Property rights

Natural or synthetic?

Where do property rights come from? Who determines their nature? What purposes do they serve?

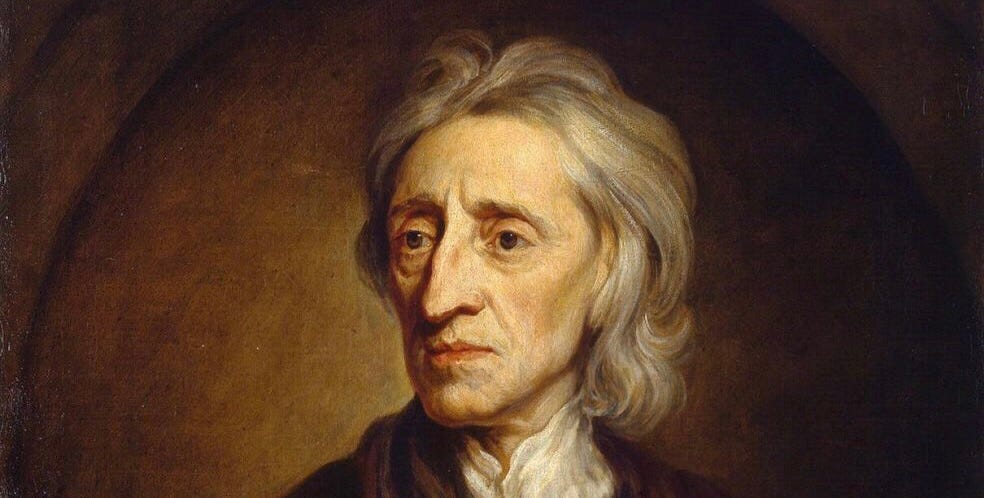

To John Locke is attributed the formulation of natural rights as consisting of life, liberty and property. Life and liberty were easy to explain as arising with the individual. Before a man is born, he has no life; no one had a previous claim on that life. When the man dies, the life vanishes with him; there is no life claim to pass on. Furthermore, life cannot be alienated. A man cannot transfer his life to someone else.

Liberty can be dealt with similarly. Before a woman is born, her liberty does not exist. She didn’t acquire it from someone else; it came into being with her. When she dies, her liberty goes out of existence. She cannot alienate her liberty by selling or giving it to someone else. She can be deprived of liberty—by enslavement, for example—but her enslaver doesn’t gain liberty by taking away hers.

Property is different. The most common form of property in Locke’s day, as for millennia previous, was land. The land existed before any particular individual was born. It would exist after that individual died. Land—or at least the use of it—can be alienated: bought, sold, given, stolen.

Additionally, the rights to life and liberty are negative rights, requiring simply that others leave their possessors alone. The right to property is a positive right, requiring the acquisition of property. Moreover, the acquisition of property by one person entails the dispossession of someone else. The creation of a new human life doesn’t deprive another human of life, nor does the addition of a free person to the human race subtract from human liberty elsewhere. But I acquire an acre of land by taking it from you or another.

Other forms of property are somewhat different. If I plant and harvest a crop of wheat on my acre of land, my labor has produced something that did not exist before. Likewise if I write a song, my labor has produced something that didn’t already exist.

Because property rights are different than other rights, and because there are different kinds of property, societies have devised different sorts of rules to deal with property. In the English tradition, the freehold was the standard form of property ownership. Rooted in claims to land, the freehold gives absolute ownership over land and improvements on the land to the owner, and does so in perpetuity. The freeholder can buy or sell the land at will, and can bequeath it at the time of death. With certain exceptions, the freeholder can keep others off the land. In some jurisdictions, including several states of the United States, the freeholder can employ lethal force to keep others from trespassing.

Much of the philosophy of the freehold has been extrapolated to forms of property besides land. Material wealth of all kinds can be bought, sold and bequeathed. Intellectual property—trademarks, patents, copyrights—can be bought, sold and bequeathed. Trademarks are perpetual, unless abandoned by the owner; patents and copyrights are limited in duration.

Owners of property understandably want to defend their property rights. They have often claimed that such rights come from nature or from God. The implication is that mere humans must keep hands off. In conservative parts of the United States, property rights are rarely mentioned without being described as "God-given."

But God neglected to put his name on the deed. In reality, property rights are human-constructed. Every society, every political system, has to choose for itself what the construction should look like. Some societies have not allowed individuals to own land; all land is communally held. These include traditional societies such American Indian tribes, but also revolutionary societies like the Soviet Union and Maoist China, and religious orders and cults. Other societies encourage freeholding, as encouraging liberty, self-reliance and productivity.

The handling of intellectual property is instructive. A patent grants a monopoly to the patent holder for a set number of years. The monopoly encourages investment of time and effort in the invention of new products, but the limited duration ensures that the new product will eventually be available to society at large. New pharmaceuticals are expensive to discover and shepherd through the approval process; the companies that make them recoup their costs and earn a profit during the period of the patent. When the patent expires, other companies, which didn’t incur the development costs, can make a generic version and sell it for less.

The society, acting through government, has to find a balance. If the patent period is too short, few new medicines will be discovered, because companies won’t think they can make a sufficient return on their investments. If the patent period is too long, patients unable to afford the higher price of the patented med but who could afford the generic, will have to do without, at risk to their health.

There is nothing natural or God-given about this calculation. Likewise with property rights in general. What works for communal societies might not work for freehold societies, and vice versa. Attempts to impose the values of one on the other can have disastrous consequences. The Dawes Act of 1887 ended communal property on Indian reservations, allotting the land in freehold to separate families. Within a few decades much of the land had been lost to swindlers and sharp government practice. Collectivization campaigns in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and China in the 1950s led to famines that killed millions.

Argue about property rights all you want. But leave God—whether the God of scripture or “Nature’s God,” as Jefferson cast the Lockean concept—out of it. It’s our problem, not his.

I wrote a Medium article on this. Jefferson deliberately didn't use "property" since property can be transferred and this is not inalienable

https://link.medium.com/0VKPAHOCZzb