"Today there are two great peoples on earth who, starting from different points, seem to advance toward the same goal: these are the Russians and the Anglo-Americans,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1835. The United States was expanding westward across North America to the Pacific Ocean, while Russia was advancing eastward to the Pacific across Asia. “All other peoples seem to have almost reached the limits drawn by nature, and have nothing more to do except maintain themselves, but these two are growing," Tocqueville said.

For both countries, growth entailed challenge, yet the challenges facing them differed. “The American struggles against obstacles that nature opposes to him; the Russian is grappling with men. The one combats the wilderness and barbarism; the other, civilization clothed in all its arms. Consequently, the conquests of the American are made with the farmer’s plow, those of the Russian with the soldier’s sword. To reach his goal the first relies on personal interest, and, without directing them, allows the strength and reason of individuals to operate. The second in a way concentrates all the power of society in one man.”

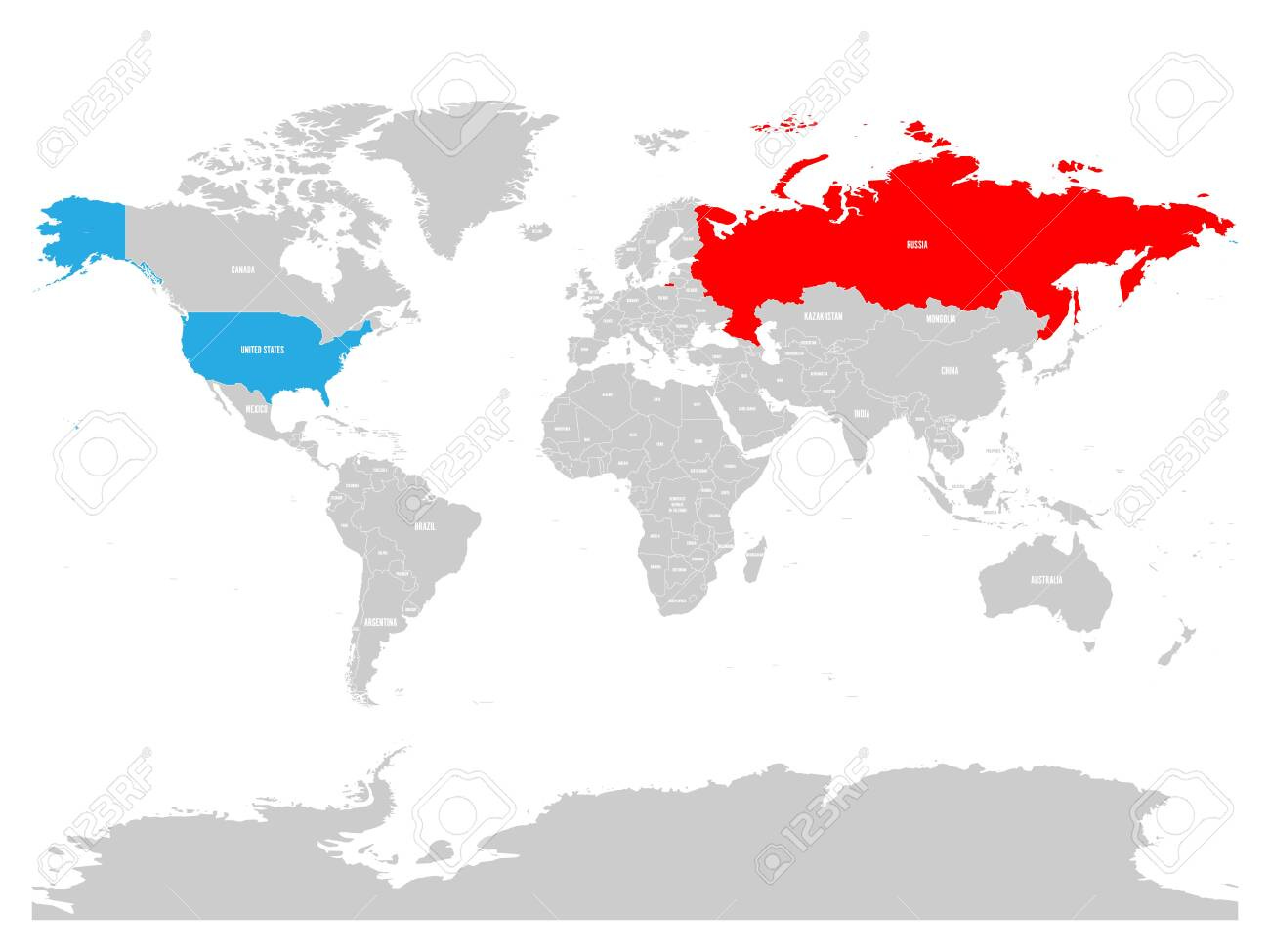

Democracy suited America's purposes, and autocracy Russia's. Yet the histories of the two countries would have similar ends. “Their point of departure is different, their paths are varied; nonetheless, each one of them seems called by a secret design of Providence to hold in its hands one day the destinies of half the world.”

Tocqueville could not have seen that America and Russia would be squaring off over Ukraine almost two centuries later. Nor could he have predicted the violent twists and turns of world history in the interim. But he wouldn't have been surprised that the great democracy of North America and the great autocracy of the Eurasian heartland retained sufficient strength and ambition to shake the world with this latest round of their competition.

The strength of both came from the abundant natural resources at their command. The industrial revolution of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries allowed smaller countries—Britain, Germany, Japan—to leverage ambition into passing prominence, but each eventually faded. The continental expanse of America and Russia supported large populations that let them crush or outlast their rivals.

In the early twenty-first century, China emerged as a potential rival to both. But China had yet to grow into its strength. Dominating its neighbors did not come naturally.

For a decade at the end of the twentieth century, Russia's strength and ambitions had seemed to be failing. It shed its inner and outer empires—the Soviet Union and the cordon of coerced allies in Eastern Europe—without even making a fight.

Russia's ambition revived with the ascent of the latest in the long line of czars and commissars. Vladimir Putin never accepted that Russia must resign itself to second-rate status. Russia's strength ticked up with a rise in world oil prices, which compensated for deficiencies in the rest of the Russian economy.

America's strength had suffered too, in a comparative sense. America's apogee came in 1945, when its industrial might was equal to that of the rest of the world combined. The world closed the gap dramatically by the end of the millennium.

America's ambitions sagged commensurately. American voters in 2016 installed a president who rejected essential premises of the American-led democratic order. Donald Trump drew inspiration and a campaign slogan from the isolationist America First movement of the 1930s.

Putin misread the change in American attitudes, just as many Americans misread the decline in Russian ambitions. Putin's invasion of Ukraine conjured fresh images in American minds of the Russian expansionism combated by U.S. policy during much of the twentieth century, and it injected new life into American aspirations for world leadership. In the name of democracy, Joe Biden rallied opposition to this latest eruption of Russian autocracy.

Perhaps America would prevail in Ukraine; perhaps Russia. The Tocquevillean heavyweights weren’t what they once had been, but for now, as for much of the previous two centuries, the world awaited the outcome of their struggle.

Are you implying that Trump’s America first policy is directly responsible for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? I would counter that it is Biden’s explicit weakness on the heels of Obama’s capitulation on Crimea that emboldened Putin. C’mon Dr Brand, your bias is showing big time. Blaming the USA for the worlds ills, especially the rise of dictators is a poor substitute for rational thought. As a people we have our faults certainly but the pluses still way outweigh the negatives even with weak leadership. But, thanks for allowing alternative opinions