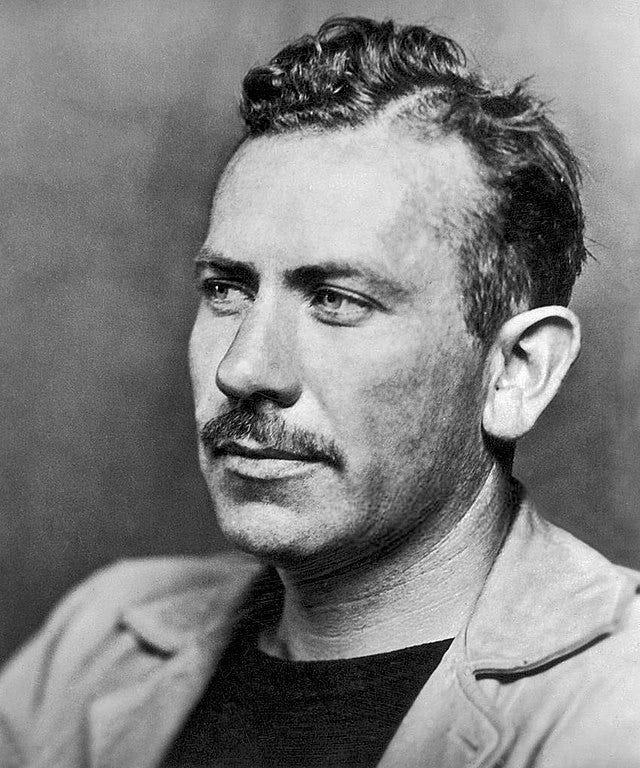

“The Salinas River was only a part-time river,” John Steinbeck wrote near the beginning of East of Eden. “The summer sun drove it underground. It was not a fine river, but it was the only one we had and so we boasted about it — how dangerous it was in a wet winter and how dry it was in a dry summer. You can boast about anything if it's all you have. Maybe the less you have, the more you are required to boast.”

William Shakespeare touched a similar theme in Hamlet. “The lady doth protest too much, methinks,” says Queen Gertrude of a character in a play-within-the-play who thereby betrays insincerity.

The wizard in L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz embodies the spirit of compensatory boasting. Toto accidentally reveals that the wizard is a humbug, pretending to have great powers when he has nothing of the sort.

Vince Lombardi, the legendary National Football League coach for whom the Super Bowl trophy is named, detested boasting or on-field celebration. “Act like you've been there before," he ordered players tempted to show excitement after reaching the end zone for a touchdown.

People in other countries have long rolled their eyes at Americans' boastfulness. Alexis de Tocqueville found a great deal to like in America, yet one thing drove him crazy. "A foreigner will gladly agree to praise much in their country,” Tocqueville wrote. "But he would like to be allowed to criticize something, and that he is absolutely denied."

Americans have operationalized their boastfulness in terms of “American exceptionalism” and "manifest destiny.” The former concept asserts that rules that apply to other countries don't apply to the United States. The latter declares that God has smiled peculiarly on America, giving it the right to extend American values and institutions across neighboring territory.

The Monroe Doctrine was an early implementation of Americans’ self-proclaimed greatness. President James Monroe, at the urging of Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, in 1823 presumed to speak for the rest of the Americas in warning Europeans to keep their hands off.

In itself, the Monroe Doctrine didn't claim anything for America which other powerful countries hadn't claimed for themselves. The Romans declared and defended the boundaries of the Roman empire. The Mongols, the Ottomans and the British did the same for their empires. But none of those imperialists had founded their systems on a natural right to self-government.

Manifest destiny was even more annoying. Again, the great-power practice of taking the territory of neighbors was as old as history. And, to be sure, conquerors sometimes claimed divine sanction. The Israelites did it. The Muslims did it. The Holy Roman Empire did it. But America's Constitution created a republic that set God to the side. And democracy, the political system they were spreading, by its nature can't be imposed but rather must be embraced.

Americans’ high self-regard has inspired them to attempt noble things. Woodrow Wilson in 1917 called upon his compatriots to wage a war “to end all wars.” Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s sent 500,000 American soldiers to Southeast Asia to preserve the national identity of South Vietnam. George W. Bush included the planting of democracy in the Middle East among his reasons for war against Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 2003.

But between the trying and the achieving has often been a big gap. In each of the cases above, American efforts were expensive, unavailing and in some respects counterproductive.

Our current president promises to make America great again. If he genuinely succeeds, all should applaud him. At its best, America has been a blessing to the world — a beacon of freedom and an engine of prosperity.

But the MAGA movement would be more convincing if the members and its leader talked less about greatness and did more to accomplish it — if they took off their caps and rolled up their sleeves.

The test will be whether they’re willing to leave to disinterested parties the judging of America's greatness. Talk is cheap, boasting cheaper.