Moses, meet Darwin

Decisions, decisions

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth, says the book of Genesis, the first guide to management practice. The book was written by Moses and his public relations team, and it was the authoritative account of what came to be called the top-down style of leadership. Abraham & Sons, the firm Moses describes, has had a long run, although Moses' time as CEO was marked by indecision and delay, including an inexplicable forty-year sojourn in the Sinai desert.

For three millennia after the book was written, the top-down style had the field of management theory to itself. Things happened in the business world, and the world beyond, because somebody made decisions to make them happen. The human imagination couldn’t fathom any other approach.

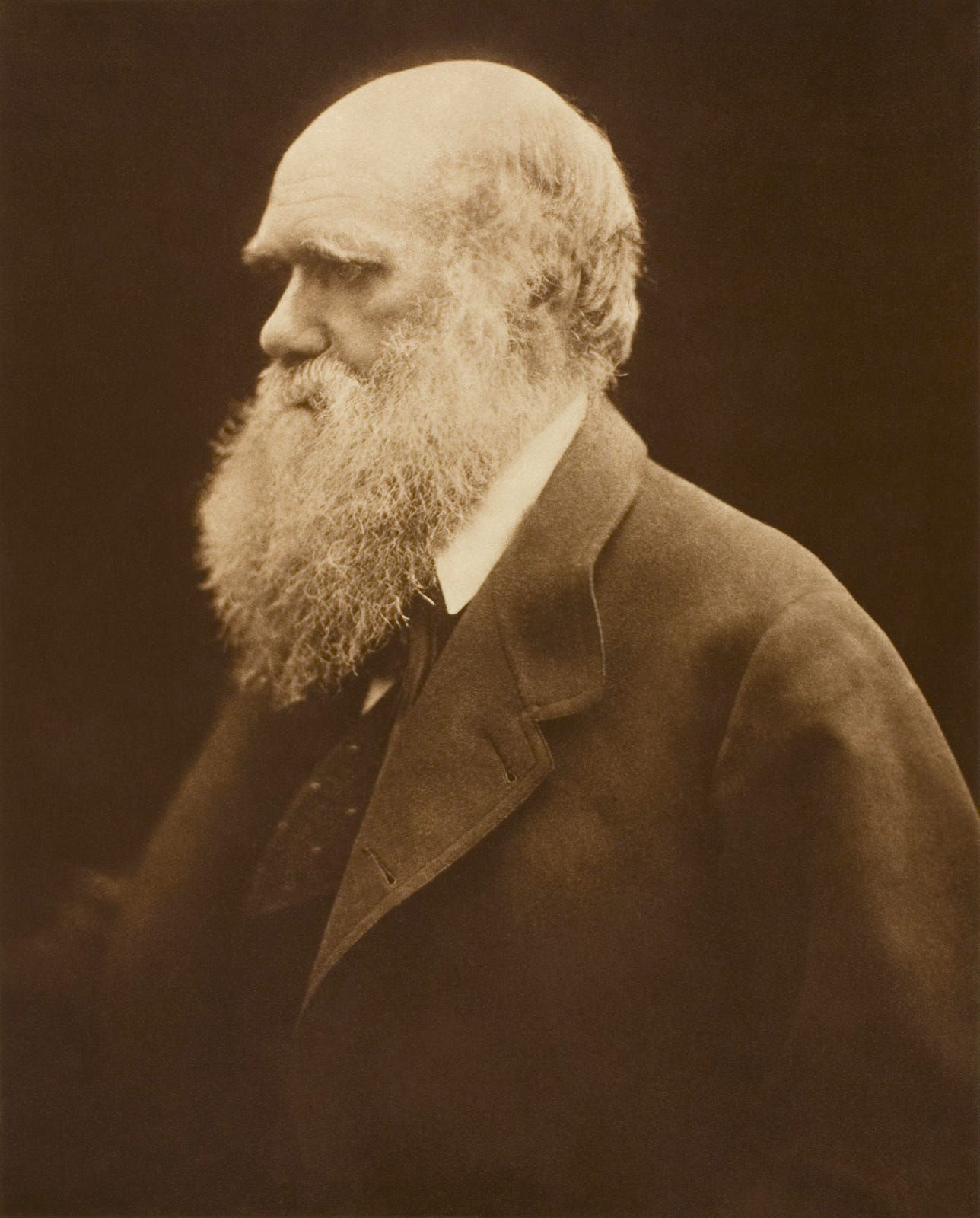

Then, in the nineteenth century of the common era, Charles Darwin proposed a different model. The Englishman saw change occurring from the bottom up. Darwin's specialty was the life sciences, and he described the extant flora and fauna as the product of changes not dictated by any superintending intelligence but accomplished by actions and influences at the level of the individual organism and its kin.

These two approaches to decision and change—the Mosaic and the Darwinian—persist until today. They characterize businesses, governments and societies.

The governments that embody the Mosaic approach in purest form are the autocracies. Monarchies, a subset of autocracy, long justified their authority as coming from God. Starting in the twentieth century, ideology has been a more prominent pillar of autocratic authority. Autocracies presume to know best for their subjects and they govern on this presumption.

