their constitutional prerogatives. But he drew a sharp line between states’ rights and secession. The latter, far from preserving states’ rights, would destroy them, he said. And it would destroy those who attempted it. Houston stood with Jackson in judging the Union the great bulwark of American democracy. If the Union failed, democracy would fail too.

“It has been my misfortune to peril my all for the Union, so indissolubly connected is my life, my history, my hopes, my fortunes with it,” he told the secessionists. “And when it falls, I would ask that with it might close my career, that I might not survive the destruction of the shrine that I have been taught to regard as holy and inviolate since my boyhood. I have beheld it, the fairest fabric of government God ever vouchsafed to man, more than half a century. May it never be my fate to stand sadly by gazing on its ruin.”

But now he was asked to do just that. Indeed, he was ordered to do so. The convention wrote a new constitution for Texas, attaching the state to the Confederacy. It required that all Texas officials swear loyalty to the Confederacy.

An emissary brought the demand to Houston at eight at night. The convention insisted on an answer at once. Houston told the emissary the convention would have to wait. It would get his answer in the morning.

Houston knew what the answer would be, but he wanted time to reflect. Two battle wounds reminded him of the sacrifices he had made for his country and his state. At Horseshoe Bend in the War of 1812, he had fought on behalf of the Union against Britain and Britain’s Indian allies; impaled by an arrow in the thigh, he had nearly died from loss of blood. At San Jacinto in the Texas war against Mexico, he had taken a musket ball to the ankle.

The old wounds ached this night, as Houston paced the floor of the governor’s house. One step told what he had given to the Union; the next step recalled what he had given to Texas. Until now he had been able to reconcile his country and his state, but no longer. He had to choose, and the choosing made the wounds ache the more.

The next day he delivered his decision, not to the convention, which he refused to acknowledge, but to the people of Texas, in his last message as their governor.

“Fellow citizens,” he said, “In the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by this convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the constitution of Texas, which has been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies . . . I refuse to take this oath.”

History weighed upon him, as the present broke his heart.

“I have seen the patriots and statesmen of my youth one by one gathered to their fathers, and the government which they had created rent in twain; and none like them are left to unite it once again. I stand the last almost of a race, who learned from their lips the lessons of human freedom.”

Houston packed his bag and left Austin, lamenting what secession would bring. He retired to East Texas and lived just long enough to learn of the Confederate defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, which confirmed his belief that secession was doomed from the start. He took no comfort in knowing he had been right.

My favorite Sam Houston anecdote (and like many if not most historical anecdotes probably apocryphal) is the one when he became a Christian in midlife. The preacher took him down to the river for baptism. When the ceremony was over, Houston asked the pastor "now what does this mean?" The pastor replied: "It means your sins have been washed down the river and into the ocean." Houston then said: "I pity all those poor fish."