One picture worth a thousand lives

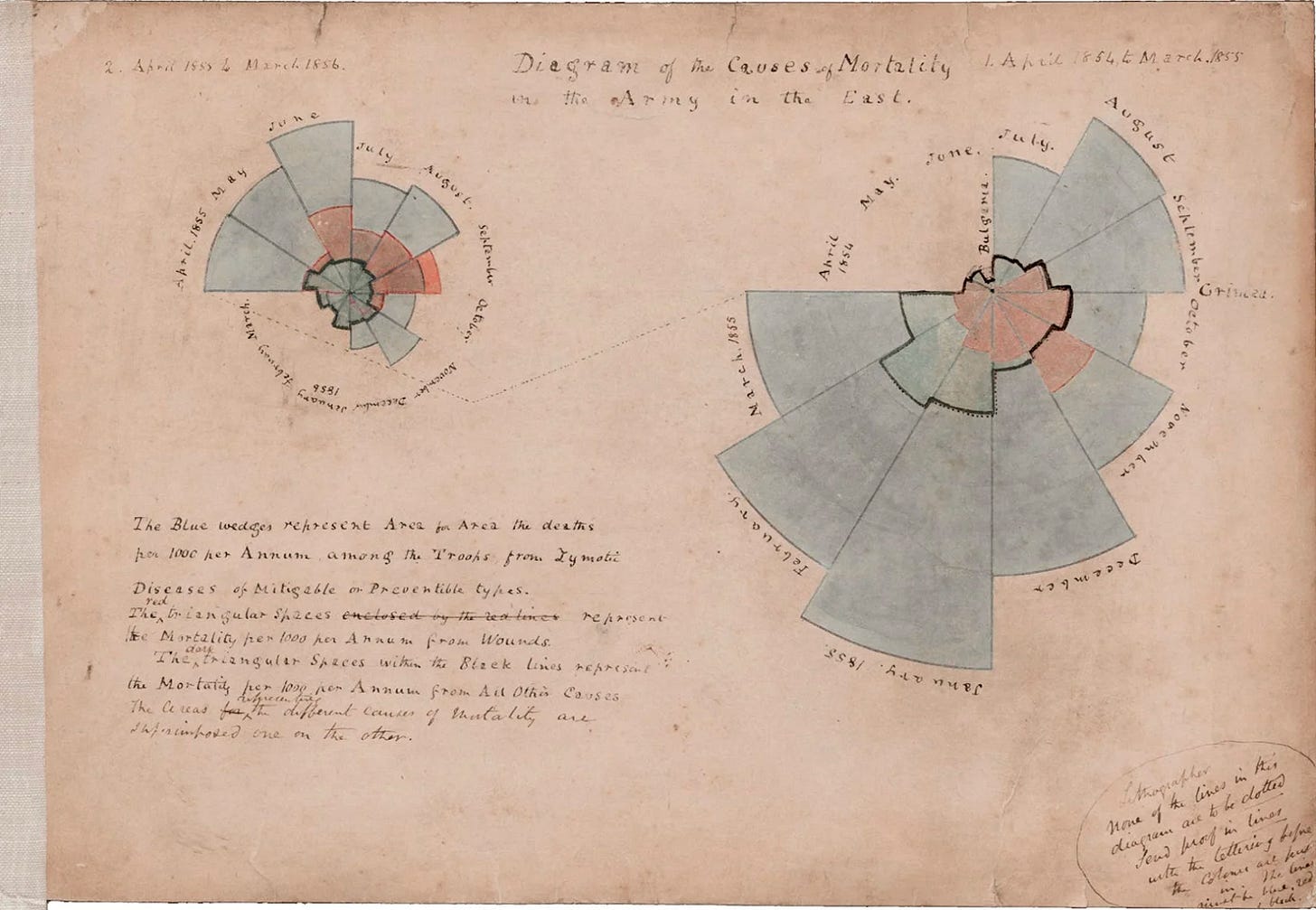

Florence Nightingale’s diagram of deaths

Florence Nightingale knew why the soldiers were dying. She just didn’t know how to convey that knowledge to the people who could make the dying stop.

Nightingale’s parents were wealthy. They traveled often from their home in England to the spas and cultural centers of continental Europe. They happened to be in Florence when their daughter was born, and they gave the child the city’s name.

As a teen she experienced what she interpreted as a summons from God to be of service to others. She chose nursing, to her parents’ dismay. With the single-mindedness that would become her trademark, she rose to the top of the profession. She cultivated politicians to increase funding for hospitals and training. When the British army went to war in Crimea in the 1850s, she went along.

She discovered what everyone involved in the care of soldiers knew in those days: that the field hospital was more lethal than the field of battle. The medical profession was only just beginning to appreciate the importance of cleanliness and sanitation in the prevention and treatment of disease. But armies are bastions of conservatism, besides resisting anything that hints of softness in the handling of soldiers.

Nightingale compiled statistics on deaths among soldiers, documenting how greatly the deaths in hospital outnumbered the deaths in battle—which was to say, how poorly the hospitals were performing on their most basic task. Yet her arrays of numbers made little impact on disdainful generals, skeptical journalists and distracted members of Parliament.

So she drew a picture.

The area in red indicated the deaths from battle wounds. The much larger area in blue showed the deaths from what Nightingale called “mitigable” disease. (The area inside the black lines recorded deaths from other causes: accidents and the like.)

The facts were no different than those Nightingale had been relating before. But her diagram, printed and distributed, made her point immediately apparent and undeniable.

The immediate results included government investigations and a flood of funding for the Nightingale Fund, for the training of nurses in the image of “The Lady with the Lamp,” as she was dubbed for illuminating the path toward better care for soldiers and others in need. Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing became a guide to the profession and a bestseller among the general public.

Deaths from disease in wartime didn’t end. More American soldiers died of yellow fever than from bullets during the Spanish-American War. But Nightingale’s efforts boosted demand for public-health reform in Britain and other countries, with consequences that played out over decades.

And her mortality diagram made her a pioneer in the field of information science—which wouldn’t acquire that moniker for another century.

From the (London) Times on the Crimean war:

She is a "ministering angel" without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.

My favorite Nightingale quote: "Better to die ten times in the surf, heralding the way to a better world, than to stand idly on the shore."