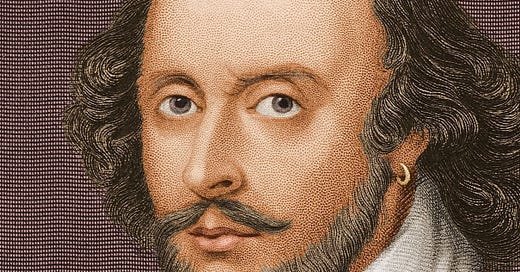

Overheard conversations have been a part of entertainment since Greek playwrights let audiences listen in on the dialogue among the characters they created. The practice continued to Shakespeare and beyond. Many plays included soliloquies, which shifted the tone. Here the soliloquists addressed the audiences, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly. But mostly the characters talked to each other, and audiences eavesdropped.

Radio allowed conversations to be broadcast to millions of listeners at once. Plays were broadcast, but radio plays with several characters challenged listeners to keep the voices and the characters straight. A conversation with two characters minimized this difficulty.

Comic duos became a radio standard. Burns and Allen, Abbott and Costello, Ozzie and Harriet, Fibber McGee and Molly and many others gabbed back and forth, and audiences tuned in. Some survived the 1950s transition to television, but more did not. Television required different traits.

The radio conversations shifted. Sports radio featured arguments between dual hosts about which team would win the Super Bowl and whether Bob Gibson could have struck out Lou Gehrig. A genre of informational radio emerged. Host doctors took calls from people with mystery ailments and diagnosed them. A classic example of information-as-entertainment was Car Talk, featuring Tom and Ray Magliozzi, which aired on National Public Radio for three decades. The Boston brothers joked, cackled and offered mechanical advice to callers.

By the time they hung up their mics and coveralls in 2012, a new technology carried the conversations. The first podcasts went out over the internet in the early 2000s. Often called audio blogs, they were the audio equivalent of the random writings people had been posting on the internet for some time. At first they were usually solos, one person speaking, often reading from a script he or she had written.

But the format that proved most popular was the conversation version. One host or sometimes two would have guests on, and they would chat. Podcasts specialized in politics, sports, business, tech, culture, cooking. There were podcasts for every taste and temperament.

Many tried to be funny. A few were. Mostly, to fans, they became comfortable. Over time, some added a video version, often posted on YouTube. Occasionally fans were surprised at seeing what the hosts they had known only by voice looked like – reviving the chestnut about having “a face for radio.”

The transition from radio to television had ended the careers of many of the radio duos. “Video Killed the Radio Star,” in the words of a hit song of that name in the late 1970s. But video didn’t kill the audio podcasts, at least not as of early 2025, when an industry estimate placed their number at four million.

One reason was that people consumed audio podcasts while doing other things: driving, exercising, cleaning house. Another reason was that conversations are made for listening, not viewing. Hearing people talk is perfectly satisfactory. Watching them talk can get boring.

If video podcasts didn’t kill the audio stars, the audio and video podcasts together went far toward killing something else: reading and writing. The internet had already displaced much of the printed word. Research that required a visit to a library in 1990 could be accomplished virtually by 2010.

But the virtual books and articles still had to be read. The rise of podcasts and videos diminished this necessity by putting the information into spoken words and into pictures. Experts continued to write books, but consumers no longer had to bother reading them. They simply listened to the podcasts on which the authors were guests.

Reading books requires effort and the readers’ full attention. Listening to podcasts is easier and requires but a fraction of the attention. To be sure, listening to a given number of words takes longer than reading them, but many people seem to be in no hurry in this area of their lives.

As an exercise, I used to have students write instructions on how to tie a shoe. It’s not easy, requiring a careful breakdown of the discrete steps. I said that writing instruction manuals was one of the hardest things for a writer to do. The exercise made my students believe me.

I no longer assign the exercise. It would serve a theoretical purpose, but the practical significance evaporated as instructional manuals were rendered obsolete by YouTube.

In important respects, podcasts are carrying us back to the days before Gutenberg. An expert – the professor – stood before a class and spoke what he knew. The students listened and thereby acquired knowledge. Then came the printing press, and for six centuries the printed word was the preferred method of transmitting knowledge. Now print is rapidly disappearing as a means of communicating information. Academic books and articles, not to mention newspapers and magazines, are read more in digital form these days than in print.

Podcasts and their kin are displacing even the digital version of writing. Most new books appear simultaneously in audio form. Major newspapers and magazines have audio versions. Interviews with experts can spare the experts the need to put their knowledge into writing.

Artificial intelligence has entered the game. Google’s NotebookLM will research a subject and present its findings in the form of an audio podcast, typically a conversation between two synthesized voices.

I for one might have my own bot distill the Notebook podcast into a transcript for reading. But I’m old school. For more and more people, the podcast’s the thing.

Shakespeare would have understood.

Podcasts are more engaging than watching someone on tv talking at times.

It is the bane of my existence that no one writes concise instructions anymore. I despise having to go to YouTube and watch 45 seconds of someone telling me what he will explain, but first giving me a whole lot of useless blather. I always look for the transcript, as I can read much faster than I can (or want to) listen. :0)