Rules

The ties that bind

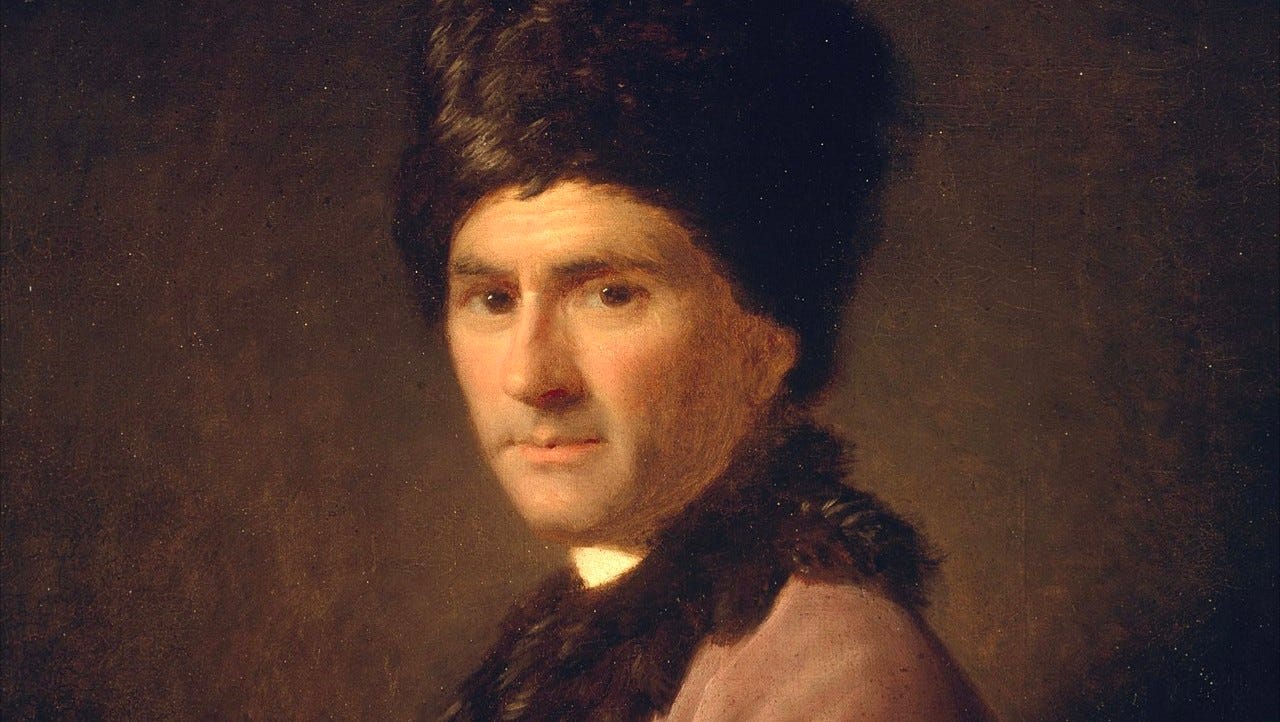

“Man is born free but is everywhere in chains.”

Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote these words at the beginning of The Social Contract. At the time of the writing, in the 1760s, some of the chains were physical. Political prisoners languished in the Bastille in Paris and comparable facilities elsewhere. Slave coffles marched unfortunate souls from their homes in Africa to the coast to be shipped in chains to markets in Europe, Asia and America.

But the chains that interested Rousseau more were the metaphorical chains of habit and custom that bound society together. In an idealized state of nature, each man was a law unto himself. But as soon as men began living in groups, rules emerged to govern their behavior. These rules determined who owned what, who mated with whom, who did which jobs, who deferred to whom, and so on. How the rules were established varied from society to society and over time within each society. Different rules were differently enforced. Rule breakers might be shunned or banished. They might be deprived of property or privileges. But the essence of the rules was to limit the ability and inclination of individuals to act as they chose. The rules were chains upon man's freedom.

