Never a good war or a bad peace

Maybe, Ben. But maybe not

In September 1783, representatives of the governments of Great Britain and the United States signed the peace treaty that officially terminated the American Revolutionary War. The heart of the agreement was contained in Article 1, in which Britain acknowledged the independent sovereignty of the United States.

Article 2 defined the geographical boundaries of the United States. Article 3 dealt with fishing rights.

Article 4, on debts, said that creditors on either side should meet with “no lawful impediment” to the recovery of what was owed them by debtors on the other.

Article 5 said that Congress would “earnestly recommend it to the legislatures of the respective states” that property taken from Loyalists be returned or paid for.

Article 6 said that prisoners would be freed.

Article 7 promised that British troops would be withdrawn from American soil “without causing any destruction or carrying away any Negroes or other property of the American inhabitants.”

Article 8 treated navigation on the Mississippi River, America's new western boundary. Article 9 said that each side would return territory taken from the other during the war. Article 10, the last, called for ratification of the treaty within six months.

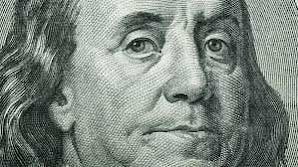

Benjamin Franklin, chief negotiator on the American side, greeted the termination of the war with relief. “There never was a good war or a bad peace, he said.

Yet some peaces were better than others. Franklin recognized the wiggle room in the terms of the Paris accord—because he had deliberately put it there. Articles 4 and 5 were patent invitations to Americans not to pay debts or return seized property. The former merely said debt collection should not be outlawed, and the latter that Congress would recommend the return of property.

Article 7 posed a particular problem for the British, who had promised freedom to the slaves of rebel masters who crossed British lines and fought on behalf of Britain. Thousands took up the offer. Article 7 indicated that these former slaves would be left behind upon the British evacuation.

It was these Black Loyalists, as they were called, whose predicament caused the treaty to unravel even before it was ratified. British commanders in New York, where most of the British troops and Loyalists, including the Black Loyalists, were concentrated at the war’s end, refused to renege on the promise of freedom to the former slaves. Ignoring the treaty, they piled the Black Loyalists onto the ships that carried the troops and the other Loyalists away from America. Some went to Canada, others to the British West Indies, and a few to Britain.

American officials at once complained on behalf of the slaveholders deprived of their legal property. They reasoned, as well, that if the United States didn't insist on its rights in this treaty, it would lose credibility in the eyes of the world.

The British rejected the complaints. The states were showing no inclination to return Loyalist property, and they were passing laws forbidding collection of British debts. If the Americans weren't honoring their end of the bargain, the British said, then neither would they.

What particularly rankled Americans was the British refusal to give up forts on American soil near the Great Lakes. The forts were easier to supply from Canada than they were to attack from America, and they weren't important enough to fight another war over, so soon after the last. But it stung American pride to know that the British flag waved over American territory.

There was a security angle as well. And a commercial one. The British forts provided weapons to Indian tribes unhappy about encroaching American settlements. And the forts drew trade in furs to British companies rather than American ones.

For a decade after the treaty, the British held on to the forts. A new treaty, negotiated in 1794 by John Jay on the American side, was required to resolve the issue. By then the forts were the least of the problems vexing Anglo-American relations. More embittering were British seizures of American ships and sailors as part of Britain’s war with France. Resolving this problem required not another treaty but another war, of 1812.

I recently finished "Disunion Among Ourselves : The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution" by Eli Merritt. It was fascinating to learn how much fishing rights off Newfoundland was to New England colonies and access to the Mississippi was to the southern colonies. Both issues threatened the war alliance.

Per Merritt's book, even after the war, there were several issues which threatened to break the nascent USA into two or three smaller confederations!

History classes in K-12 certainly don't delve that deeply, instead relying on our core revolutionary myths.

Years ago I read "A Few Bloody Noses" by English historian Robert Harvey. If I recall, one element not mentioned in OUR history books was the treaties the British had with the native Americans west of the Appalachian mountains which promised to keep European colonists east of that line, but which Americans, eager for land, kept breaking. The colonists resented the British for keeping them coastal.

Many of the Black Loyalists ended up settling in the province of Nova Scotia and particularly the city of Halifax, which today remain among the places in Canada with the highest Black populations.