Nevermore

Or so hoped envy

“Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it. The poet was well known, personally or by reputation, in all this country; he had readers in England, and in several of the states of Continental Europe; but he had few or no friends; and the regrets for his death will be suggested principally by the consideration that in him literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars.”

The writer of these words was Rufus W. Griswold; the subject was his rival for poetic preeminence in America. Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, subscribed to the theory that the dead should be delivered to their worst enemies for appraisal, and so commissioned Griswold to write Poe’s obituary.

Griswold did justice to Poe’s troubled upbringing. Abandoned by his father at one, orphaned by his mother’s death at two, the Boston child was shipped to Richmond and the custody of a relative who died when Poe was approaching adulthood, leaving nothing to the young man. A failed stint at West Point convinced Poe to try to make his living as a writer. At his own expense—a not uncommon gamble among aspiring authors in those days—Poe published a collection of his poems, some of which, conceded Griswold, “are justly regarded as among the most wonderful exhibitions of the precocious development of genius.” The contemporary response, however, was tepid. Poe grew dispirited. “Though he wrote readily and brilliantly, his contributions to the journals attracted little attention, and his hopes of gaining a livelihood by the profession of literature were nearly ended at length in sickness, poverty and despair.”

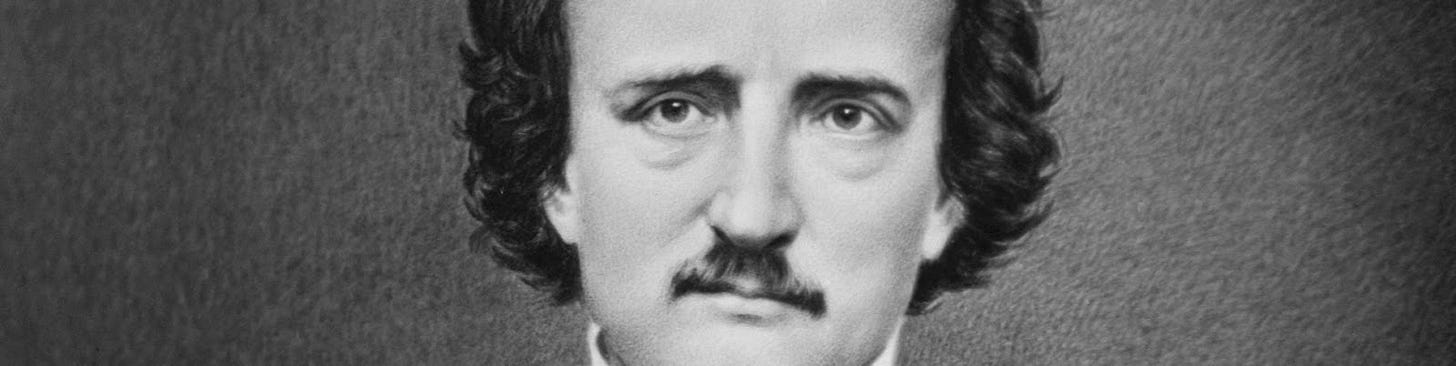

Griswold harped on Poe’s mental state. He described Poe on a typical day in Baltimore, where he had settled. “Thin, and pale even to ghastliness, his whole appearance indicated sickness and the utmost destitution. A tattered frock-coat concealed the absence of a shirt, and the ruins of boots disclosed more than the want of stockings.”

Yet the flashes of brilliance remained. “His conversation was at times almost supra-mortal in its eloquence. His voice was modulated with astonishing skill, and his large and variably expressive eyes looked reposed or shot fiery tumult into theirs who listened, while his own face glowed, or was changeless in pallor, as his imagination quickened his blood or drew it back frozen to his heart.”

By now Poe had discovered the appeal for readers of the dark and mysterious workings of the human mind and heart. “His imagery was from the worlds which no mortal can see but with the vision of genius,” Griswold wrote. “Suddenly starting from a proposition exactly and sharply defined in terms of utmost simplicity and clearness, he rejected the forms of customary logic, and by a crystalline process of accretion, built up his ocular demonstrations in forms of gloomiest and ghastliest grandeur.”

Poe’s writing reflected his soul. “He was at all times a dreamer—dwelling in ideal realms—in heaven or hell—peopled with creatures and the accidents of his brain. He walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses,” said Griswold. “He seemed, except when some fitful pursuit subjected his will and engrossed his faculties, always to bear the memory of some controlling sorrow. The remarkable poem of The Raven was probably much more nearly than has been supposed, even by those who were very intimate with him, a reflexion and an echo of his own history.” The Raven was Poe’s most famous poem, about a black bird that haunts the narrator of the poem with reminders of a loved one who has died. Griswold averred that Poe was that narrator, the raven’s “unhappy master / Whom unmerciful disaster / Followed fast and followed faster / Till his songs the burden bore— / Till the dirges of his hope, the / Melancholy burden bore / Of ‘Nevermore,’ of ‘Nevermore.’”

Griswold said nothing of the circumstances of Poe’s death, for he didn’t know them. “It was sudden,” he reported and left the matter there. He sent Poe off with a quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth on Duncan, whom he has killed: “After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well.”

Perhaps Griswold thought he had murdered Poe’s reputation. This seems to have been his intention. He couldn’t deny the quality of Poe’s work, which had been well established. So attacked Poe’s character, in ways most readers of the New York Tribune would have difficulty disputing.

For a time it appeared his assault had succeeded. The circumstances of Poe’s death proved to have been mysterious, even disgraceful. He was last seen alive in a state of severe intoxication and dressed in clothes that seemed to belong to someone else, so badly did they fit. Poe died before he became lucid enough to explain his appearance and condition.

The cause of death was not officially pronounced. The abuse of alcohol or other drugs was one possibility. Disease—influenza, cholera, syphilis–-was another. A brain tumor might have done him in. If Poe was as unhappy as Griswold asserted, overuse of alcohol or drugs might have reflected suicidal impulses. Murder couldn’t be ruled out. However it happened, Poe’s death did nothing to improve his reputation.

But the aspersions cast by Griswold backfired. Poe’s poems and especially his short stories—”The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Tell-Tale Heart” and others—conveyed themes of the macabre that perfectly suited the mad, melancholic genius Griswold made him out to be.

Poe is remembered today. Nobody’s heard of Griswold.

As a retired professor of English who loved teaching Poe in my American Literature classes, I can relate to this excellent essay. When my wife and I were visiting Guanajuato, Mexico a couple or so decades ago, we found the famous Museum of the Mummies morbidly fascinating. I thought to myself: "How Poe would have loved this museum!" Scholars are still debating the cause of Poe's death; e.g., in the current issue of _Skeptical Inquirer_, Joe Nickell dismisses all the other theories (rabies is the latest) and tries to make a case for Parkinson's.

Honestly, this characterization of Poe just makes me wish I had a time machine that allowed me to meet the guy. He is one of the few writers - in poems like Annabel Lee in particular - capable of making the English language sound as lyrical as French or Italian.