In giving up freedom, humans gained security. This was the bargain at the heart of the social contract. The question in any society was the question in any bargain: Is the prize worth the price? Rousseau thought not. He looked around the France of the ancien regime and concluded that most men and women gave up far more in freedom than they got back in security. Indeed many were less secure—from their ostensible protectors in government even—than they would have been in a state of nature.

Rousseau understood he was speaking theoretically. There never was a state of nature in which individuals lived by themselves. Humans are a social species. Our society antedates our species, as the social nature of our anthropoid cousins reveals. Rousseau lived before Darwin and so wouldn't have thought in evolutionary terms. Yet everyone knew that humans cannot live outside society. An abandoned infant dies within a day or two. An adult cast into to the wilderness is lucky to last a month.

Moreover, the rules of our societies go far beyond relations between governors and governed. And they make us who we are as individuals as much as they define our places among other individuals.

Many of our rules emerged without conscious thought. Each human language consists of sounds every human could make but arranged and interpreted according to rules peculiar to each language group. Each language echoes the world in a unique way. The speakers of that language perceive and describe the world distinctively.

The rules that govern relations between the sexes might have emerged unconsciously. But over generations they have been shaped to serve deliberate purposes. Some cultures are patriarchal. Some are matriarchal. Some are monogamous, some polygamous. The differences reflect, among other things, relative numbers of men and women in a culture at any given time, and disparities of wealth between different groups within the culture.

Many rules are arbitrary and apparently trivial. But the appearance of triviality can be misleading. In Austin, where I live, swimmers and sunbathers at Barton Springs include bare-breasted women. A chain link fence separates the pool area from surrounding Zilker Park. The fence is transparent, so strollers in the park have no difficulty seeing the sun bathers. No one takes anything amiss—until a topless woman steps outside the fence into the park. Going topless in Austin is not illegal. It simply isn't done. No one would do anything to a woman who flouted the rule. But what is perfectly innocent, acceptable behavior inside the fence constitutes exhibitionism thirty feet away on the outside.

In Russia in the 17th century, Christians became deeply divided over whether the sign of the cross should be made with two fingers or three. Theology was involved, of course. But two-fingered crossers came to bad ends among the three-fingered, and vice versa. What seemed trivial to outsiders mattered a great deal to those on the inside. Rules are like that.

Young ladies in certain sectors of American society used to be sent to finishing schools, where they would learn which fork was to be used with which dinner course, and similar customs. A faux pas could reduce a girl's value in the marriage market and change her life.

Financial speculators during the Gilded Age did all they could to acquire information about the likely direction of share prices of particular companies. Such information could be leveraged into handsome profits on the stock market. But in the 20th century, the rules were changed to forbid insider trading. People now went to prison for doing what their grandfathers had done quite legally.

Bribery is illegal in most political systems. But what constitutes bribery varies widely. Campaign donations don't count in America. Other countries forbid campaign donations precisely because they suggest the kind of quid pro quo bribery consists of.

One's place in society often depends on one's willingness to play by the rules. To break the rules, even to point out the arbitrary nature of many rules, is to risk loss of status and perhaps freedom and safety. Know and observe the rules—stay inside the fence at Barton Springs—and you're okay, you're one of us. Ignore the rules, go outside the fence, and you're part of some other, potentially rival clan.

Rousseau fell into the trap he described. His writings got him in trouble with authorities who made the rules about what might be properly said and written. He moved around Europe one step ahead of the law. Finally in Paris he neglected an essential rule of the road in the French capital: Pedestrians must give way to carriages belonging to the rich and powerful. One such carriage careened down a narrow street with the owner’s Great Dane galloping alongside. Rousseau dodged the carriage but not the dog. His head hit the cobbles. The injury did lasting brain damage that contributed to his death two years later.

I mistakenly pressed “Send” instead of “Return” before I was through editing this comment. I was not able to properly encase in quotation marks the words of others that appear at the base of the statute. Nor was I able to properly punctuate it where needed. My apologies.

It should have continued: The plaques around the statute note that “[t]hese three - Dobie, Bedichek, and Webb - strove to create a vibrant and distinctive intellectual climate in Texas, and their influence reached far beyond the state. This monument has been erected to celebrate their friendship, their enlightened spirit and their love for Barton Springs.”

