Religions and republics

Friends or foes?

Do religiously minded people make good citizens of a republic?

Benjamin Franklin thought they did. Though not observant himself, Franklin donated money to each of the religious denominations in Philadelphia. He believed that the practice of religion conduced to social order. The moral codes of the religions he knew helped make people solicitous of the welfare of others, and this tended to make them good citizens.

If Franklin was right, his practice can be worth extrapolating. Like Franklin, governments need not choose among religions, but they could support them all, to the benefit of the community as a whole.

But maybe Franklin wasn't right. Perhaps his Philadelphia sample was unrepresentative of religions generally. Philadelphia was a famously tolerant city, having been founded as a refuge for Quakers, a sect despised and distrusted in Anglican England. People who moved to Philadelphia understood its nature and presumably were inclined to be tolerant themselves. When they established churches, meeting houses and synagogues, these would be tolerant.

Philadelphia was unusual, even in British North America. A principal reason Franklin left the Boston of his birth was that he couldn’t abide the Puritan theocracy there. Franklin knew enough history to appreciate the irony that though the Puritans had fled England to practice religious freedom in America, they didn’t allow religious freedom to others, instead persecuting and banishing dissenters from their own orthodoxy.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison held a different view from Franklin’s on the relation between religion and republicanism. Rather than seeing religion as reinforcing republicanism, Jefferson and Madison perceived religion as a threat. Some of this had to do with the fact that Jefferson's Virginia, unlike Franklin's Philadelphia, took sides in the religious debate. The Anglican church in colonial times, and then the Episcopalian church after independence, was the established church in Virginia. Taxpayers supported its activities and paid its ministers. Laws favored members of the established church to the disadvantage of Baptists, Presbyterians and others.

Madison insisted, successfully, that George Mason write a provision guaranteeing freedom of religion into the Virginia Declaration of Rights, and later himself included a similar provision in the First Amendment of the Constitution. Jefferson went further, demanding that the Episcopal Church be disestablished in Virginia. For his pains he was called an atheist and a corrupter of youth. But he persisted and finally succeeded. On his tombstone he specified the listing of the three accomplishments of which he was proudest: drafting the Declaration of Independence, founding the University of Virginia, and writing the statute of Virginia for religious freedom.

The Virginia statute was necessary because at that time the First Amendment was not understood as applying to the states. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” it declared. States could do so at their pleasure. And some did. But the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment extended the federal ban to the states in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This should have ended the debate about the role of religion in the American republic. It probably would have if all Americans had been as tepid about their religious views as Franklin's Philadelphia neighbors. But time and again state legislatures, and occasionally Congress, tried to bootleg religion into laws under other guises. Sometimes Congress and the states worked together. The Eighteenth Amendment didn't mention religion in forbidding most things relating to alcohol. But the campaign behind it had often been cast as a defense of Protestant values against novel practices introduced by Catholics.

The legislature of Oregon, when under the influence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, approved a statute effectively outlawing Catholic schools. The Supreme Court overturned the law, but the memory persisted in the state. As a child in a school operated by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, who happened to be the lead plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case, I often heard the tale of their brave defense of religious freedom.

Recently various states have considered or approved laws channeling public education funds to private schools, including religious schools. Groups promoting “Christian nationalism" have become increasingly active against what they see as secularism and an unacceptable neutrality among religions by the American government.

The reason abortion is such a divisive issue is that, for most opponents, it involves deeply held religious views about the soul and its connection to the divine. Other issues can be compromised, but most religious views can't.

The tension between religion and republicanism is inherent and unavoidable. Republicanism is fundamentally secular, while religion is, well, religious. Jesus noted the difference in telling his followers to render to Caesar the things that were Caesar’s and to God the things that were God’s. On the testimony of Matthew, the evangelist who quoted him on this, Jesus wouldn't have had difficulty with the First Amendment. But his followers aren’t always so open-minded.

It would be surprising if they were. Religions claim access to higher truth than is available to earthly institutions. Most claim priority on the loyalties of their followers. This was long a hurdle for American Catholics, who were suspected of being more loyal to the pope in Rome than to the government in Washington. John Kennedy was able to allay the suspicion sufficiently to squeeze past Richard Nixon in 1960, but two generations would pass before the election of the second Catholic, Joe Biden.

Religions by their nature are divisive. Some state explicitly that infidels are going to hell; others imply it. A few people genuinely accept that all religions are equally valid, but they are greatly outnumbered by the true believers.

Which is precisely as things should be. If you believe something, especially on a subject like religion, you ought to believe it truly. Different denominations might agree to a tolerant peace of exhaustion, as happened in Europe at the end of the wars of the Reformation. Or a persecuted minority might prescribe toleration in memory of its own suffering, as happened in Franklin's Philadelphia. But to expect people who take religion seriously to separate it from their politics is to expect too much.

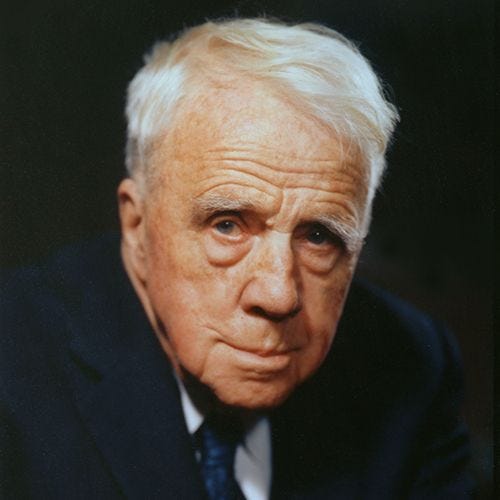

This creates a problem for people who take republicanism seriously. Madison and Jefferson tried to create a wall between church and state, and succeeded. But as Robert Frost said, there's something about a wall that wants it down. In this case it's religion. Many religionists wouldn't be true to their faith if they didn't chip away at the wall now and then. Republicans have to keep their mortar and stone handy.

Excellent analysis. Although the character in "Mending Wall" pontificates about walls, it's he who sees his neighbor as a "savage armed."