“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick,” wrote Charles Darwin to Asa Gray, an American botanist. Darwin’s queasiness was caused by the fact that his theory of evolution by natural selection couldn’t explain nonfunctional—or dysfunctional—ornaments like peacock’s tails.

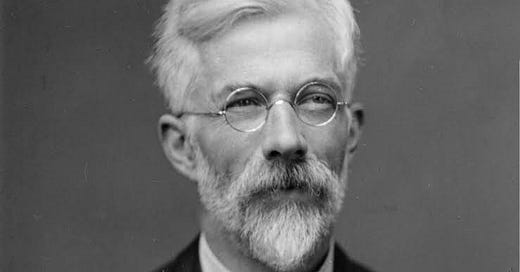

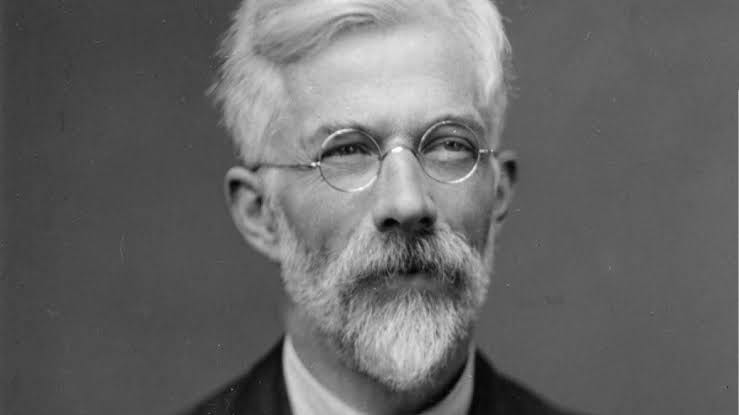

Oh, yes it could, said Ronald Fisher a few decades later. Fisher was a British biologist who knew mathematics as well. Fisher devised an explanation for the evolution of sexual dimorphism—differences in appearance between the sexes, especially including differences not directly related to reproduction. The peacock’s tail was an obvious example. Peahens have inconspicuous tails.

It was true, said Fisher, that a peacock’s tail might hinder his movement, literally weighing him down in the struggle for survival. But if peahens liked showy tails, he would mate more often than males with smaller tails, and his greater number of offspring would more than offset the awkwardness cost of the big tail. The offspring would carry his genes and have big-tailed offspring themselves.

What would make peahens like showy tails? It could be that the bright colors simply attracted their attention. But the reason didn’t matter. Once they started showing a preference for any trait, males who possessed that trait mated more often and had more male offspring with that trait. A feedback loop developed. Females who liked the trait mated more often and had more female offspring who liked the trait.

This process became known as the “Fisher runaway.” In the case of the peacock tails, it would go on until the tails got so big that not enough males escaped foxes and other predators. An equilibrium would be achieved, with tails big but not too big.

Fisher answered another question that had vexed evolutionary biologists. Why are males and females among humans so evenly balanced numerically? In any given family, boys might outnumber girls or vice versa. But in groups of any appreciable size, the family variations even out and males and females are very nearly equal in number.

What came to be called the Fisher principle described an equilibrating mechanism. Suppose at a given moment in time there are more males than females of reproductive age. The chances of females reproducing will be better than the chances of males. Their offspring will carry whatever it was that tended to make them female. More females will be born, reducing the difference in numbers between the sexes. As the difference approaches zero, the selection pressure in favor of females will decline commensurately.

In statistical fact, slightly more males than females are born. This appears to reflect the circumstance that males are more likely to die before reaching reproductive age. Young males engage in risky behavior and can get killed. Historically war has been a male monopoly. To balance out the higher male mortality, about 105 male babies are born for every 100 female babies. (This is in the absence of selective abortions, which have skewed the ratio further toward male births.)

Something comparable to the Fisher principle explains why in America there are roughly the same number of Republicans as Democrats. Suppose at a given time there are more Republicans than Democrats. Republicans win the elections but squabble over the spoils. They become disenchanted with each other. Meanwhile the Democrats have an incentive to broaden their message to attract some of the disaffected Republicans. The Democrats grow more numerous while the Republicans grow fewer. The strength of the mechanism diminishes as parity is approached.

Political traumas can knock things out of balance, in the same way that wars disrupt the balance between males and females. For a generation after World War I, females outnumbered males in Europe. For generations after the Civil War, Democrats outnumbered Republicans in the South, due to the lingering animosity against the party that crushed secession.

The equilibrating mechanism works better at the national level than in individual states, in the same way that males and females balance out across societies but not in individual families. Sometimes whole regions flip from one party to the other, until the national balance is restored. During the era of the solid Democratic South, the West Coast and much of the Northeast leaned Republican. But as the South turned red, the West and the Northeast turned blue.

The many people who grow weary of partisan politics lament that America is so divided. They seem to think that people of common sense should agree on the important issues of politics. Many imagine that we are more divided today than in the past.

They misunderstand the nature of politics. The reason we’re divided is that our politics is competitive and free. The political equivalent of the Fisher principle guarantees that we will be about equally divided. This is a good thing, as uncomfortable as it might make us at times. The alternative is a politics that is uncompetitive and unfree. It’s called dictatorship.