Politics and history

And me

As a history teacher, I used to be pleased when historical events came up in public debates. I thought it was encouraging that people were interested in what happened in the past. Perhaps they could learn from it.

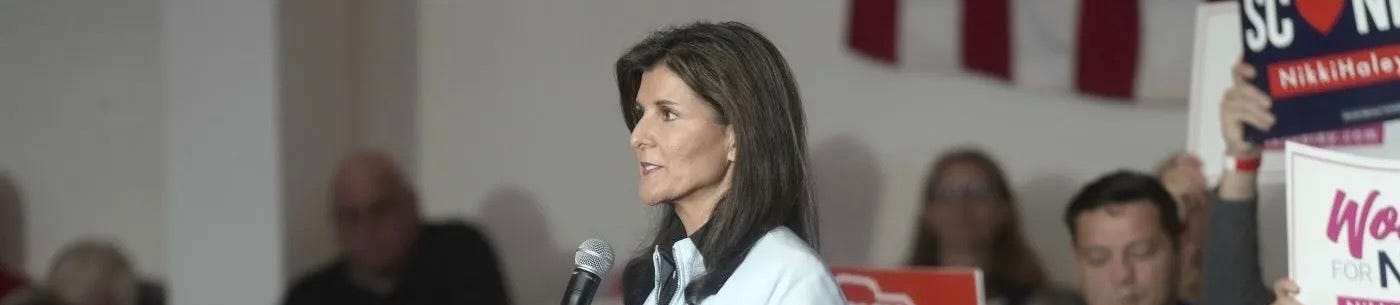

These days I generally groan. The last few years have made clear that politicians and those who engage them raise historical questions less often for edification than for weaponization. Nikki Haley's recent scuffle over slavery and the Civil War is an example. She knew perfectly well that the Civil War was about slavery; as governor of South Carolina in 2015 she signed a bill ordering the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the state capitol. But that was before she was trying to entice Donald Trump's Republican supporters to defect to her candidacy for the party's nomination for president. She later complained that it was a gotcha question. It was, which was why she should have been prepared for it.

But what should she have said? More precisely, what should she have said that couldn't be used against her? If I had been asked the question, I would have said the Civil War was about slavery and about states’ rights. I would have explained that many Americans had long believed that states had a constitutional right to secede from the Union when the states’ interests were threatened. After the election of Abraham Lincon in 1860, seven southern states concluded that their interests in slavery were threatened, and they attempted to secede. I would have said that Lincoln acknowledged the constitutional right of states to protect slavery, but he denied the right of states to secede. To stop secession—but not to end slavery—he went to war. At this point four other southern states joined the secessionists. Only long into the fighting did Lincoln add emancipation as a war aim, and then only against the rebellious states, not against the four slave states that had not seceded.

And, if I were a Republican candidate, I would have awakened the next morning to read, “Brands says Civil War about slavery.” The rest of my explanation would have been lost, because the question wasn't really about the cause of the Civil War. Rather it was about whether Nikki Haley could be cornered into saying something that could be damagingly excerpted. She dodged the corner, but not the blowback, mostly from Democrats. She subsequently acknowledged the role of slavery in the Civil War, yet it's unclear that her original answer was not the politically smart thing to say, whatever its truth value. She's not running for the Democratic nomination.

Every autumn I used to welcome the approach of Columbus Day. As various jurisdictions changed the name under which they observed the holiday— Austin, where I live, marks Indigenous Peoples Day—I would have my students conduct a mock trial of Christopher Columbus, on charges of enslavement and genocide, the crimes of which he is often accused and convicted in the court of political opinion today. It was a great opportunity for students to examine questions of contingency and inevitability in history. Is there any plausible scenario in which Europe and the Americas remained isolated from each other until the present? If not, is there any scenario in which one people with better weapons and stouter resistance to disease does not impose its will on the other? These are deep questions, and they are at the heart of the debate about Columbus.

But I eventually gave it up. I got complaints from my graduate student TAs that the discussion was insensitive to the feelings of the students of color in the room. I never received any complaints from the undergraduates themselves, but I allowed the possibility that they might be reluctant to come forward. What finally ended the trial was my increasing difficulty getting student volunteers to speak in defense of Columbus. Or for that matter to act as prosecutors. The students simply hesitated to speak out on either side of a controversial issue. It was a large class and they didn't know who they were speaking to or how their comments would be heard. Safer to say nothing at all. The trial still takes place, but I argue both sides. It's not the same.

I used to be invited to go on television and give a historian's perspective on current events. I spoke on CNN, Fox News and MSNBC, among others. But the experience grew less satisfying over time. As a commentator on CNN for Barack Obama's inauguration, I patiently waited my turn to speak, only to discover that there were no turns. If I wanted to be heard I had to shout over whoever was then talking. Fox News insisted on a pre-interview before the real thing. This is not uncommon. Producers get a sense of the areas of expertise of the guests. Fox News took it further. Their producer explained what I was expected to say. As a university professor, I was positioned as a liberal. What I told the producer I would actually say didn't fit the category envisioned for me. The invitations stopped coming from Fox News. MSNBC was more subtle. I have a cussed streak in me that causes me to question the dominant interpretation on just about any subject. The MSNBC talking heads would develop a head of progressive steam, and I would say something like, Hold on, it's more complicated than that. The hosts would simply not come back to me when it should have been my turn to speak.

I don't fault the producers of the news shows. They've figured out what audiences they want to target, and they realize that those audiences, like most people, would rather have their existing views confirmed than challenged.

And so, dear readers, I write in this space, to an audience more select, I know; more discerning, I think; and more willing to hear contrary views, I hope.

The uses and abuses of history in politics is unfortunate. It is especially so when true historians - the academics who create new historical knowledge - engage in it. I am on my way to the American Historical Association annual meeting in San Francisco. The Saturday night plenary session features Rachel Maddow, talking about "Rethinking the Far Right in American History." Perhaps I shall write it up. Maybe I can smuggle in a flask.

There are a great many reasons not to weaponize history. Among those is that using history to shape politics undermines history's greatest value. In my most humble opinion, in the fewest possible words, history's greatest value is that it teaches epistemic humility. The term has a hardcore philosophical meaning, but I mean it in a more popular sense: That history teaches that even the greatest and most consequential humans – not to mention perfectly ordinary people – were capable of astonishing errors, lapses of judgment, and moral failing, and therefore so are we all. History teaches that we should be humble rather than certain in our beliefs, for they probably won’t stand the test of time.

The problem, of course, is that partisan politics, especially as practiced today, requires precisely the opposite: Absolute confidence in one’s beliefs, however unwarranted that confidence may be. Call it epistemic arrogance. Our media, as you point out, promotes exactly that. The political use of history, therefore, corrupts history absolutely — the purpose of history is to teach epistemic humility, but partisans use history to bolster epistemic arrogance, the antithesis of its purpose. That is what I mean when I say that politics corrupts history absolutely.

(Cribbed some of this from a blog post I wrote a few months back, so I plagiarized myself a bit here. No doubt this is poor citation form!)

Great insights into how the producers of news networks work. You nailed it that viewers want their beliefs to be confirmed rather than challenged. Sad truth.