The Walter Prescott Webb plaque quotes him as saying “Civilization shouts, gives orders, writes rules, puts man in institutions, and intimidates him with a thousand irritating directives. In return it offers him protection, soul salvation, and a living if he can find it. Nature looks down on him and broods in silence. Its noises of running streams and wind in the trees are its own, not directed at but soothing to him because he heard them before he heard the noises of civilization. Walter Prescott Webb, 1888-1963.”

This quote I think is relevant to Professor Brands’ essay.

The Roy Bedichek plaque quotes him as saying “I wish you might be here and go with me on a sunny afternoon to Mt. Bonnell or up Barton Creek. Everywhere it is beautiful. I think we could settle most of the world's problems to our satisfaction. And a thousand years from now friends such as we will, wander over these same hills inhaling the same scents and feasting their eyes upon the same beauty, and maybe the identical matter that composes our bodies now will nourish the worm that feeds the mockingbird whose songs will go thrill out over the green fields. Roy Bedichek, 1878-1959.”

This captures my own feelings about this place, over a half century after Prof. Bedichek’s death.

So accept the above for what it is, a very rough draft.

However, I wish to add a historical footnote that, to the best of my recollection, the phenomenon of bare breasted female swimmers and sun bathers did not occur at Barton Springs until 1969 or 1970, after Woodstock. But as a respected friend of mine, who while ushering her young children and their cousins from the shallow end, where those bathers usually spread their towels, to the middle and deeper end which was more traditional, and telling them not to stare, was told by one of her young wards: “Aunt ___. If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.”

That 20th century juvenile philosophy, spoken some 200 years after Rousseau wrote, says something. After 50 years of first hearing the story, I am still trying to figure out why it resonates.

I am surprised that this essay of Professor Brands has not provoked a single comment although, as I write, there are at least 10 “likes.” It brings to the reader’s mind 18th century philosophical thought surely on the minds of our Founding Fathers as they crafted our great documents in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. It brings 18th century French and Russian history to the front, with a little theology thrown in. It latches on to American economic history, securities law, criminal and election law. And perhaps draws from a little anthropological sociology. Yet, no comments. So I will.

I do because its argument uses as an example one of my favorite places, Barton Springs. I learned to swim there.

Outside the Bathhouse, outside the chain link fence, facing away from the pool, is a sculpture created by Glenna Goodacre, known as “Philosopher’s Rock,”depicting a shelf of limestone inside that chain link fence that once rose out of the glittering water at the edge of Barton Springs, where the naturalist Roy Bedichek and the chronicler and folklorist J. Frank Dobie and their friend, historian Walter Prescott Webb (who was not a swimmer), sat in the sun and talked about everything from classic works of literature to tales of lost Spanish treasure. The plaques around the statute note that “[t]hese three - Dobie, Bedichek, and Webb - strove to create a vibrant and distinctive intellectual climate in Texas, and their influence reached far beyond the state. This monument has been erected to celebrate their friendship, their enlightened spirit and their love for Barton Springs. Sculpture by Glenna Goodacre Site setting by Stephen K. Domigan

Walter Prescott Webb Plaque) Civilization shouts, gives orders, writes rules, puts man in institutions, and intimidates him with a thousand irritating directives. In return it offers him protection, soul salvation, and a living if he can find it. Nature looks down on him and broods in silence. Its noises of running streams and wind in the trees are its own, not directed at but soothing to him because he heard them before he heard the noises of civilization. Walter Prescott Webb, 1888-1963 (Roy Bedichek Plaque) I wish you might be here and go with me on a sunny afternoon to Mt. Bonnell or up Barton Creek. Everywhere it is beautiful. I think we could settle most of the world's problems to our satisfaction. And a thousand years from now friends such as we will, wander over these same hills inhaling the same scents and feasting their eyes upon the same beauty, and maybe the identical matter that composes our bodies now will nourish the worm that feeds the mockingbird whose songs will go thrill out over the green fields. Roy Bedichek, 1878-1959