Yet all governments, simply because they are governments, manifest Mosaic traits. However, decisions are made, they are imbued and enforced with coercive authority. If you break a law in China, where the Communist party rules, you go to jail. If you break a law in the United States, a pluralist democracy, you go to jail. Americans have more freedom to participate in the passage of laws, and more freedom to protest laws they don't like, but they have no more freedom to violate the laws. In China, everyone is subject to the will of the ruling party; in America, the minority on any given issue is subject to the authority of the majority.

This is at once a strength and a weakness of the Mosaic approach. Lines of authority are clear, but substantial groups are at the mercy of others.

A second problem with the Mosaic approach is that it supposes sufficient knowledge and wisdom in government to make good laws. This wasn’t an issue with the archetype: God was all-knowing and all-wise when He created the heavens and the earth. But His human successors fall short. And they fall shorter the larger the entities they try to govern. A village chief or a town manager can know everyone he or she governs, but a commissar or a bureaucrat in a country of fifteen hundred million has no such chance. “Heaven is high and the emperor is far away,” says a traditional Chinese proverb. The current emperor is farther away than ever.

The Darwinian approach lacks the decisiveness and clarity of the Mosaic even as it avoids the Mosaic’s overconfidence and reliance on compulsion. Darwin’s breakthrough was to realize that change in plants and animals results not from deliberate decisions on high but from the accidental interplay of environment and variations among individual organisms. Darwin’s successors would discover that the drivers of evolution are genes, tiny components that compete in a never ending tournament. Genes are ignorant but “selfish,” to use Richard Dawkins’ descriptor. They defeat rival genes by producing offspring better suited to their environment.

In the late twentieth century the Darwinian approach would inform the study of “emergent properties”—characteristics that result from the interaction of individual entities, beyond characteristics of the individuals themselves. To humans, ants in a colony under attack can appear brave and self-sacrificing, when the individual ants are neither. They are simply following the instructions of their genes, which unknowingly but effectively have figured out how to defend the colony.

The Darwinian approach is inefficient compared with the Mosaic. Should conditions change, the Darwinians require generations to adapt, whereas the Mosaics can shift strategy at once. This is why democracies often mimic autocracies in time of war or other emergency. Franklin Roosevelt wielded almost as much power in America during World War II as Joseph Stalin did in the Soviet Union.

But the Darwinian approach requires no external enforcement. Individuals pursue their own self-interest and—voila!—the collective thrives. Or at least it achieves an outcome that can’t easily be bettered under existing circumstances. If it could be bettered, it would have been.

The Darwinian approach works best in economics, where it is essentially market capitalism. The Mosaic approach—a command system—is overwhelmed by the informational needs of any large economy. By the time the commissars get the message that bread is short in the provinces, and this message is converted into signals to bakeries to increase hiring and expand production, the provincials are on the brink of starvation or revolt. In a Darwinian system the signals are interpreted nearer the source and the response is more timely. Here it acts like the human system of reflexes, where a stimulus—the pain of touching a hot burner, for instance—can produce a response from the spinal cord even before the pain signal reaches the more distant brain.

The self-interest of individuals guides the decisions of the Darwinian economy. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest,” wrote Adam Smith, a Darwinian before Darwin. No central authority coordinated their actions; rather the separate interests summed to an “invisible hand” that produced positive general outcomes—beef and beer and bread for the hungry, thirsty populace.

Many modern societies employ an approximation of the Darwinian bottom-up mode of decision-making in economics. All societies use a version of the Mosaic method in politics—which is to say in government. It wasn’t always so. Many of the indigenous peoples of North America made their tribal decisions by consensus and voluntarism. When a leader like Geronimo or Crazy Horse wanted to launch a raid on another tribe or on white settlers, he would make his case and set out with only those who chose to join him. There was no equivalent of conscription. This was one reason Indian resistance to white encroachment finally failed. White officers gave orders and shot soldiers who disobeyed; Indian leaders did not.

It’s no coincidence that the power of the American government has ratcheted up with each war the country has fought. The Revolutionary War produced the first national government; the Civil War bludgeoned the states into submission; World War I nationalized American heavy industry for the duration; World War II created the national security state—what Dwight Eisenhower decried as the “military-industrial complex.” Nowadays it rarely occurs to most Americans that anything important can be accomplished without government participation, which means government compulsion. Even the economy grows less Darwinian, as Mosaic-minded regulators attempt to enforce good behavior on corporate entities.

It’s really not surprising. There’s comfort in the familiar. The Mosaic approach has been with us since . . . well, the beginning.

Darwin never recanted his scientific views. That is a tattered old fabrication.

While I for years have read Richard Dawkins for his world view perspectives, I have also for years read Prof. Brands, initially for American historical perspectives, but now for Big History perspectives. And today for business school management analysis and political science insight, with some theology thrown in.

Truth be told, Brands is easier to read than Dawkins and more pleasing to my eye and ear. This is important since our brains have evolved in such a way that stories and the construction of stories therein are essential to our ability to store and recall facts for future action and to pass on to others and later generations learning from experience in a way that is faster and more broadly disseminated than genetic mutations can and may ever will. Others have written on this as an explanation for the rise of human civilization and our specie’s dominance over others. And Brands is the better story teller.

This essay is one of my favorites and its reading a refreshing way to start the day. (But I acknowledge that some of my refreshment this morning may be from the cool front that has come through.)